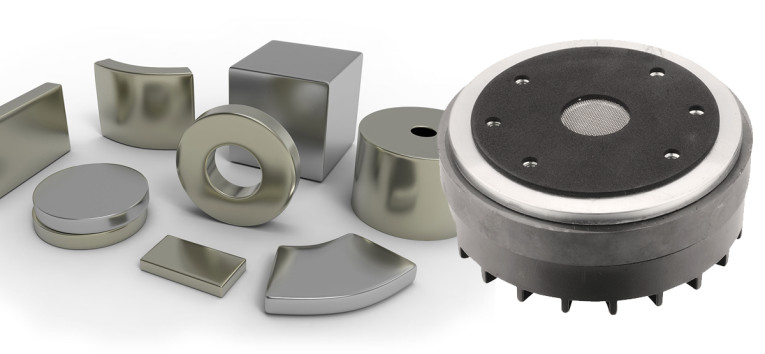

Developed independently but simultaneously by Sumitomo and GM (Magnequench) in the early 1980s, and first appearing in an Electro-Voice compression driver soon after, early neodymium had its issues from corrosion to loss of characteristics when the speaker heated, up to legal issues with non-licensed Chinese vendors. But in the 1990s, performance improved and it seems that as the process was refined, it was the impurities that were one of the main sources of corrosion so mGO (the magnetic strength measured in megaGauss Oersteds) went up along with the long-term stability of the magnets. Neodymium became even more enticing as pricing dropped as many Chinese vendors entered the supply chain.

Alnico vs. Ferrite

Back in the 1950s and the 1960s, magnets made of Alnico were commonly used in loudspeakers. However, a shortage in materials and increased costs for Alnico in the early 1970s precipitated a shift to the widespread use of the ceramic (Ferrite) magnets. Specifically, it was the political and the military conflict at the cobalt mines, which were in the control of the “insurgent forces” in central Africa in the Congo (Zaire during that period) that drove prices up and supply stability down.

I remember a “mercenary surcharge” on Alnico, which was often levied just to get the stuff to the port. By the way, today, cobalt is again nearing supply limits (see Figure 1). While more widely available, the ceramic (Ferrite) magnets were quite a compromise, often deprecatingly called “mud magnets,” requiring huge magnetic structures just to come close to the sound that was more elegantly achieved by Alnico. In the 1990s, most speaker manufacturers started seriously evaluating the potential benefits of using neodymium magnets in loudspeakers.

Although neodymium magnets themselves were more expensive, they allowed loudspeaker motors to be as little as half the weight of comparable ceramic magnet motors, and the cost of the steel magnetic return structure offset some of the bill of materials (BOM) cost.

Sources of Neodymium

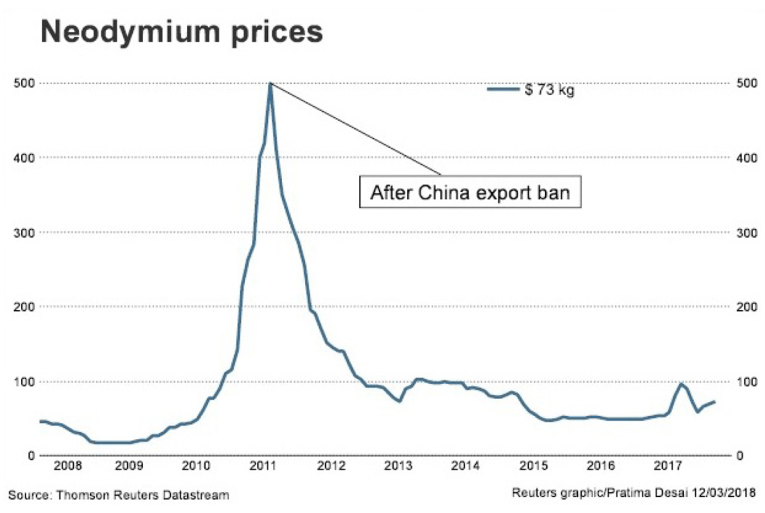

Yet, today's transducer designers think long and hard before going with a neodymium design because, back in 2011, price fixing resulted in skyrocketing magnet costs. The dynamics were more complex than just “price fixing,” rather it was some composite of differing forces ranging from a decision by the World Trade Organization against China on neodymium exports, health, and environmental concerns on rare earth mining, and conservation of resources. The bottom line was that the Chinese government decided to limit and control pricing on neodymium magnet exports (while keeping neodymium pricing down for domestic consumption).

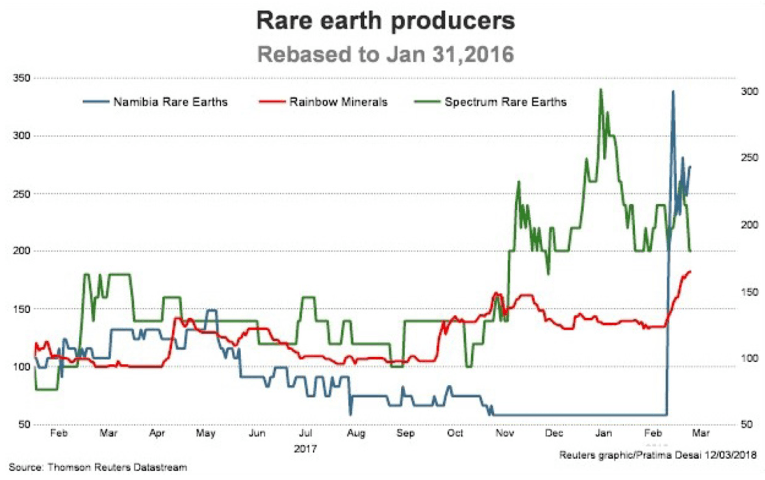

Specifically, neodymium export quantities had quotas. The fallout from the price hike was that many speaker brands brought back their clumsy ferrite designs. In 2012, neodymium pricing fell dramatically and since then pricing has been reasonable —until 2018. The price has slowly been creeping back up and neodymium is now about $70/kg, but still well below the $500 high after China held back shipments in 2010 (see Figure 2).

However, China is not the only source of rare earth metals. In fact, the desert area along the border of California and Nevada is full of rare earth metals. Actually, rare earth metals are not so rare with reserves of about 20 million tons in the vicinity of Mountain Pass, CA. You would think there would be a mine... and there is. I drive by it on every trip I take from the Bay area (Northern California) on my way to CES in Las Vegas, NV. If you take Highway 15 on the way to Las Vegas and turn onto Bailey Road (just before the Nevada border), you are at the mine.

The story is that the Mountain Pass deposit was discovered by a uranium prospector in 1949, who noticed the high radioactivity. Rare earth metals and uranium tend to be found together. The Molybdenum Corp. of America bought the mining claims, and small-scale production began in 1952. Production expanded greatly in the 1960s, to supply demand for europium used as a phosphor in color television picture tubes.

The deposit was mined in a larger scale between 1965 and 1995. During this time, the mine supplied most of the worldwide rare earth metals' consumption. The Molybdenum Corp. of America changed its name to Molycorp in 1974. The corporation was acquired by Union Oil in 1977, which in turn became part of Chevron Corp. in 2005. Along the way, Molycorp absorbed GM's Magnequench along with their patents for neodymium.

In 1998, the mine's separation plant ceased production of refined rare earth compounds. The mine closed in 2002, in response to both environmental restrictions and lower prices for rare earth metals.

Environmental issues? I mentioned the dirty secret that where you find rare earth metals is where you also find radioactive ores, and radioactive slurry is a by-product of the separation process of ores. The extraction process requires separation of multiple metals from a single deposit and is difficult and expensive.

In 1998, chemical processing at the California mine stopped after a series of wastewater leaks. Hundreds of thousands of gallons of water carrying radioactive waste spilled into and around Ivanpah Dry Lake. The mine was mostly inactive since 2002, though processing of previously mined ore continued. China’s rare earth ore mining is worse, with the miners exposed to radioactive dust (which is the official reason, along with preserving resources for the Chinese government to limit production in its rare earth mining industry).

In 2008, Chevron sold the mine to privately held Molycorp Minerals, LLC—a company formed to revive the Mountain Pass mine. Then in late 2010, China artificially raised the price of rare earth elements by restricting exports of neodymium. With this huge opportunity facing them, Molycorp spent hundreds of millions of dollars on a state-of-the-art ore-processing system for rare earth metals. The plan was to turn Mountain Pass into the cleanest, most energy-efficient, most reliable source of rare earth metals on the planet.

Meanwhile, whether by plan or inadvertently, China’s neodymium prices plummeted from 2012 onward. Molycorp couldn’t compete and filed for bankruptcy in June 2015. At the time of the bankruptcy, Molycorp had outstanding bonds in the amount of $1.4 billion.

For now, we may be in the eye of the storm — calm for the moment— but with the likelihood of trade wars coming and neodymium being a pressure point for electric cars (not to mention loudspeakers) — China may manipulate huge price hikes on neodymium. The Mountain Pass mine could have been pivotal to break this strangle-hold. This resource would seem to be an obvious ace in the hole with both the unlimited reserves and the world’s most advanced refining processes, scaled for massive production—just waiting to spring into action during a trade war or other Chinese monopolistic price fixing moves.

Neodymium Uses

However, the speaker industry is not the main driver (sorry for the pun) for neodymium. Rather, we are at the start of the electric vehicle (EV) industry’s shift from the AC induction motor to the lighter, stronger, and more efficient neodymium permanent magnet motors. BMW, Nissan, and Geely (the Chinese guys that own Volvo) led the way and now the Tesla 3 Long Range is the first step to a total switch over of all the Tesla models to neodymium motors. With neodymium motors, Tesla can upgrade its Insane and Ludicrous buttons to whatever comes next.

If you have been to any of the cities in northeast China, the dense air pollution is alarming — far worse than the heavy smog alert days in Los Angeles, CA, back in the 1980s. The Chinese government has mandated a pivotal shift to EV production as a path to reverse the air quality problems.

An article from the June 2018 issue of Forbes reported that China had the highest sales figures of any nation by far with 579,000 EVs sold. The vehicles had a 2.2% share of it in 2017. That’s more EVs than there are in the US, where their market share stood at 1.2% last year.

Global demand of 31,700 tons of neodymium in 2017 has already outstripped the supply by 3,300 tons. Demand is expected to climb to 34,200 tons in 2018 and 38,800 tons in 2019, leaving larger deficits and creating a tug of war between the global speaker industry and the Chinese EV industry.

Well, in 2017, MP Materials, a consortium created by JHL and QVT Financial, acquired Mountain Pass out of bankruptcy for peanuts ($20 million) and restored it as one of the premier global materials operations. (Update: In 2019, MP Materials achieved run-rate production of >30,000 metric tons of rare earth concentrate, or ~15% of the global market, and downstream processing and separations facilities are projected to restart at the end of 2020.)

A Chinese-led consortium including rare earth minerals miner Shenghe Resources were allowed to keep 9.9% of the operation, as anything more would enact the Committee on Foreign Investments in the United States (CFIUS), an interagency federal government committee headed by the Department of the Treasury, that regulates strategic businesses (e.g., critical material mines) that arouse national security or critical infrastructure concerns.

While the present Presidential administration gives lip service to “America First,” when the mining industry representatives met with Trump’s chief strategist (at the time), Steve Bannon, to persuade him that the US should nationalize the country’s only mine of rare earth minerals, this fell upon deaf ears. Apparently, Mountain Pass was not a higher priority than adding a short stretch of border wall.

In the next article, we will discuss another resource — neodymium recycling plants. VC

Read Part 2 of this article here

This article was originally published in The Audio Voice newsletter of August 23 and 30, 2018. An extended version, also divided in two parts, was later published in Voice Coil magazine in November and December 2018.