I have already described phase modulation, or as I called it in my previous article (audioXpress, October 2024), the “Doppler Effect.” Briefly, Doppler distortions generate non-harmonic spectral lines, which are independent from the listening distance and need to be eliminated for a good listening experience. Non-linear amplitude modulation (NLAM) generates harmonic and intermodulation spectral lines that decrease with listening distance.

Background

Perfect sound reproduction requires a system able to translate the sound pressure of a source into a usually storable signal (e.g., an electrical audio signal) and translates that signal back into sound pressure without modification. To do that, system theory [1] tells us that one needs first a linear and second a time invariant system.

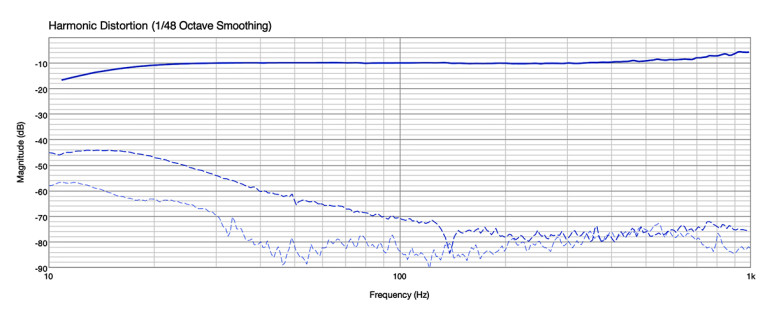

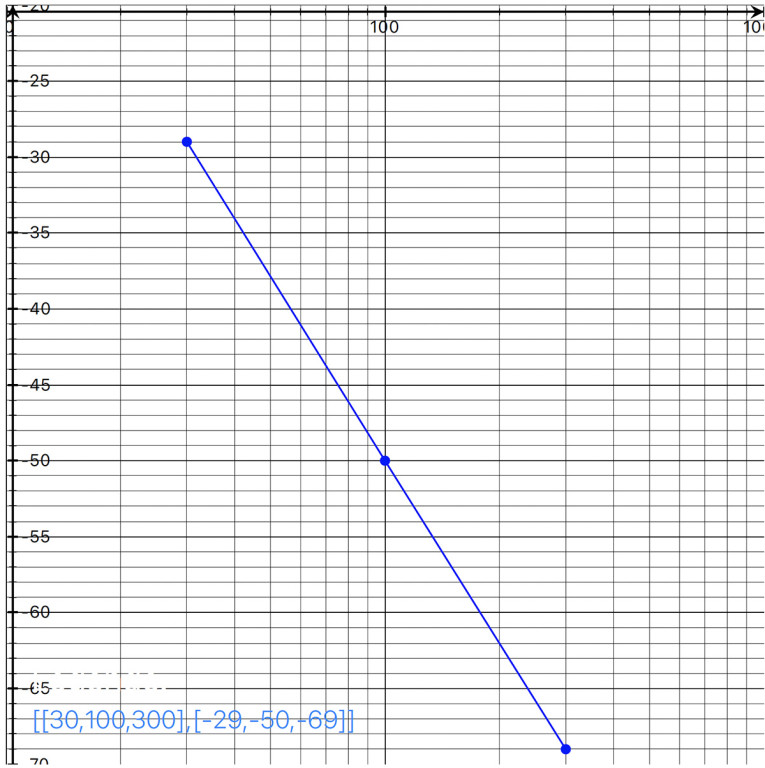

One can fulfill the first requirement on linearity using a loudspeaker, for example, with acceleration feedback (AFB), as described in a prior audioXpress article [2]. By this technique, the linearity of a loudspeaker can be improved such that harmonic and intermodulation distortions are reduced to below -60dB (0.1%) relative to the fundamental frequency. Figure 1 shows the sound pressure level (SPL) frequency response of an acceleration-controlled loudspeaker together with the harmonic distortions k2 and k3.

distortion k2, and lower dashed line=harmonic distortion k3. Measurement parameters: AudioChiemgau ModeCompensator [6], Sweep time is 10 seconds, Time window is 10 seconds, frequency resolution is 0.1Hz. The stimulus signal is high-pass filtered at 15Hz (-3dB) to limit the membrane amplitudes at frequencies below 15Hz.

Obviously, with acceleration control technology, a sufficient linear system can be achieved with moderate effort. So, the first mentioned requirement on linearity can be sufficiently fulfilled. Above 100Hz, the harmonic distortions are below -60dB (0.1 %). However, at lower frequencies especially the harmonic k2 is rising toward lower frequencies. The reason lies inter alia in the violation of the second above-mentioned requirement on time invariance.

While recording the sound, the membrane of a condenser microphone moves with an amplitude of about 1μm at low frequencies (20Hz) and high SPLs (100dB). The same is valid for the tympanic membrane of the human ear.

However, during play back a loudspeaker membrane may move up to 1cm amplitude to reproduce the recorded sound with the above-mentioned frequency and SPL.

To put it in simple terms: We record at an almost fixed location in the sound space, but we reproduce at a variable location in the sound space. This 1 to 10000 ratio of the membrane amplitudes between recording and reproduction leads to well audible distortions, even for a perfect linear loudspeaker.

The Generation of the Non-Linear Amplitude Modulation (NLAM)

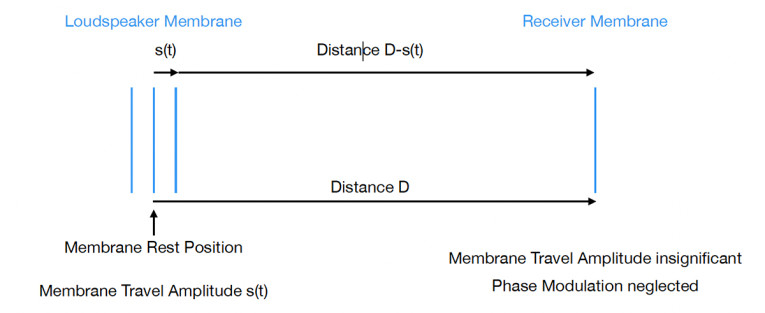

Figure 2 visualizes the generation of the NLAM. The loudspeaker membrane travels with the amplitude s during reproduction of the sound. As a consequence the distance D between the rest position and the receiver (ear, microphone) varies by the travel amplitude s.

Because of the inverse proportional law [3] between sound pressure and distance, the sound pressure varies at the receiver inversely to the actual distance.

Thought Experiment: One can imagine a high note being played back by the loudspeaker. Simultaneously a low note with considerable membrane travel amplitude is being played back. The location at which the high note is generated travels with the membrane position back and forth. Because of the inverse proportional law between sound pressure and distance, the high note is “louder” (i.e., has a higher sound pressure) when the membrane is closer to the receiver and vice versa. This principle is a general one and is valid for any note or frequency, even, when only one frequency is played back. The amplitude of the sound pressure at the receiver is modulated by the factor:

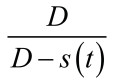

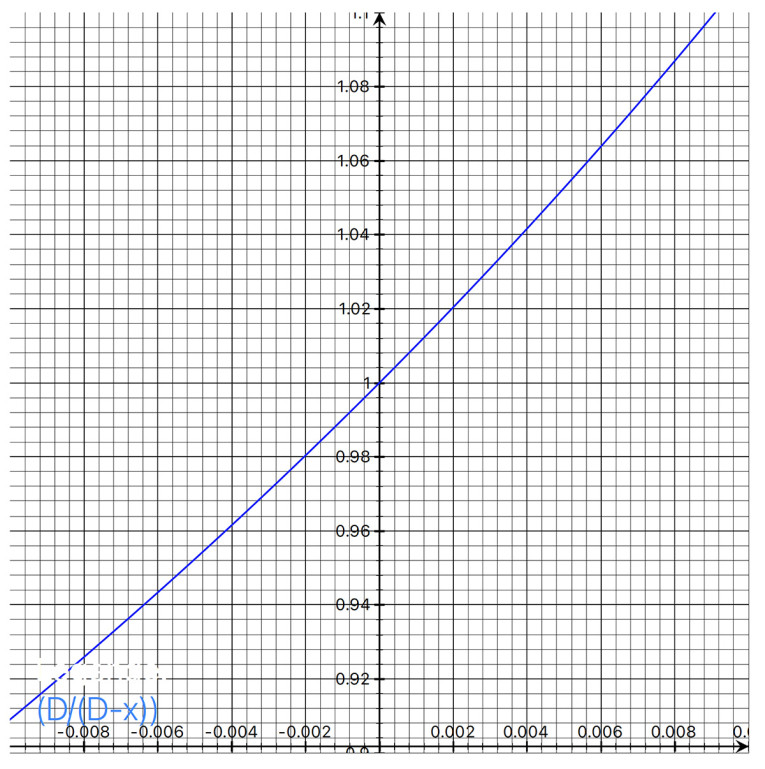

With the distance D between the loudspeaker membrane rest position and the receiver. The loudspeaker membrane moves as function of the time by s(t). The modulating factor, shown in Equation 1, is a nonlinear function of time as an inspection of Figure 3 reveals. That is the reason one can talk about NLAM of the sound pressure at the receiver.

Consideration in the Time and Frequency Domain

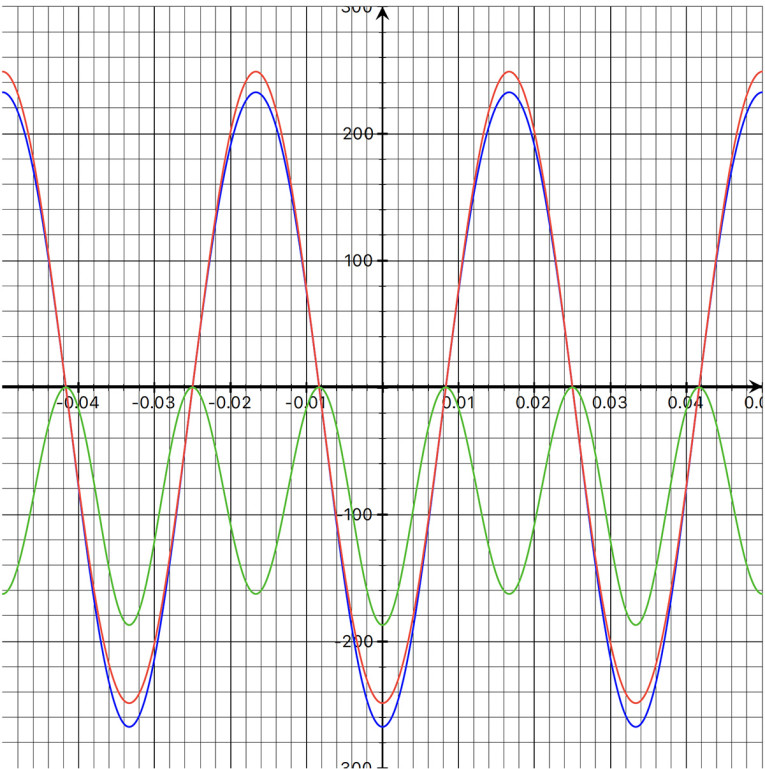

The time domain plot in Figure 4 shows in blue the sound pressure at the receiver considering the inverse proportional law. The difference between the ideal sound pressure (red) generated by an acoustically steady membrane (an extremely large area membrane with negligible membrane travel amplitude) and the real sound pressure considering the inverse proportional law is shown in green (10 times magnified) at the receiver. The distance D is 10cm, for the example.

This difference is always negative. Its minimum is at the positive and negative maxima of the waveform and zero at the zero crossings of the waveform. This difference is identified as the NLAM, generated by the moving loudspeaker membrane. From Figure 4, it is obvious that the resulting main difference frequency is twice the fundamental frequency (i.e., a second harmonic is generated).

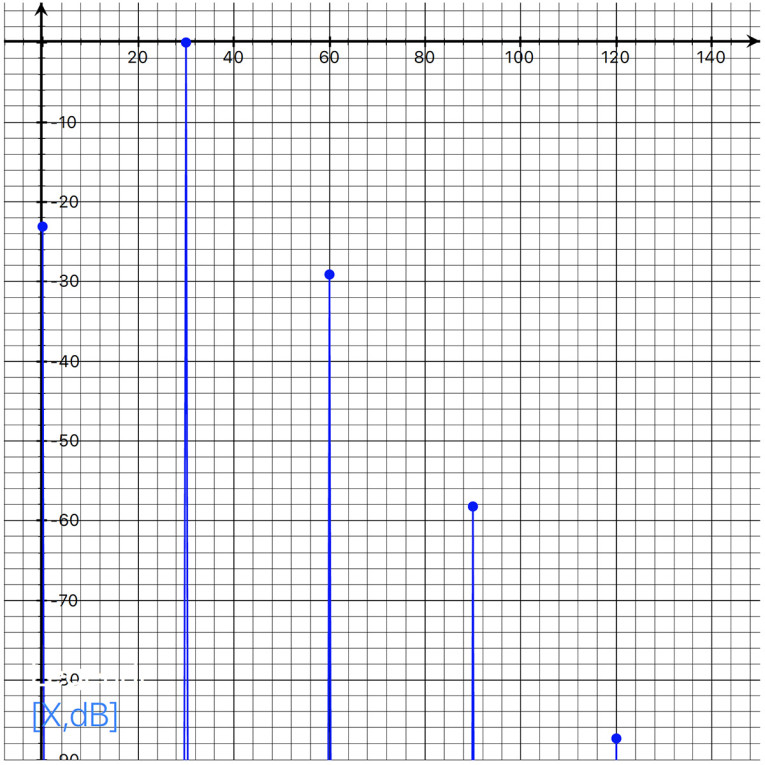

In the frequency domain, the Fourier transformation of the waveform at the receiver in Figure 5 shows that there are further harmonic frequencies, however with smaller amplitudes. The second harmonic for this example is 29dB (3.5%) below the fundamental frequency and the third harmonic is about 58dB below the fundamental frequency amplitude. There is a DC component generated too, which makes the compensation of that distortion difficult, as the compensation function is also generating a DC component. We will come back later to this.

Consequences for the Near-Field Measurement of Loudspeakers

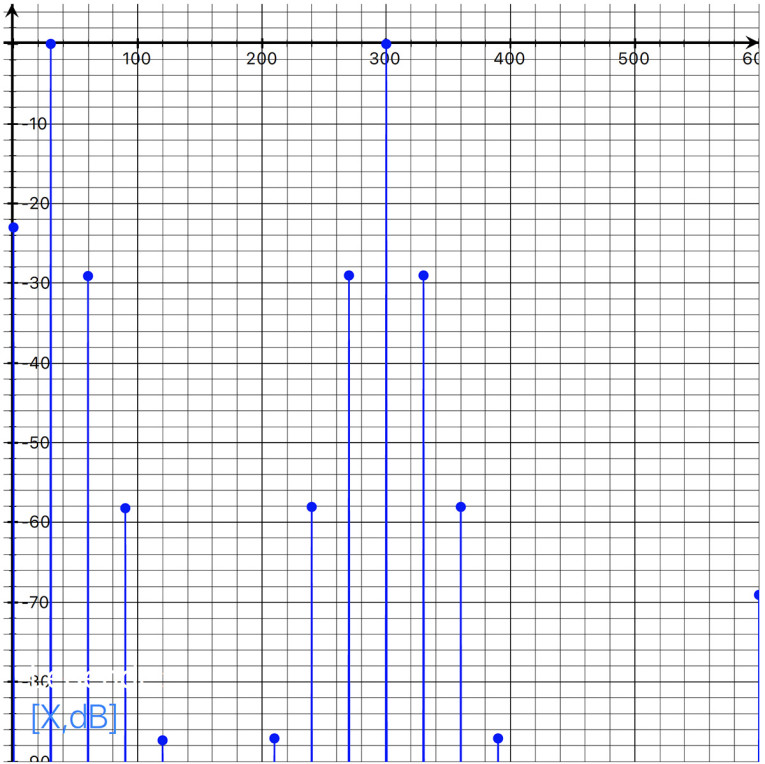

We see that the moving loudspeaker membrane creates, because of the inverse proportional law, a non-linearity for the SPL at the receiver, which results in the generation of harmonic frequency components and intermodulation in case more frequencies are involved. Figure 6 shows the resulting spectrum for two frequencies of 30Hz and 300Hz at the same SPL.

The spectrum is quickly filled with intermodulation products when there are more frequencies present. The calculation of the NLAM dominating second harmonic vs. frequency in Figure 7 shows a drop by 12dB per frequency octave, which corresponds to the drop of the membrane amplitude as function of the frequency at constant SPL. A variation of the microphone distance, or the membrane travel amplitude results in graphs parallel shifted along the Y-axis.

From these results the following general rules for the effects of the NLAM can be derived:

- The NLAM (i.e., the generated harmonic spectral lines) are approximately proportional to the quotient of membrane travel amplitude and the distance but the exact dependency is non-linear (as shown in Figure 2).

- The NLAM is independent from the frequency but generates intermodulation products between different frequencies. Intermodulation products are non-harmonic and very disturbing to a good listening experience.

- The NLAM decreases with growing distance from the transmitter/loudspeaker by 6dB per doubling of the distance and can usually be neglected above 3m even for loudspeakers with small diameter woofers with significant membrane travel amplitudes.

- For distortion measurements, the NLAM needs to be carefully considered, especially for near-field measurements.

Consequences for Listening

The significant relationship by a factor of approximately 10000 of the membrane travel amplitudes between recording and play back leads to a non-linearity, generating inter alia harmonic and intermodulation distortions. At deep notes and high SPL these distortions can easily dominate the distortions generated by a good loudspeaker chassis at relatively small listening distances. This may, for example, be the case for monitor rooms. Consequently, one must not go below a minimum listening distance (e.g., 3m) to achieve a fairly undistorted sound experience.

Elimination of the NLAM

As the generation of the NLAM results in a multiplication of the sound pressure by the factor (D-s(t)), it can be compensated/eliminated, however exactly only for a defined listening distance D. The elimination is based on an amplitude modulator (e.g., in a digital audio processor [5]) using the membrane position as control signal. By modulating (multiplying) the audio signal with the inverse NLAM factor (1-s(t)/D), it is possible to compensate (pre-distort and such eliminate) the NLAM for a defined distance D. This requires the exact knowledge of the membrane position s(t) at any point in time, which can be calculated as double integral of the audio signal versus time. Using an acceleration-controlled chassis, which has a negligible phase of its sound pressure transfer function, allows a nearly perfect cancellation of the NLAM.

Comparison of the Two Physical Effects Phase Modulation and NLAM

Both distortion mechanisms exist because of the 1 over 10000 ratio between the membrane travel amplitudes between recording and reproduction. A reproduction with an extremely large area loudspeaker with negligible membrane travel amplitude (e.g., 1μm) would avoid these distortions. Both distortions are proportional to the membrane travel amplitude, which is highest at low frequencies.

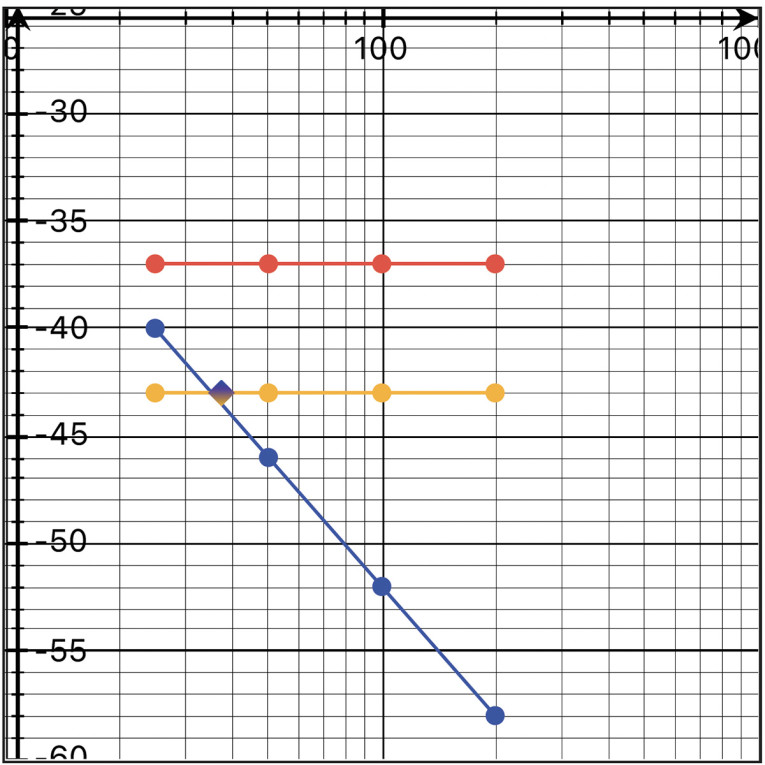

The phase modulation is independent from the listening distance. The two horizontal lines (red for 5mm membrane amplitude, yellow for 2.5mm membrane amplitude) show this in Figure 8. However, the phase modulation is proportional to the frequency, as the phase increases with frequency for a given membrane travel amplitude. So, it is mainly a problem for two-way loudspeakers with a high crossover frequency, but definitely a general problem for high-end loudspeakers.

The NLAM (the blue line in Figure 8) decreases by 6dB for each doubling of the listening distance. It is mainly a problem for close listening and measurement distances and can be neglected for listening distanced above 3m. The usual characterization of loudspeaker chassis at a measuring distance of 0.5m in an anechoic chamber, which is then re-computed for 1m distance is definitely not adequate for the measurement of harmonic distortions at significant membrane travel amplitudes.

In Conclusion

At close listening/measurement distances, the NLAM-generated harmonic and non-harmonic intermodulation distortions may dominate distortions generated by the chassis itself. A measurement of distortions of a loudspeaker in the near field needs, therefore, to carefully consider the NLAM.

The NLAM-generated non-harmonic intermodulation spectral lines lines show the same level as the dominating second harmonic. At larger listening distances the distance independent phase modulation sets the minimum achievable distortion level, if the phase modulation is not compensated.

The non-harmonic Bessel lines of the phase modulation have significant amplitudes at any distance, while the non-harmonic intermodulation spectral lines of the NLAM drop 6dB with each doubling of the distance.

Both distortion mechanisms set a limit for the dynamic of the measurement of harmonic and intermodulation distortions especially at low frequencies. For example, 7mm membrane travel amplitude results at 1m distance in -52dB for the generated second harmonic, compare Figure 8.

Both distortion mechanisms generate a dense non-harmonic spectral floor, which result in the loss of transparency in real music signals. From my point of view, high-end loudspeakers should compensate for the distance independent phase modulation and also the NLAM in case of listening distances below 3m. At a 2m distance and 7mm membrane travel amplitude the generated second harmonic is at about -58dB.

AudioChiemgau offers all electronic modules for building high-end acceleration (motion) feedback loudspeakers including a digital audio processor, which can eliminate both the Doppler effect of the moving loudspeaker membrane and the NLAM. aX

References

[1] K. Küpfmüller, W. Mathis, and A Reibiger, “Theoretische Elektrotechnik – Eine Einführung, 18. Auflage. Springer, 2008, ISBN 978-3-540-78589-7.

[2] R. Lutz, “Improving the Transfer Function of Electrodynamic Loudspeakers,” audioXpress, March 2024

[3] “Damping of sound level (decibel, dB) vs. distance,” Sengpiel Audio, www.sengpielaudio.com/calculator-distance.htm

[4] R. Lutz, “Eliminating Speaker Doppler Distortion,” audioXpress, October 2024.

[5] “Digital Audio Processor AC-DAP01,” AudioChiemgau, www.AudioChiemgau.de

[6] R. Lutz, “Measuring Loudspeaker SPL Response and Harmonic Distortion at Low Frequencies,” audioXpress, October 2023

This article was originally published in audioXpress, November 2024