Born into a musical family in Hungary (his father was the renowned composer Béla Bartók, his mother the famed pianist Ditta Pásztory Bartók), Peter Bartók traveled across Europe during World War II to join his parents in America — as it turned out, only a few years before his father’s fatal illness. The story of his journey, and Peter Bartók’s reminiscences of his father and family, can be found in his book, My Father, which I read and found delightful.

Peter Bartók cut records and made tape recordings; much of his work was done using equipment he designed himself, being dissatisfied with commercial quality gear. In that respect, he qualifies as one of the pioneering audio engineers of the LP era, and I’d venture to say his best work stands up to many of the audiophile recordings released since.

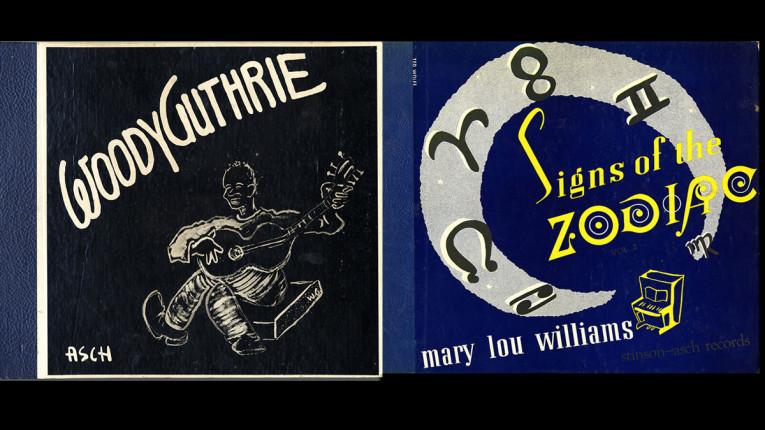

He founded Bartók Records in 1949, which produced critically-acclaimed recordings of his father’s works and other contemporary classical music. But Peter Bartók’s greatest public impact probably came from his behind-the-scenes involvement with Moses Asch’s Folkways Records; an entire generation grew up learning about American and world traditions from those thick records with blue labels and heavy, double-pocketed jackets containing extensively-notated booklets. Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly, the New Lost City Ramblers, ethnographic tapes from every corner of the earth — even the first recordings of avant-garde composer John Cage — passed through the crowded office of Moses Asch, and the cutting amplifiers of Peter Bartók.

After Mike Seeger (a founder of the Ramblers) was kind enough to put me in touch with him, it seemed logical to start there.

Can I begin by asking about Folkways?

Peter Bartók: I used to do a freelance recording service. I had a little recording studio that I made out of my father’s apartment in New York initially, and then I moved into something more appropriate. My business is registered as having started in ’49, and Folkways was one of my earliest customers for cutting long-playing masters. They brought the tapes, and we transferred them on long-playing lacquer discs, which then went to the factory and were plated. In my initial work, people came to the studio, played the piano, and recorded. They walked home with a disc.

But Folkways brought more interesting folk music records done in the field, which had to be edited sometimes, and then made into long-playing masters. The first record, I think, was a 78 that I made for [Asch]. Just after I started working in this field, my own first record—that I published on my own label — was a 78. I resisted the change [to LP], because, as a principle, it was a little bit of a downgrading of quality, because of the slower linear velocity of the groove.

And then I did like good-quality 78 records; they were capable of wonderful reproduction, once you got rid of the shellac as the pressing material.

When the vinyl was introduced, then they were superb. How late did you continue cutting 78s?

PB: As soon as the LP came out, I stopped; there was no reason to continue making 78s once the LP was introduced. It was possible to get the same good quality, as long as you didn’t try to jam too much music on one side. The longer an LP is, the less good the quality.

On Tape

How did you first meet Moses Asch?

PB: Well, just exactly who introduced me to him, or who recommended my services to him, I do not know. He brought discs to be copied, and then he brought tapes to be made into masters. I was on 57th St., and he was on 47th St., so it was not difficult for him to get to me.

He was a wonderful man; he was so imaginative and so full of ideas, and he worked day and night. Which to me was not unfamiliar, because my father was that kind of a person also. It was wonderful to work for him; he was such a colorful personality, and it was nice to interrupt the work and go out to lunch, and then come back and resume — in those days I could do that.

And then I got tape equipment; initially I had only disc, because the only kind of tape recording that I knew was not of very good quality. There was a machine called [Brush] Sound Mirror which people had in their homes, but I thought, “Oh, that’s not capable of really good reproduction.” Finally, a salesman from Ampex demonstrated the Ampex quality, and it made everything very easy. Let us say there was a set of 78 records that we had to copy on an LP; it was easier to put it first on tape than to keep changing the original source.

My first LP record was still done on discs, and during the cutting of the LP master I had to switch the source from one turntable to another, because it was a 15-minute piece which the musicians could never get right from beginning to end. There were two records, one was good until the middle, and the other was good after the middle, and so the two had to be combined—without using tape. After that I got the tape.

So that was your first machine. Was that the Ampex 300?

PB: That was a 300; I accepted at that time Ampex’s claim that 15 [ips] is a good speed for making records. The Sound Mirror, which I didn’t like, was going at 7½, and of course the higher the speed, up to a point, the better the quality. And at 15, as I found out later, the quality is really not as good as at 30. Before that time, Ampex marketed a machine which ran at 30. The reduction to 15 [ips] was claimed to be an improvement, but actually it sacrificed some of the quality. So I went back later to 30 [ips] once I realized that 15 was a compromise.

Compromising the sound quality for playing time.

PB: Well, yes, to use less tape material, but a lot of sound was lost, and it had to be equalized excessively to get the same — to get all the frequencies there.

Then I received many tapes from Europe that were still 30 ips, and I realized that 30 ips is the quality that I need.

Rolling His Own

So we converted the machines by putting a sleeve on the capstan. The Barpex, I used to call it, combined the two names. Ampex didn’t like that kind of thing at all; I bought spare parts, replacements, for Ampexes, and instead I put them together into a machine. But the parts could be had, so... The idea was that, when you edit tapes, it’s awkward to bend over a factory-made machine. I wanted the machine to be a desk, where I can spend the whole day and work comfortably, where I can put my knees under the desktop, and not get tired. So we decided to build a machine into a desk.

I’m not the only one who did this; people told me that they encountered a similar machine at RCA studios, for editing,[which] went even one step further. They put [in] four turntables for reels, so that they could switch from one reel to the other at any time without having to remove reels from the turntable. It made editing more easy; we had to keep on taking the reel off and putting the next reel on. RCA could do it by taking the tape from the other reel. [Pause] Editing tapes was a lot of fun.

Yeah, it was. What else did you do to this machine? It had the reputation of sounding better than the stock machines.

PB: Well, the amplifier was my design. I didn’t use the stock amplifiers for either recording or playing back. I built my own. And then, for disc cutting too, I built the amplifier.

Could you talk about those amplifiers?

PB: Well, I was not happy with standard technology. The recording stage, the power stage, of the recording amplifier was a single tube, and I preferred push-pull, an amplifier which uses two tubes in a symmetrical arrangement. All my electronic equipment was home-designed and built; I just have certain principles I like to follow.

Did you use push-pull all the time?

PB: For power, I learned in the beginning that that was essential. For minimum distortion, that circuitry is necessary. And of course today, anything you buy is push-pull. Anything that drives a loudspeaker or some other power-consuming device, like a cutting head.

So what tubes did you use for the outputs on the Bar-pex?

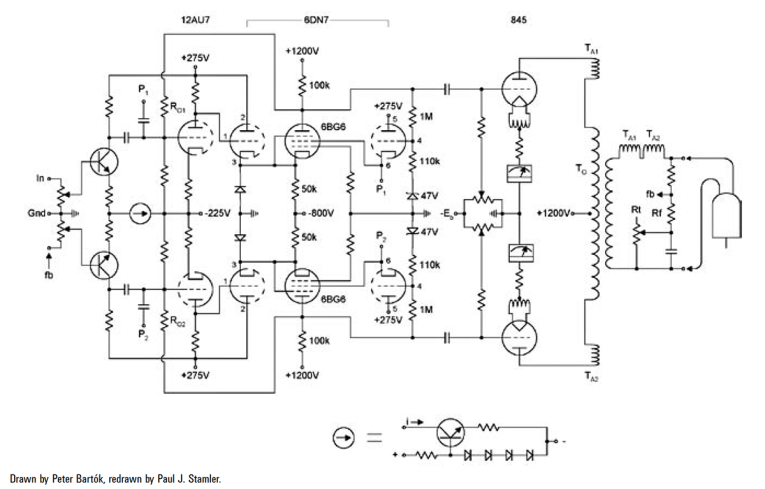

PB: For tape recording, you don’t need a large, very powerful output stage, because the recording uses relatively little power. But still a little bit more power than what you get from a single tube. I think one of the tubes that could be used was called a 6N7, two triodes—I still use such a machine for copying my tapes. For the disc, it was very different. The disc needed a lot of power, and so I used what people call “big bottles,” I think they were 845s.

The 845 is a transmitting triode.

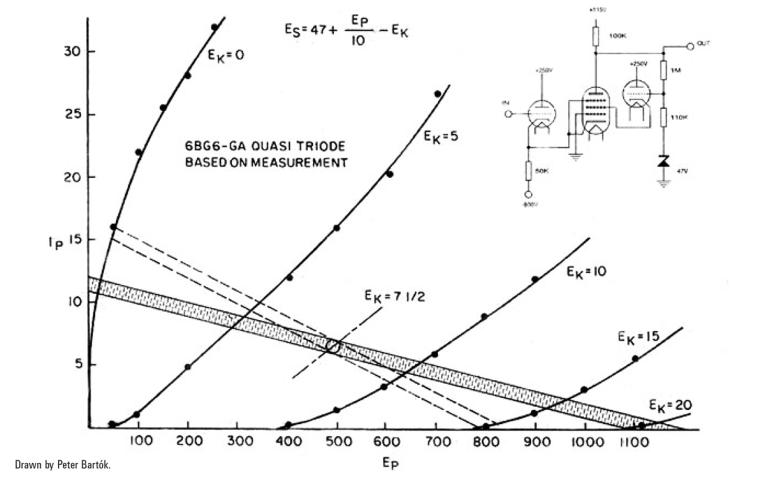

PB: Yes. Well, transmitting needed power, and cutting a disc needed power too. [See Fig. 1, and comments on the cutting amplifier in the sidebar “Design Notes by Peter Bartók.”]

Were these feedback amplifiers, or were they open-loop?

PB: Oh, they were definitely feedback. Feedback is necessary, even [for] tape recording. You have to consider that you feed into, not a uniform impedance, not a resistive impedance, but into a coil, which will have a high impedance at high frequencies and low impedance at low frequencies. And that has to be taken into account in the design of the amplifier.

Whose transformers did you use? Do you remember?

PB: Yes, Peerless. It was possible to record tape without a transformer, but when it became push-pull, then a transformer was necessary. The Bar-pex didn’t record; I used it only for playback. Editing and playback; another machine was used for the copying.

One thing that was useful in the Bar-pex being so big: when we cut discs, it was necessary to widen the grooves from each other in loud passages, and let them come near to each other in soft passages, to conserve space. This made it necessary to know, one complete revolution of the disc in advance, when the music is going to be loud. The disc makes about one revolution in two-seconds, so it was necessary to have an advance playback head, just to sense how loud the music is going to be. The tape had to travel a large enough path from the reel, first through the advance head, and then two-seconds later on the playback head that we are listening to.

Which at 30 ips would be —

PB: Would be 60", so the desktop had to be large enough for that. I am quite sure that all the people who cut variable-groove discs had to have such an arrangement. So it’s not my invention.

I see. Did you regulate the power supplies?

PB: Some power supplies had regulation; Ampex had a regulated power supply also, for the low-level stages, so that there would be no variation. Push-pull makes the regulation less necessary. And feedback, once you have an amplifier with plenty of feedback, then the exact voltage at the power supplies becomes less critical. I have used [regulation] when it seemed necessary.

BH the Parts Perplex

What did you use for passive parts, for resistors and capacitors and things like that? I gather that the variety that is available now wasn’t available in the 1950s.

PB: I still use a monitor amplifier built in 1950, and that really survived a lot of things. [This was the Sarser-Sprinkle “Musician’s Amplifier,” an American version of D. T. N. Williamson’s pioneering amp2. Peter Bartók’s amplifier was built for him by David Sarser.] For critical applications we tried to use wirewound resistors, which were very expensive compared to the carbon, but they were not noisy. Carbons were prone to become noisy at times; you never knew when it was going to be noisy or not, but the wirewound was more reliable.

Today they have deposited carbon. Today — by today I mean twenty, thirty years ago! [Laughs] Because today I wouldn’t even know where to go and get some proper parts if I wanted to go and build something. Radio Shack is the only source here; they have very limited supplies. But fortunately things still work.

And then, of course, the other critical component that is capable of giving you a lot of trouble is the capacitor. Coupling capacitors develop leaks, it was always a problem; much of the time, if something isn’t used for ten years and you turn it on, you find out some things have to be replaced.

Did you use oil-filled capacitors, or did you use paper, or...what did you use?

PB: For power supply filtering, the electrolytic is really essential, because you need very large capacitance. In certain places I know oil-filled was used, and of course paper was used for coupling from one stage to the next—low leakage, you were hoping that it would work. And then came Mylar, which was a later improvement in technology. Most of my stuff was built in 1950 or thereabouts.

And still sounds good.

PB: Well, with certain replacement parts. When I moved to Florida, almost thirty years ago, I rebuilt many things in my equipment, so I could use hybrid—both solid-state and tubes. I like to use both because tubes do certain things that the transistor doesn’t do, and vice versa.

Could you elaborate on that?

PB: Well, a tube has a very, very high input impedance, and it is possible to attach it to the output of a transistor which has a high output impedance. But if you couple a transistor following another transistor, the transistor has a lower input impedance, so therefore you are loading the previous stage, which the tube doesn’t do. The tube, of course, has a capacitive load, which has to be taken into account, because of the capacitance between the grid and the plate.

Everything can be solved with transistors, but one can do it with fewer components if you, let’s say, combine one transistor and one tube, following it. And I kind of liked making use of both. [Laughs] I like to use equipment with a minimum of components.

And it sounds better with fewer things in it?

PB: Well, if it works correctly, it should sound good. Then it’s up to the microphone and the musicians. The output stage, that’s a different thing. There, a transistorized output stage, I have never really liked.

It’s because transistors have a crossover problem, and they have to operate Class-B, or Class-AB at least, whereas I could make the big bottles of my cutting amplifier Class-A. They generate a lot of heat, but there is no possibility of crossover distortion when you switch from one tube to the other, because both tubes are always working. Even in tubes, Class-B would give you more power or most efficiency with the same number of tubes, but for cutting discs I used the Class-A amplifier with big tubes.

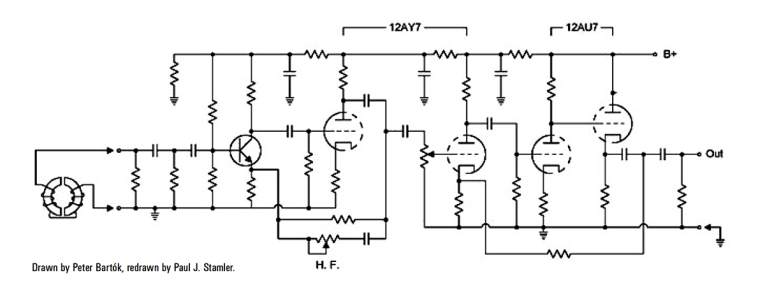

This doesn’t apply to recording on tape, because the power is so little, but even on that I didn’t use transistors for tape recording. I used them for playback, for the low-level stages; for the lowest-level stage in an amplifier a transistor is wonderful, because it’s not microphonic. So you can shake the chassis and nothing will happen. [See Fig. 2 and the comments in the sidebar.]

From Apartment to Concert Hall

In addition to doing disc-cutting for Moses Asch, you also began doing recordings.

PB: Well, the two were simultaneous. I was frustrated just making records for other people, because I wanted to choose the music and the artists, and the acoustic conditions, and everything else that goes with it. It was fun to put out records of my choice and my design, instead of being a servant of other people. Although my first record was done under very primitive conditions, in the same apartment.

It probably sounded good.

PB: No, in that respect — well, it’s amazing that it doesn’t sound worse than it does, but that’s about all I can say for it. The musicians were very good, and we improvised the sound reverberation by putting a loudspeaker in the bathtub. The bathroom was far enough away from the place where the music was played, so, when the microphone finally heard the sound coming back from the bathroom, there was a time delay. And this produced some kind of a room sound, a hall sound. But I learned very quickly that, to get good hall sound, first you find a good hall.

Which recording was this, this first recording that you did?

PB: We called it 001, and later changed it to 901, it’s Bartók’s Third String Quartet.

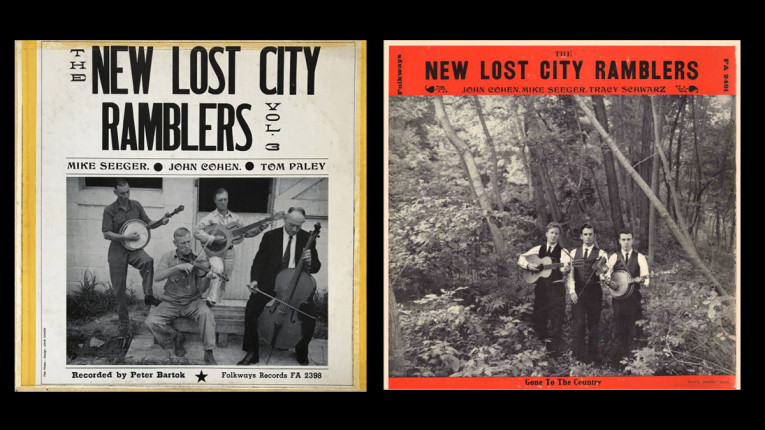

You worked with the New Lost City Ramblers a good deal.

PB: Yes, yes, we had a lot of fun with the New Lost City Ramblers. That was done in the Pequot Library auditorium at Westport, Conn. And the only problem with that auditorium was—it was a very nice small hall, but it was right along the New York-New Haven-Hartford railroad tracks. So we had to record with a timetable, or rather whenever we recorded and a train went by during a take, that take had to be discarded. We were praying that the business for the railway should not be good, so that there would be less frequent trains. The bad times were, of course, the afternoon, the rush hour... But it was not a terrible price to pay for being able to make a nice record.

Finding places in New York was really very difficult; my associate, David Hancock, and I spent days just going from place to place where there was [an] auditorium, trying to determine acoustics which would be suitable for doing recording. I knew a very good hall called New York Times Hall, which was wood-paneled and not too large, very nice acoustics, but it was demolished or something. I never could use it.

So you worked at the Pequot Library. Those first records were in mono; was that a single microphone?

PB: The mono records were not always made with single microphones, because you needed to accentuate, let’s say, one instrument over the other. So it all depended... I once recorded Handel’s Messiah; it was done with two microphones. One microphone picked up the overall sound of the orchestra and the chorus, but we had one small microphone for the soloists that was adjusted to the proper balance. But I like to use the minimum number of microphones. Just an orchestra with one microphone can be very nice, if it’s at the right place.

How do you find the right place when you’re doing that?

PB: It’s partly instinct, but partly walking around with one’s ear open, and where the music sounds good... but one calculates it also. There are very simple principles; if you are too far from the musicians, then they will sound in the background with a lot of room sound, whereas if you go too close, then you lose the room sound, and all you hear is the musicians. You want to have some of both; you want to have the reverberation of the room as well as the original sound, from the proper distance.

When you worked with the Ramblers, how did you record them? What were you using for microphones at that point? Condensers, or...?

PB: I liked the ribbon microphones, the RCA 44-BX, but we also had an Altec, a decapitated Altec.

Oh?

PB: [Laughs] Well, I don’t know if you have seen one —

Is this the “salt shaker?”

PB: Well, they didn’t have holes on top. Initially, [Altec] decided that closing up the microphone and letting the sound enter on the sides, through little slots, was the way to do it. I didn’t like the results at all, when I first acquired such a microphone, and once I took the brave step of cutting off that top—its function was to protect the membrane of the microphone, but at the same time it very much affected the sound. Altec later compromised by putting holes into this top; that became the “salt shaker.”

But I liked to have it completely off; which meant that if somebody, some curious person, went near the microphone, they were always tempted to put their finger into the membrane, and I had to throw the microphone away after that. Later we put [in a] large bulb made of wire gauze, to protect the membrane without affecting the sound, seriously.

So, the decapitated Altec...

PB: It was stainless steel, and we had to take it to some shop where they had the necessary equipment to cut it precisely, so they don’t cut into the working part of the microphone. The whole thing was tiny.

I know that the Ramblers liked the sound of the decapitated Altec for certain purposes. It had a brightness — I think they sang into it. And for the guitars we might have used the 44-B.

Those were certainly some of the most natural-sounding recordings I’ve heard.

PB: [Laughs] Well, I’m glad. They were really fun to make. Those people were wonderful to work with, and I like the music they made.

There’s at least one stereo recording of them that you did4.

PB: I only made the tape; they gave it to somebody else to cut the master, because I never acquired stereo cutting equipment.

Was that a crossed pair?

PB: I think for stereo, we used two RCA 44-Bs. I cannot be sure, but I think we used the Altec to feed to both channels, and the 44-Bs for one channel each. To get the stereo effect you had to have at least two microphones, but I like the third one for accentuating.

I grew up on these records, on the Folkways records that you cut, on the New Lost City Ramblers. So when my own ear-sensibilities were formed, it was to these very natural recordings, without gimmicking. So I want to thank you for doing that!

PB: It was really a pleasure. I miss that kind of work; I am now with music editing mostly. I love it too, and I must do it, but I miss the recording. I am, right now, transferring some of my old editions to CDs, so that gives me a little bit of fun, working with recorded music again. But I have to do this sparingly, because my time is needed for the music editing. We are producing revised editions of my father’s printed music.

A new critical edition?

PB: Well, it’s a revised edition. The so-called critical edition is something that is still in the future, and other people will have to do that.

Cutting Flat — Or Not?

I read an interview with Moses Asch one time3 where he had cut certain discs for Folkways without standard RIAA pre-emphasis; that he cut them flat. What was going on there?

PB: Well, I think that when you say that one cut it flat, it is perhaps an illusion. Because you took a magnetic recording head, and connected it to an amplifier that did not have a 0Ω output impedance, but a finite impedance. You wound up with a rollover, so that the bass would be proportionately reduced, which would then be enhanced on the playback. In fact, to make a disc that is completely flat, the excursions of the grooves at the bass end would have to be so great that it would be beyond the capacity of any cutting head. So you have to take it with a grain of salt; it’s not really flat.

I think he said that some of the Ethnic Folkways series were done without high-frequency pre-emphasis.

PB: Well, it may be that the high-frequency pre-emphasis was something that one built into the amplifier, even if one is not conscious of a so-called pre-emphasis that was later used. One boosted the highs enough to have it there, otherwise you wouldn’t hear them.

The cutting head that Moses Asch used was the same as I later acquired — Van Eps — and those had a very strong resonance around 4,000 cycles [Hz]. So if you cut flat with that cutting head, you actually pre-emphasized all the high frequencies, at least up to 4,000. They had a strong peak. In order to eliminate that, which gave you an unnatural brilliance, you had to build a special filter that compensated exactly for that peak. Which of course was not always the same, depending on the temperature and other conditions, so this compensation filter had to be adjusted, if we wanted a perfect sound.

But if you simply take an ordinary flat signal and feed it to this cutting head, there will be two things that will automatically occur: this high-frequency enhancement because of the resonance, and the low-frequency reduction because of the cutter’s impedance. The cutter’s impedance goes down with [decreasing] frequency. So if you feed it [from] an amplifier with constant output impedance, then you reduce the bass, without specifically designing it that way.

When I cut later with these heads, I built a feedback arrangement, so that I followed the curve; on LPs I followed a higher pre-emphasis than I did on 78s. Anyway, one can control it, so that the turnover would become 500 cycles [Hz], and the high-frequency pre-emphasis begins at [2,122] cycles [Hz], that was the RIAA curve that they prescribed. The peak of this cutting head had to be first taken out completely, and then a pre-emphasis put in.

I think when Moe Asch talked about flat, this is what he meant. He made use of the characteristic of the cutting head. At that time, 4 or 5,000 cycles [Hz] as the peak of this cutting head was regarded as very near the top end of the frequency cut on discs, on 78s, on shellac. And they sounded very good. [I pursued the question further; see the sidebar, “More About Cutting Flat.”—PJS]

I’ve tried playing back some of his ethnic releases with the top end flat, without rolloff, and I must say that they sounded pretty good that way.

PB: Well, if you played them back without rolloff, that would confirm that they were recorded without pre-emphasis. But as I say, that 4,000-cycle [Hz] peak was beneficial, in a sense. Many microphones are built with such a peak, to make people’s voices more brilliant. A flat sound—people regarded a flat sound as boring. Well, within reason.

What happened at that time, before tape, when a disc was recorded, from microphone to disc, and then that was processed as a master, you got a wonderful quality. However, when the master broke or anything, what they had to do was play one of the discs — or maybe a metal mother, which is playable as a disc—and copy it. Then the deficiencies of the pickup that you used for playing the old disc came into play, and of course at the time of the cutting, you multiplied whatever inaccuracies there are in the cutting system.

So the quality went way down when you bought a record, and it was already a copy of another record, or a copy of a copy. And [it was] very seldom that you got a record that was fresh from the wax, that the wax or lacquer was what was cut at the recording session. Because it only lasted so long.

The cutting equipment, these Van Eps cutter heads, I think they were very well designed. Not Van Eps’ design; I think he was copying a German make. They were a vibrating-reed cutter. And there were many other kinds of cutters made, where they had a pivot, or else they had moving coils. But a vibrating reed lent itself to very low distortion, and good transient response. I use it today — to the last LP disc that I cut.

Daring Adventures

When you were cutting for Folkways, especially the Ethnic series, I imagine that the raw material came to you in many different forms.

PB: Yes, much of it came from primitive little tape recorders that people took with them on the field, and we had to do what we could to bring them up to presentable standards.

How would you do that?

PB: Equalizing. We had to sense what the sound needed, what compensation was needed, to bring it to a natural sound. There has to be always enough balance between the highs and the lows, and the middles—not enough to have just the highs and the lows, the middles are very important too—and one has to use one’s ear. Of course, there are limitations, but some of the records could become quite good, even though they came on primitive tapes.

I remember seeing a set of Folkways notes that somehow got reprinted into the booklet that came with the record, that included the cutting notes. It was a reel of tape, half of which was at 15, half was at 7½. And it was telling the cutting engineer to switch the speed at such-and-such a point. (See Fig. 4.)

PB: I never... it must have been recorded in the field, when somebody was running out of tape and...

Yes, I think that’s exactly what happened; these were field recordings [from Alabama, Louisiana and Mississippi]5.

PB: But usually, we would simply make a submaster tape. Because when you cut a disc, there is so much to pay attention to that even thinking about switching the tape speed, that would be a terrible nuisance.

When I take an old tape and put it on a CD, I first have to make a submaster copy, and so the old tape has to be played. It’s not a simple matter, because before Mylar was invented, those tapes were not stable. They stretched, they elongated, they swelled, they deformed. Quite a challenge to try to play an old tape.

Do you have to do things like baking them, or things like that?

PB: [Laughs] I had to do a lot of things with one of my tapes;[it] had to be under special tension, and [I’d] wind it back and forth for a while to try to smooth it out. I had to put a felt pad on the other side of the head, to press the tape against the head, to make contact, because the tape is so fluttery, so wrinkled, that you lost contact. But forcing it against the head and increasing the tension to much higher than normal can help. Then when Mylar was invented, it solved this problem. Today they are the same as when they were first recorded.

Listening Back

What did you use to monitor your cutting and your recordings?

PB: Well, it had to be a good loudspeaker. My first monitor loudspeaker was an old radio set that was called “Spartan” or “Spartone,” I think; I used the loudspeaker in it and even the amplifier which came with the radio. It was in a big wooden cabinet, very nice looking, and it had a loudspeaker cone with a leather surround . . . well, it had a good sound.

Later, of course, I had to buy what I could. The Wharfedale company in England made very good loudspeakers. Today’s loudspeakers are quite good, but they’re very inefficient in comparison, because they achieve a good sound by a lot of damping.

Did you ever use the Altec coaxials?

PB: I dreamed about once acquiring one, but I always put it off and never did. I usually built my loudspeakers from components I got. I remember RCA had a speaker called the “Olson,” which was a big cone with a large diameter voice coil, and then inside, in the center part, was maybe a 2" diameter tiny speaker, for highs, and the two were matched in such a way that it had a very good sound, but I never was able to use it.

Coils and Clicks

When you were remastering 78s, what kind of equipment did you have to work with, in terms of turntables, cartridges, equalizers, and so forth?

PB: Well, there were moving-coil pickups that I used, but initially I had GE and Pickering. I forget now the name of the company that made the moving-coil pickup which I used. It had kind of a square head, in which there was a little moving coil, and once it broke, you had to give it back to them to replace the coil. It was pretty difficult. You can’t get them today, so I wound up with some stereo pickup which I just put into the same socket, and—well, they make very good pickups today.

I think I had a GE with a 3 mil. diameter point—stylus—for [78s]. You have to load them correctly. Then, of course, with 78s, which were pressings, there was always the problem of how to reduce the surface noise without reducing the music. You have to be selective, reducing the noise at those places which contain very little musical information. Overtones that were not there—there’s no point having a lot of noise at 15,000 cycles [Hz] when the record wasn’t made up to that range anyway. We had to sense the upper limit of the recording system when the disc was made originally, then eliminate everything above that.

Of course, later, when something was very important, such as when I copied some old records of my father’s piano playing, I would just put it on 30 [ips] tape and cut out the clicks, one by one. I have spent one month cutting out clicks from an LP of my father’s playing. (Whew.) You have to cut them out where it doesn’t hurt the music. A click that goes with a piano sound has to be left in, because otherwise it interrupts the sound, but you can take out one that is between two sounds. But I think in the early days we were happy to just get the sound from the disc, as much as possible, on the tape.

It’s a long distance to now, when you can take out clicks on the computer.

PB: Well, I never got to that. I used scissors. I had non-magnetic scissors, always on the Bar-Pex. They are still there. aX

References

1. Peter Bartók, My Father (2002). Available from Bartók Records, PO Box 399, Homosassa, FL 34487.

https://www.boosey.com/shop/prod/Bartok-Peter-My-Father-Hardback-Book/713803

2. David Sarser and Melvin C. Sprinkle. “Musician’s Amplifier,” Audio Engineering (Nov. 1949); reprinted in C.G. McProud Audio Anthology, Volume One. Audio Amateur Publications, Peterborough, NH (1987).

3. Gary Kenton “The Audio Interview: Moses Asch of Folkways” Audio 74:7 (July 1990), p. 38.

4. New Lost City Ramblers, Remembrance of Things to Come. Folkways FTS 31035 (1966); this and all Folkways recordings are available as CD-Rs from Smithsonian/Folkways, https://www.si.edu/spotlight/american-folk-music

5. Frederic Ramsey, Jr., ed.; various artists, Music from the South, Vol. 6: Elder Songsters 1. Folkways FP 2655 (1956); see note 4 for availability.

Design Notes by Peter Bartók

The tape playing amplifier (Fig. 1) is about 30 years old; it was the first time I included a transistor in something I built, but I still felt more comfortable with tubes. What dictated the transistor input stage was the enormous gain required (at low frequencies) and the trouble with microphonics if tubes were used at such a low level.

Followed by only a grounding resistor and an open grid, the transistor with a high resistance load can produce a large gain with very few components. The grid-to-plate capacitance of the following tube is of no consequence, as the gain at high frequencies already is low anyway. I may have included a capacitance-resistor combination in parallel with the transistor’s load, so feedback would not be the only factor relied on in obtaining the 6dB/octave drop with frequency rise, but the main equalization determines the frequency response. The variable resistor high frequency levels off the response at a desired point and is, in effect, a variable high-frequency boost that is optional for every tape played. That, and the potentiometer for volume, are the only two controls.

I was lucky to find the sketch of the cutting amplifier (Fig. 2) just where I left it at the time I built it, in 1980; otherwise, I would have drawn the circuit of its predecessor. I forgot that this one also used transistors. My previous cutting amplifier also used 845 output tubes, but otherwise it was an old style circuit, with many coupling capacitors, and it had a tendency to motorboat. I also wanted to be sure that the stage driving the 845s had ample signal scope, needed by these tubes.

The input stage is a differential circuit to provide positive and negative inputs and push-pull output. The second stage is a single 12AU7; the third stage, direct coupled, uses two dual triodes (unequal) and two high voltage pentodes but is all one stage; I wanted to cathode-drive the 6BG6, so it needed a cathode follower to drive it and another to provide screen voltage. Its screen voltage is obtained from a voltage divider, a zener diode, and a cathode follower, so the screen current fluctuations should not change the desired screen voltage. I regard the pentode used this way as a “quasi-triode,” with characteristics as on the enclosed curves (Fig. 3).

The little transformers TA1 and TA2 were added later, to compensate for the limitations of the output transformer that was not good above about 15,000cps [15kHz]. These are air-core transformers, wound on plastic forms and, connected in series with the main transformer windings (which behave somewhat like short circuits at the very high frequencies), transmit only the high frequencies.

The feedback circuit provides for a turnover frequency of 500cps [Hz] by increasing feedback below the turnover frequency (Rf and Cf), but provides a “turn-back” to approach flat output below the cutterhead’s inherent turnover frequency (determined by its own inductance and resistance), adjustable for the particular cutterhead used. Milliammeters in series with the cathodes of the 845s allow setting of the operating point and balancing of the two tubes.

The diodes, from ground to cathodes of the [first] 6DN7 and 6BG6 tubes, have no function in normal operation, but prevent the appearance of a large negative voltage at these cathodes if either of the tubes were pulled out or did not function. Feedback resistors R01 and R02 stabilize the operating point of the 6BG6, and the tiny capacitors [at] P1 and P2 were needed to suppress the tendency for parasitic oscillations to happen when the output transformer is inside the feedback loop.

Although not part of the amplifier, let me add that the Van Eps cutter I used also underwent a little modification: replacement of the pole pieces to provide a little stronger magnetic field to the moving reed, and I wound the driving coil to the desired impedance (Mr. Van Eps’ son was kind enough to provide some empty forms). There was a time when I considered replacing the Van Eps head with something more modern. I even had a fancy new cutter with its own amplifier in my studio for a tryout; the transient and frequency response of the Van Eps, however, proved far superior, and [it] went back into service. [In the Audio interview3 Moses Asch notes that Fred Van Eps, who built the cutting heads, was also a renowned player in the “classical banjo” tradition; his records were very popular in the acoustic 78 era. I have a couple of them.—PJS]

The large thumb screw that held the shank of the cutting stylus was replaced by a tiny Allen set screw about the size of a poppy seed to reduce the mass of the moving element. The shank of the stylus itself was slightly shortened to bring the resonant frequency of the stylus in its shank to about 18,000 [Hz].

Thank you for asking for this diagram; it was fun for me to review the circuit that I put a lot of effort into at the time. The amplifier worked satisfactorily during the short time I was able to use it, before the curtain went down on LPs. It is nice to look at it once in a while, although sad that it is not likely to ever cut a record again. aX

More About Cutting Flat

After discussing the question with Peter Bartók in our interview, the quote from Moses Asch about cutting records “flat” kept nagging at me, so I dug through the basement until I found the original quotations. They came from an interview published in Audio magazine a few years after Asch’s death:

"My philosophy was to make a ‘flat’ record. This means that the frequency used was as flat as possible to the sound that it produced. My practice has always been to record things as they are, with the simplest means of reproduction. All my records were recorded on a flat surface with a needle moving at a constant speed."

"...the LP pinched the tracks, so the high frequencies were bad and the low frequencies were suppressed. Because the technology was not yet able to reproduce sounds that the public wanted. London Records started to boost the highs on their recordings, which they called ‘High Fidelity.’ All the other record companies went with the high boost. I knew that I was documenting these sounds and that 100 years from now somebody could reconstruct what it sounded like by having a flat curve. For the other records, they would have to know how the boost worked and reverse it3."

I sent these quotes to Mr. Bartók, asking him to comment; here are excerpts from his reply:

PB: Before returning to that point, we should clarify what we mean by “flat” recording. There are at least two kinds:

1. Constant velocity, meaning that a signal of a specific intensity will make the disc cutting stylus move at the same maximum lateral speed regardless of frequency. Thus, a 220Hz groove will not only have double the wavelength of a 440Hz groove of the same intensity, but will also make double the excursion peak to peak.

2. Constant amplitude: here the 220Hz signal will cause the stylus to move at half the maximum speed of a 440Hz signal of the same strength, but the two will have the same excursion.

Each method has its obvious limitations: with constant velocity, the stylus (and groove) excursions will be very large at low frequencies, whereas with constant amplitude the lateral stylus velocity will be so high at high frequencies as to be untrackable by a playback stylus.

The magnetic cutterhead inherently recorded constant velocity but, as its own impedance became lower at lower frequencies, it tended to short out the output of the recording amplifier and recorded at constant amplitude below the frequency where its impedance was the same as that of the amplifier, the turnover frequency. A cutterhead using the principle of a twisting crystal would record at constant amplitude up to the point where the (capacitive) impedance of the head would be smaller than that of the amplifier, or the mass of its moving element would not allow the high velocity required. Eventually the turnover frequency was not determined by cutterhead impedance but by equalization.

When Mr. Asch spoke of recording “flat,” I am sure he meant “above the turnover frequency.”

The RIAA recording curve was not yet invented at the time Mr. Asch made his fine records; the idea of boosting high frequencies was born out of a desire to reduce the surface noise of shellac pressings. If the record was made with boosted high frequencies, it needed to have a compensating high-frequency reduction on playback, thereby reducing the high-frequency component of the surface noise. It was assumed that high-frequency sounds had very little intensity and they could be boosted without any ill effects. I believe the limitations of high-frequency pre-emphasis were soon demonstrated by the distortion at some intense high-frequency signal, such as a cymbal crash.

I am sure that technicians used equalization similar to pre-emphasis just to compensate for the other-than-flat frequency characteristics of equipment. Microphones, amplifiers, cutterheads could be deficient at high frequencies; the famous RCA 44-BX, fine ribbon microphone, required a considerable high-frequency boost to become flat. Even when a master disc was very good, high frequencies were lost in the plating process if silvering was used (as in most instances); gold sputtering, when obtainable, did not have the same adverse effect.

On the other hand, recording the high frequencies even “flat” was not always achieved in early records. Besides the previously mentioned limitations, many records were manufactured, not from a master disc that originated at a recording session, but from a copy. Exceptions were records made so that the pressings you purchased could be a product of a plate made from the initial master recorded at the original session. There were excellent instruments among old microphones, cutterheads, and amplifiers. I have played early 78 rpm records Mr. Asch made that were first-generation pressings of remarkably good quality.

I believe Mr. Asch was aware of the distortion possible with high-frequency pre-emphasis and sought to produce records with clean sound. Mr. Asch was a pioneer in this field, and I have learned much from him — not limited to recording technology. aX