Grimm, Tent, and van Willenswaard go back to the 1980s of last century where they discovered high-end audio though common projects and even running their own publications. Already at that time, the interest was in comparing the results of listening tests and measurements and trying to find out what made a piece of equipment sound good and how that correlated with measurements. All those questions haven’t been fully answered yet, but a lot of insight was gained and subsequently put into practice.

Eelco Grimm cut his audio teeth recording music with his company “Fairytapes,” which used equipment designed and built by his friends Peter and Guido. After hearing an Audio Engineering Society (AES) presentation by Bruno Putzeys about a novel ADC, they asked him if he would license his design. Instead, Bruno joined the partnership. Eventually, Bruno Putzeys left the company to explore other paths. Peter van Willenswaard has nominally retired but is still very much involved in the company’s designs.

With Eelco Grimm initially focused on studio work and Peter van Willenswaard and Guido Tent on home hi-fi, they were in the unique position to benefit from experiences and developments in both areas. This has been a common theme for Grimm products to this day. Although not often realized, the goals and requirements for equipment in both recording and reproduction contexts have many common elements, probably the most important being the need for neutrality, while still being able to convey the emotional content of the music.

That may seem contradictory, but as Eelco Grimm explains, neutrality is a multi-dimensional property. A speaker can be neutral with a flat frequency response, or in its dynamic behavior. An amp can be neutral as in very low distortions but can still sound different to another amplifier which also has low distortion. So, it is a whole complex of “neutralities” that must be balanced without compromising the reproduction of the emotional content of the recording. Not easy to put into hard numbers, but Grimm Audio’s success heavily leans on decades of experience and research into these factors by the diverse group of partners.

Grimm Audio employs about a dozen staff and, uniquely, strives to keep all significant activities in-house. “We don’t outsource assembly for instance, but build all our products in-house, under our own control. We also do all our R&D in house, and in fact our R&D staff far outnumbers the assembly and logistics manpower. We write our own software, and we go so far as to write our own software libraries—reliability and long-term support are very important to us!,” explains Guido.

Pure Nyquist

As an illustration, Eelco Grimm talks about how the team approaches D-A conversion.

“We all know that the ‘Perfect Sound Forever’ adage from the early CD days really missed the mark. There’s a lot that can still go wrong in a bit perfect transfer. For a start that’s because digital conversion is largely an analog affair.

"In a DA converter, the power supplies and the output circuitry are clearly analog. But also, the final stage of conversion within the DA chip, where digital bits are turned into analog voltages, is more analog than digital, for example in the jitter on its clock. This final stage on the edge of digital and analog appears to be one of the most sensitive ‘analog’ parts of the whole audio system. That means that for example power supply noise is very critical.

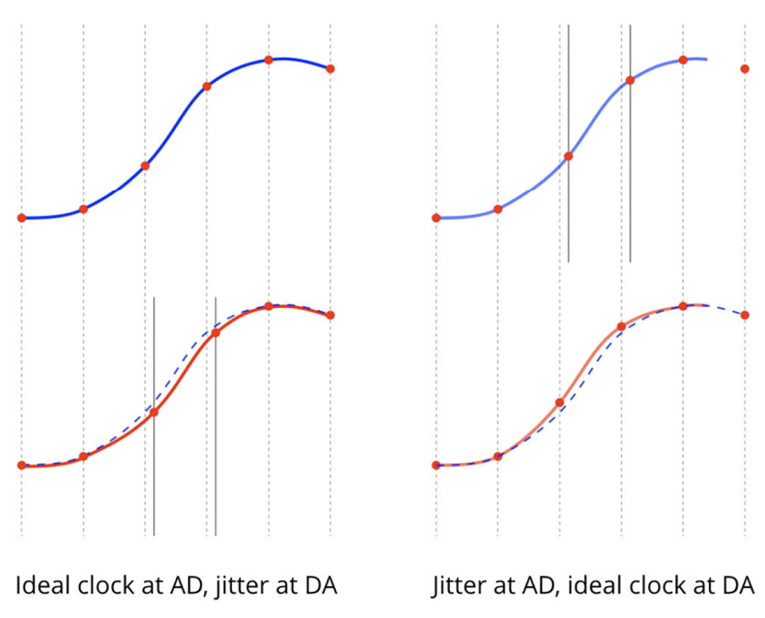

"But it’s not just the analog side that matters. We figured that if jitter is a correct conversion at a slightly wrong time, an amplitude conversion error is a slightly wrong amplitude at the correct time. Both potentially have a similar impact on the overall reproduction quality (Figure 1). Mind that amplitude errors are not limited to classic multibit converter designs. Rounding errors like quantization noise are also a form of amplitude error. Important to note is that these errors already have impact at a very small timescale, so the usual solution of applying dither has only limited effect. Dither solves the problem statistically over time, but not instantly.

"And, if you think about these very short timescale effects, what is then the effect of all that processing we do in filtering, decimation, and such? Do we really have enough resolution to avoid these very small (timescale) effects? To gain more insight, we performed several experiments that were real eyeopeners. If you dig deep enough, all those things such as clock circuits, oscillators, power supplies, mechanical vibrations, EMI, rounding errors in decimation filters, all those so-called ‘minor issues,’ have their effect, and are often audible.

"And so, you end up with shunt regulated power supplies with 130dB noise and ripple suppression, which continues to 1MHz ... And you start to understand the origins of those “magical” stories, for instance, that painting the edges of CDs green had an audible effect. The resulting absorption of scattered light inside the disc very slightly improved the readability, which was measurable in the positioning servo activity of the CD drive. Since the servo and the oscillator often share a common power supply or ground, this resulted in a measurable (and audible) change in jitter. Ultimately, this is an example of bad engineering. The power supply of an oscillator needs to be as clean as possible, and currently we are getting down to 2nV/RtHz.

"Back to the impact of rounding errors in decimation filters. In this context, it is interesting to reflect on the popularity of non-oversampling DACs in some quarters. If you expect that your replay electronics are impervious to a load of high-frequency hash and lots of aliased signals, then leaving out the filter means you will not make any processing errors in that area. Pick your poison. But of course, the real solution is to remove all the images with well calculated filters, which means: with the smallest calculation error. The actual filter magnitude shape, the roll-off, is maybe the least important factor.

"For the MU2 (discussed later) we have developed a filter that is pretty much ideal in both the time and the frequency domain, and therefore we do not offer switchable filters. We don’t want to bother our customers with the burden of having to listen to a sizable portion of their music collection to determine what sounds best, only to find that on another day or with other music they would prefer another setting. It is subtle, and dependent on the conditions and music. We really want our customers to listen to their music and enjoy it, period! We get a lot of feedback from people telling us they stopped their cable neurosis and whatnot and just play and enjoy their music. And, in the end, that’s what makes us happy, that’s what we are after. That’s the dream we are building, both for us and our listeners.”

Grimm’s team found that getting the amplitude errors low enough required much more processing power than was available in typical converters, which led to the use of a powerful FPGA calculation engine in the MU1. It offloads the first (and most demanding) upsampling stage from the DAC chip to the FPGA. It was decided to output the signal in AES or S/PDIF form to the DAC so the MU1 clock quality could be transferred to the DAC (remember that clock and amplitude errors have similar impact). That is the reason why the MU1 does not offer USB audio — the clock in the DAC would be another unknown. By offering the signal in AES or S/PDIF format with its embedded clock, Grimm makes certain that the DAC is benefiting both from the MU1 processing and its high-quality clock.

A typical audio chain has many different pieces of equipment that rely on each other to get the signal from the media out into the air. And you can design the very best piece of audio electronics, but if the parts of the chain before or after are not up to the same high standard, your efforts do not bear fruit! So, Grimm tries to keep the whole chain under their own control. On the recording side, they offer everything from the converter, as well as their own cable designs, to have full control from sound pick-up to the digital audio file and guaranteeing pristine performance: the CC1 and CC2 World Clocks, and the UC1 converter.

From MU1 to LS1

The MU1 is the heart of Grimm Audio’s music system, and it is much more than “just” a streamer. It has not just a Roon End Point but also a Roon Core on board. And it has three inputs for physical digital sources. There are three XLR and RCA outputs providing several AES and S/PDIF signal sources, which can be used for stereo DACs but also support surround playback. The (AES digital) Cat5 output of the MU1 can be directly coupled to their acclaimed speaker, the LS1 series. This is the ideal situation because everything, from source to the acoustic output, is now under Grimm Audio’s control.

The LS1s do look quite different from the usual speaker shape, whether Pro or Home Hi-Fi oriented. Calling the LS1x a speaker is missing the point. This “speaker” is a complete audio system with digital and analog inputs, power supplies, several channels of Class-D amplification and a powerful DSP system that ties it all together. The form factor is unusual for a speaker. Much thought has gone into it.

The LS1 has a relatively wide baffle but is quite shallow, and has extremely rounded sides, that double as stands. This shape is based on a solid engineering approach, that started with the realization that in principle, we can never exactly reproduce the original sound field as shown in Figure 2.

Apart from that basic issue, the room adds its own reflections and reverberations as a function of the speakers’ directional pattern over frequency. Wrangling such problems into an acceptable compromise is not done by starting with what you want to achieve, but rather by looking at and prioritizing what you want to avoid. [1]

A flat, low distortion speaker sounds great in an anechoic room, but in a real room you’ll have to deal with off axis radiation; too wide makes that trumpet sound as coming from all directions; strong frequency dependent dispersion makes the direct-indirect sound balance quite frequency dependent as well.

As Eelco explains, an omni dispersion at low frequency is acceptable, but we need to keep mid to high frequency directionality under control. A transition to omnidirectionality below 250Hz is fine, and if we can get reasonably constant directivity above that, we have a design goal we can work to! Wide baffles have a bad rep but that is not because of the wide shape, but because of the strong diffraction at the edges. Rounding off the edges generously takes care of that, and this is immediately apparent in the LS1 series, where the rounded sides double as stands (Figure 2).

“With the tweeter above the woofer, as is customary, you would also need to round the speaker top similarly, but that looks plain ugly, so we chose to place the tweeter below the woofer and round off the bottom of the baffle. The edge diffraction on the woofer side is largely masked by the influence of the woofer cavity so the woofer side edge may stay hard.”

The shallow box also means it can be placed close to the rear wall with relatively short path lengths for wall reflections, which helps to maintain flat dispersion at low frequency in this position.

Finally, this shape is ideal for adding a subwoofer: just put it on the floor between the legs! That is an ideal place as it largely avoids low-frequency reflections on the floor between speaker and listener. The (separately available) subwoofer contains a high-power class D amplifier with a digital motional feedback loop. The system can be switched from two-way to three-way in the LS1 control software, which engages a second linear phase crossover so the phase coherency of the system stays perfect.

From the base model LS1a to the flagship LS1be with the beryllium tweeter, they all offer a fully integrated reproduction system. Although they accept both analog and digital inputs from any source, the ideal match would be the MU1.

Again (and yes it might get boring by repetition, but it is so important I mention it again), everything is under Grimm’s control, from music source to acoustic output. This tight integration between the speaker drivers, the amplifiers, the processing, and the power supplies is an invaluable opportunity to get it all working together for the best results. It allows them for instance to select drivers that you would not be able to use in a traditional passive system, but that offer additional degrees of freedom for optimization of the whole system. Don’t worry about having the right cable, or an amplifier with the right characteristics; get a MU1, an LS1 speaker and you’ll have one of the best audio reproduction systems that money can buy.

To give readers an idea of the length Grimm is willing to go to guarantee the best possible performance, consider the company’s calibration process. They developed an algorithm that simulates thousands of possible EQ combinations to achieve the “target curve” with the smallest amount of EQs and the least extreme settings for each individual speaker. The algorithm takes the acoustic sum of tweeter and woofer into account and aims for an “acoustic optimal fourth-order Linkwitz-Riley crossover” between the two. During the whole process an operator evaluates intermediate results and directs the algorithm. Computer-aided calibration is not only a time saver but often presents surprisingly minimalistic EQ settings with a better curve matching than even the most experienced operator would manually achieve.

Where Does Grimm Audio Go from Here?

I asked Guido Tent about future products. This is always a sensitive question, but he was willing to discuss two ideas. First, there will be a MU2 in Grimm’s future. Where the MU1 has strictly digital (AES or S/PDIF) outputs to interface with the LS1 series and other active systems, the MU2 will have its own internal DAC, and will interface with analog amplification and reproduction systems. With the MU1, Grimm can “control” everything up to the digital output connectors. The choice for internal upsampling and AES and S/PDIF outputs unburdens the downstream DAC from those tasks, but after that, it’s out of their hands. The coming MU2 will include a discrete DAC of their own design and output an analog signal, so this control will extend to the analog interface with analog (pre)amplifiers, eliminating DAC variables in the quest for the best possible sound.

Second, a phono preamp is in the making. As always, Grimm follows the theory: First think about what you are trying to do in a fundamental way. In this case, rethink the reproduction requirements for a phono signal. Many designs combine the lowest noise and lowest distortion circuitry they can come up with, coupled with the required RIAA correction.

But if you think about it in a fundamental way, you can question whether with vinyl you really need -120dB harmonic distortion and/or -100dB noise level. What other degrees of freedom does that give the designer to optimize the audio path for neutrality and “emotional reproduction”? Another adventure embarked upon, which will eventually lead to another potentially groundbreaking product.

After an extended listening session, which included a surround setup with five LS1s, we went to a local restaurant to continue our discussions on audio design and reproduction. A discussion that will never end, but to which Grimm intends to make significant contributions while building its dream! aX

Resources

[1] “Speakers White Paper,” Grimm Audio, June 2010,

www.grimmaudio.com/publications/speakers-white-paper

This article was originally published in audioXpress, July 2023