Nick Hunn previously wrote Essentials of Short-Range Wireless (2010) – where he addressed Bluetooth Classic, Wi-Fi, Zigbee, and Bluetooth low energy (LE). He has been involved with Bluetooth since its inception and has helped author most of the major Bluetooth requirements documents, including those for Bluetooth Low Energy and LE Audio. Since 2013 he has chaired the Bluetooth Hearing Aid working group, which developed the concept of Bluetooth LE Audio and he has participated in writing all of the Bluetooth LE Audio specifications. As often mentioned (and I know I did a few times), in 2014, Nick Hunn coined the word "Hearables."

Before I discuss his book further, I need to address the topic of compression in audio. Data compression that is (not audio dynamics compression), and more specifically for Bluetooth wireless audio transmission. The process of reducing the size of a data file is often referred to as data compression - and Nick Hunn uses the term in his book. For those who like to discuss the terminology (and I'll proudly quote Wikipedia here), "in signal processing, data compression, source coding, or bit-rate reduction is the process of encoding information using fewer bits than the original representation." Any particular compression is either lossy or lossless. Typically, a device that performs data compression is referred to as an encoder, and one that performs the reversal of the process (decompression) is a decoder - hence, the use of the term "codec" is a blend of (en)coder/decoder.

Also important, let's recap on the "LE Audio, the Next Generation of Bluetooth Audio" announcement by the Bluetooth Special Interest Group (SIG), which I reported directly from the show floor at CES 2020. This was an important moment for the audio industry, given that the next generation of Bluetooth audio was in the works for quite some time. The Bluetooth SIG announcement confirmed that, "Not only will LE Audio enhance Bluetooth audio performance, it will add support for hearing aids and enable Audio Sharing, an entirely new use case that is poised to once again transform the way we experience audio and connect with the world around us."

Two years after this announcement, even though the essential technology pieces are starting to fall into place, we don't know very clearly what will happen with the adoption of Bluetooth LE Audio. Manufacturers committed to its implementation (e.g., hearing-aid manufacturers) have not announced any specific product launches for the immediate future (2022). Consumer electronic companies, much less. We assume all are refraining from disclosing their plans, until we see wide support from source devices (smartphones).

Two years later, what we now have is a book by Nick Hunn to clarify all the doubts about LE Audio. Somehow, I have a feeling that the industry momentum has been partially lost.

But even more excitement seems to be generated by potential applications for LC3plus (ETSI TS 103 634), enabling 24-bit audio transmission at 96kHz sampling, with as little as 2.5ms delay. Bang , targeting high-resolution wireless audio streaming applications.

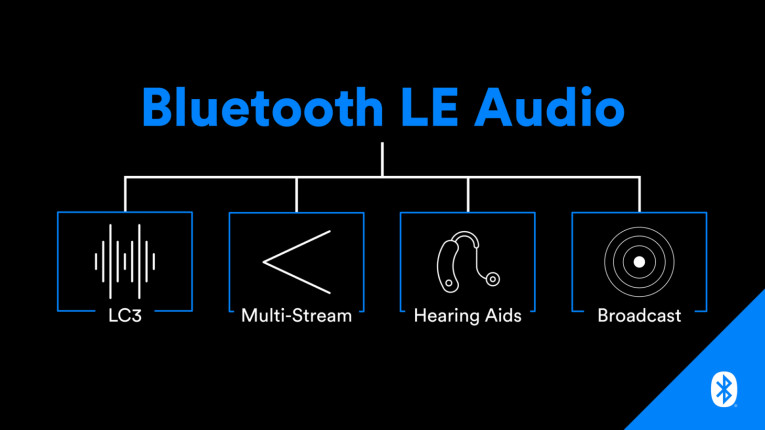

At the time of the original Bluetooth LE Audio announcement in 2020, the big selling points were:

- Multi-Stream Audio to enable the transmission of multiple, independent, synchronized audio streams between an audio source device, such as a smartphone, and one or more audio sink devices (e.g., true wireless stereo earbuds).

- More efficient, low power, Bluetooth Hearing Aids.

- Broadcast Audio - one or more audio streams to an unlimited number of audio sink devices.

- Audio Sharing - personal or location-based.

We have all been waiting for the complete Bluetooth specifications that define LE Audio to be released (www.bluetooth.com/le-audio) - which has been happening gradually - but has yet to be finalized.

The new book from Nick Hunn doesn't provide any new information about those possibilities and instead basically offers a consolidated overview of the work that occurred prior to the January 2020 announcement of Bluetooth LE Audio, and guides the reader through the specifications.

In the introduction, Hunn makes it clear that the Bluetooth LE Audio process started in 2013 for and by the hearing aid industry. And his inside perspective of what led to the updated LE Audio specifications is basically what makes this an important book to read, because it helps audio industry professionals in general to understand the thought process.

As mentioned, Hunn does discuss "data compression" throughout the book. Specifically, discussing the trade-offs of quality and latency he mentions the following: "During the Bluetooth LE Audio development, it became apparent that the current Bluetooth codecs would struggle to meet the requirements. Not only were they limited in their quality and latency trade-offs, but SBC is not as efficient as earbud and hearing aid designers would like. (...) To address these limitations, the Bluetooth SIG went on a codec hunt, which resulted in the inclusion of LC3."

And he adds: "Bluetooth LE Audio allows manufacturers to use other codecs, but LC3 is mandatory for all devices. The reason for this is to ensure interoperability, as every Audio Source and every Audio Sink has to support it. The full specification for the codec is published and falls under the Bluetooth RANDZ35 license, so anybody can write their own implementation and incorporate it into their Bluetooth product, as long as those products pass the Bluetooth Qualification process. Given its quality, that’s a powerful incentive to use it."

Of course, for everyone who thinks that Bluetooth is a detriment to audio quality, this might be surprising - and likely demoralizing - because it doesn't hint at the slightest intention to improve things away from those early defined goals. As an example, I noted the part that mentions the "high-quality" sampling frequency limit if 48kHz, and the compromise in LC3 frame sampling (specific to Bluetooth LE Audio) to support "legacy 44.1kHz sampling" (when are we going to get rid of this CD-legacy curse?).

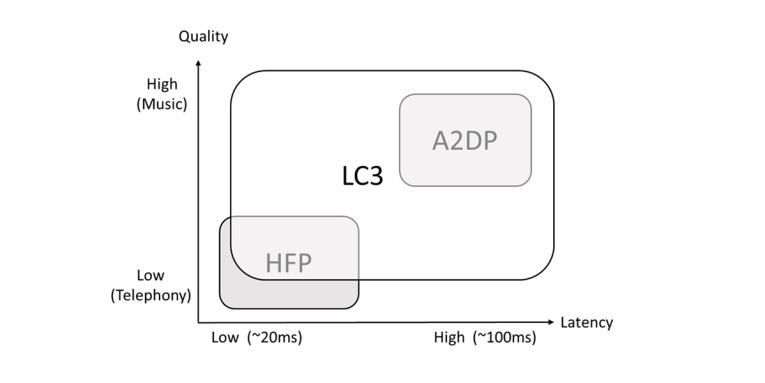

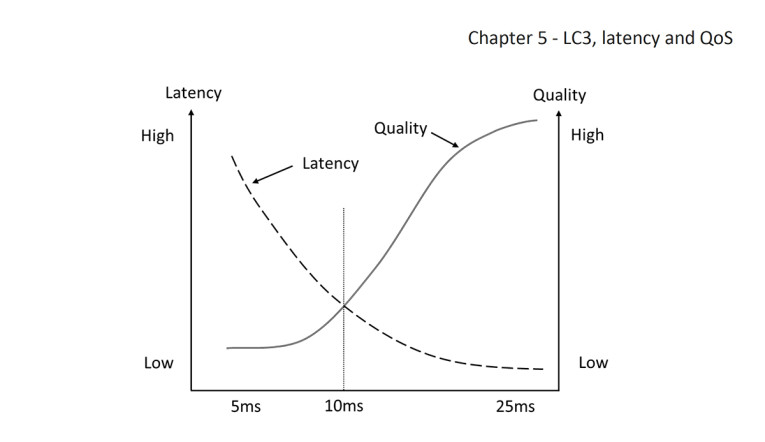

Figure 5.2 from the book, illustrating the sweet spot for audio codec frame size, juggling latency and Quality of Service.

So, if you feel you are part of the "small group of users," you might feel uncomfortable by reading this: "What is important is that audio application designers understand that there are compromises in designing a wireless audio experience and that some QoS choices may exclude the development of new use cases. Some sections of the audio industry will jump onto the higher quality that LC3 offers and promote the highest sampling rates, despite the fact that limitations in reproduction and the listening environment will probably mean that few, if any listeners will appreciate them."

So there. Without underrating any of the merits of Bluetooth LE Audio as a better option for replacement of what we currently have - which I fully support - it is painfully obvious that Bluetooth LE Audio targets a lower-common denominator that could meet the standard, without looking at the fundamental question of updating the standard itself.

A lot has happened since the requirements for the specifications were determined. And it's highly likely that there will be other audio wireless implementation alternatives coming to market very soon - proprietary, or based on existing standard technologies - to meet the demands from that "small group of users." Apple Music and other music streaming services are committed to lossless streaming, and everyone is reevaluating the "pipe" bandwith/latency trade-offs for wireless systems. More importantly, as Qualcomm knows, the "small group of users" is not that small.

Looking specifically at the topics that audioXpress readers most frequently search for in our published content, this book hardly addresses any of the terms. This book doesn't contain a single reference to "high-resolution audio" or "uncompressed"; it contains one single quote for the "lossless" term in the discussion about quality; it includes three mentions of the word "spatial" - only two of which refer to "immersive"; while 3D sound is quoted only once.

Figure 5.4 from the book, showing the efficiency gains from using the new LC3 codec compared with the Bluetooth Classic profiles. When mentioning existing optional codecs for Bluetooth audio, Nick Hunn describes "AAC" simply as the codec "used by Apple in most of their Bluetooth products,” and aptX as an earlier attempt to solve Bluetooth audio limitations very specifically for streaming stereo to two independent earbuds.

And of course, most of it is intended to explain the new and exciting possibilities with Broadcast Audio Streams and Broadcast for all, Audio Sharing, as well as the multiple control mechanisms. Which will be a completely new experiment for consumers - so no one knows very well what to expect. As Hunn writes in Chapter 12, "The whole point of developing Bluetooth LE Audio was to support new audio applications, not just to produce a slightly lower power alternative to the existing Bluetooth Classic Audio profiles. Part of that was driven by the need to catch up with proprietary extensions, particularly for True Wireless Stereo."

And he adds earlier in Section 1.1: "The speed of development surrounding the introduction of earbuds, and Apple’s Airpods in particular, has been amazing. We have seen many new companies developing Bluetooth audio chips, advances in miniature audio transducers and MEMS microphones, along with a massive growth in the number of companies providing advanced audio algorithms to enable features like active noise cancellation, echo cancellation, spatial sound and frequency balancing."

After reading this, I was left with a feeling of a disconnect precisely with the companies he mentions in that passage - which essentially will be the ones to determine the future of Bluetooth LE Audio and beyond.

This article was originally published in The Audio Voice newsletter (#360), January 20, 2021.