More than five years in development and after multiple iterations, Australian startup Nuheara achieved its goal with the Nuheara IQbuds2 MAX, a bridge toward truly smart hearables. The design uses digital technology to bring hearing aid functionality into true wireless earphones.

Prescription hearing aids typically cost thousands of dollars, but relatively inexpensive true wireless earphones often incorporate similar technology and hardware. On at least a fundamental level, all it takes to add hearing-aid functions to these earphones is an app and some firmware modifications. So it’s not surprising to see these functions appearing in new Apple earphones, or to see new companies emerge in an attempt to create a new class of products intended to augment hearing while providing great entertainment.

Nuheara is one of those companies, and the IQbuds2 MAX is its flagship product — a $399 set of true wireless earphones that tests the wearer’s hearing, applies a corrective response curve, and also adds such convenience features as active noise cancelling and IPX4 water resistance (Photo 1).

The IQbuds2 MAX webpage refers to the product as a “situational use hearing device,” and says that it’s not designed for all-day use as hearing aids are. Presumably, a hearing-impaired person would wear the IQbuds2 MAX to parties and restaurants to help with speech comprehension, and also use them for music, podcast listening, and TV watching, if the TV has a Bluetooth transmitter or an outboard transmitter is connected.

The earphones include an app that administers a hearing evaluation that Nuheara calls EarID. It’s based on the NAL-NL2 test, created by Australian Hearing’s National Acoustic Laboratories and licensed by HEARWorks. NAL-NL2 focuses on speech intelligibility. HEARWorks says the test is licensed by 18 different hearing aid and audiology equipment companies, and is used for more hearing aid fittings that any other test in the world.

The Product

The IQbuds2 MAX look a little bulky compared with most current true wireless earphones; physically, they’re more comparable to models that were sold three or four years ago (Photo 2). Each one contains a 9.2mm dynamic driver. The battery life is rated at 5 hours for streaming music and 8 hours for hearing assistance only. The included charging case provides three extra recharges.

In addition to the standard Bluetooth SBC codec, the IQbuds2 MAX includes aptX Low Latency, which could reduce lip-sync errors for TV viewing, depending on the latency of the display. To use the IQbuds2 MAX for TV viewing, you’ll need to add a Bluetooth transmitter. Nuheara offers the $99 IQstream TV transmitter, which is compatible with aptX Low Latency.

Each earphone incorporates three microphones. The multiple microphones facilitate several features, including active noise cancelling, focused listening, and phone conversations. The only controls are a single touch-sensitive button on the side of each earpiece.

Most of the power of the IQbuds2 MAX is in the smartphone app (Photo 3). In addition to accessing Ear ID, it also offers numerous listening modes. These mix between noise cancelling and hear-through mode (allowing external sound in through the microphones) and employ different types of filtering. There are seven basic modes: workout, street, home, office, restaurant, driving, and airplane. Four of these can be saved as favorites so you can select among them by touching the right earpiece. All can be altered to your liking using adjustments within the app. The app also enables the user to assign different functions to the controls on the left and right earpieces.

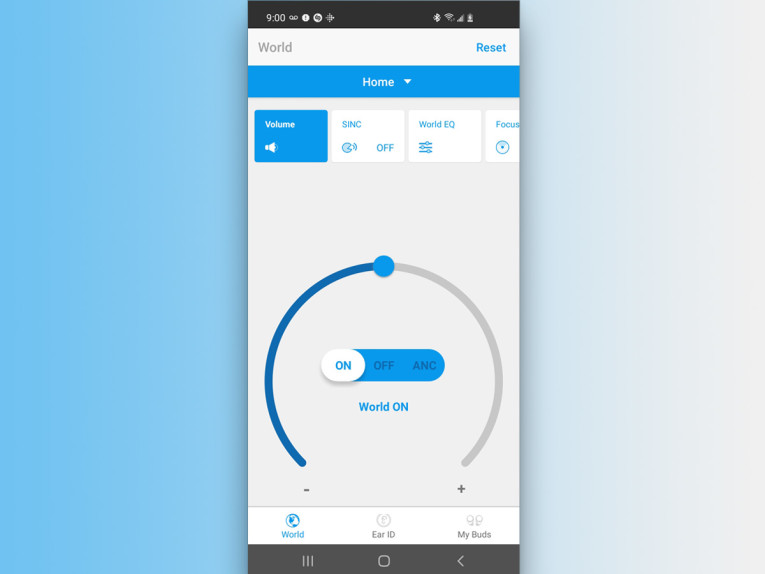

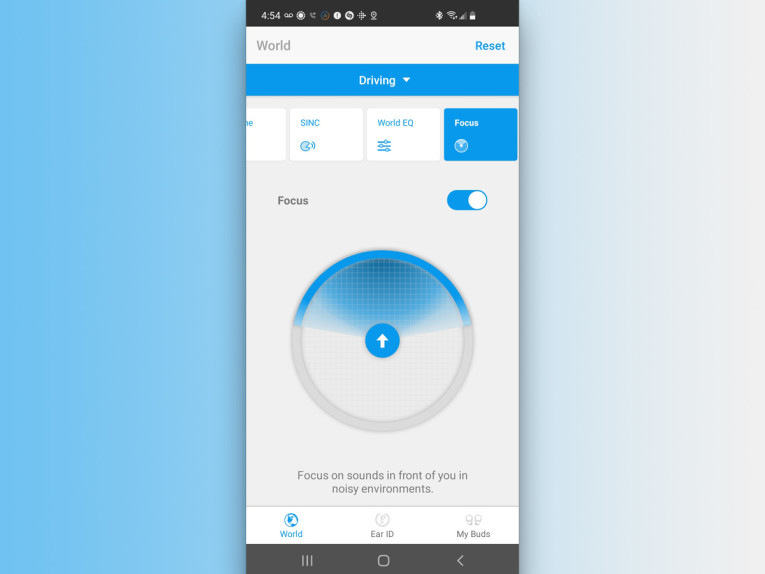

The adjustments are on four screens, three of which employ circular sliders. The one shown in Figure 1 turns noise cancelling on and off and activates the World mode, which allow a hearthrough function. Another, called Speech In Noise Control (SINC), mixes between allowing all ambient sounds in and focusing solely on speech. A World EQ screen adjusts the center frequency of the filtering of the World mode, from bass to treble. A fourth screen, shown in Figure 2, turns the Focus mode on and off; this one is non-adjustable. Surprisingly, there are no adjustments affecting the sound of the earphones themselves, other than turning Ear ID on and off.

The Hearing Test

My hearing loss —l ast tested by an audiologist in spring 2020 — is mild, and not something I notice on a day-to-day basis. In other words, about typical for a 59-year-old male. But it’s enough to show up on a hearing test, and I know the results well enough to know if results from an app-administered hearing test are in line with the results I’d get from an audiologist.

The test that Ear ID administers automatically is similar to an audiologist’s test in that it plays tones at six frequencies, from 500Hz to 6kHz, and asks you to tap an onscreen button when you hear the tone. It gradually decreases the level of each tone to find your hearing threshold for that frequency in each ear.

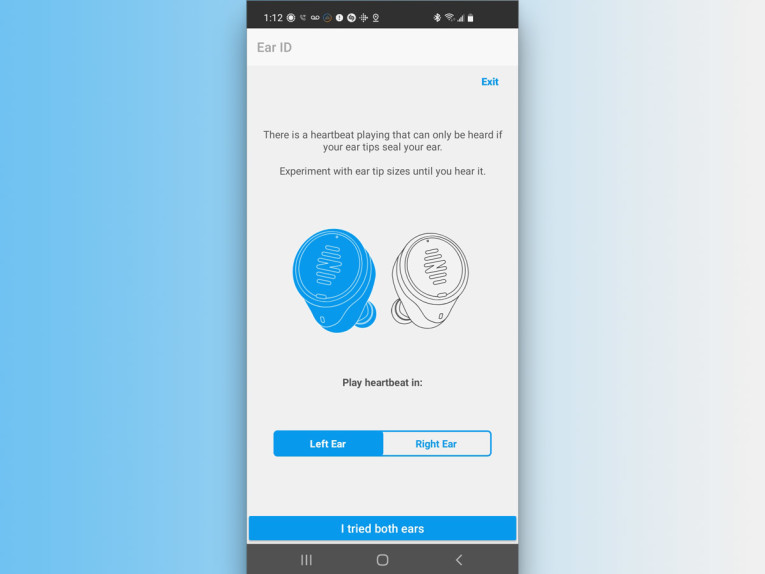

First, it “listens” to find out if the ambient sound level is low enough to allow an accurate test. Once that test is passed, it plays tones to see if the seal of the earphones in each ear is adequate (Figure 3). Then the actual test begins, and it takes about 3 minutes per ear. Once it’s completed, the app creates an Ear ID for you. You can retake the test again as often as you like.

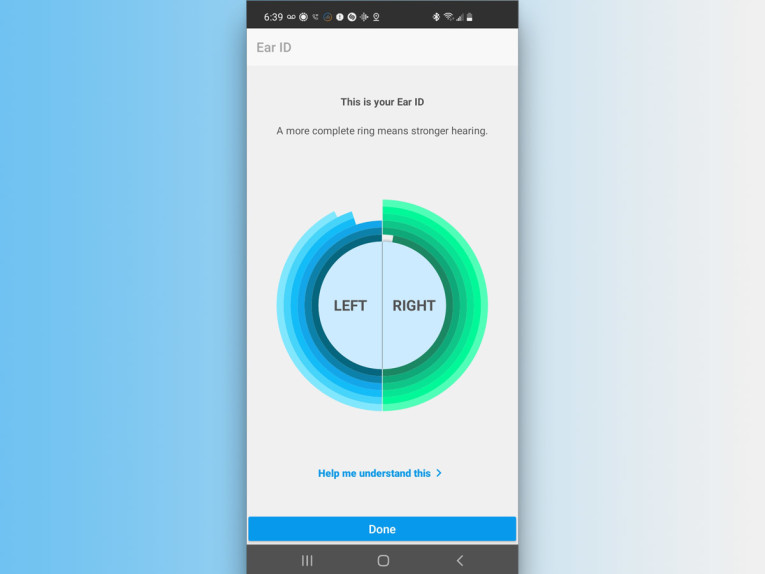

The chart the app provides is not as detailed or accurate as the test you’d get from an audiologist, but it was clear enough for me to get an idea of how it compares to the results from my audiologist’s evaluations. In the resulting chart, shown in Figure 4, the lighter the rings, the higher the frequency they represent. Ear ID correctly figured out that my right ear is better than my left. While there are no decibel markings on the chart, it seems to be saying that the loss in my left ear is mild at 3kHz and 4kHz, and a little worse in my right ear at 6kHz. It also says my right ear has no significant high-frequency hearing loss, but has a bit of low-frequency hearing loss in the 500Hz range. All of those results except the last one are consistent with my audiologist tests. I would guess that the earphone didn’t seal as well in my right ear canal as it did in the left ear, resulting in a bit of leakage and a reduction in bass response that the app interpreted as hearing loss. Unfortunately, my right ear canal is especially large, and sometimes even the largest tips supplied with earphones don’t seal completely.

Measurements

I performed measurements using GRAS Sound & Vibration test equipment: the Model 43AG, an RA0402 high-resolution ear simulator/coupler, and an M-Audio Mobile Pre USB interface with TrueAudio TrueRTA real-time analyzer software (Photo 4).

Because the IQbuds2 MAX wouldn’t pair with the Mpow BH259A transmitter I use for measuring Bluetooth headphones, I couldn’t use my usual Audiomatica CLIO 12 analyzer, and I had to rely on test signals generated by the AudioTool Android app in my Samsung Galaxy S10 phone.

Like many higher-end earphones, the IQbuds2 MAX mute themselves when they’re removed from the ear, so they have to be “tricked” into working when placed in an ear simulator. Typically, earphones detect whether they’re in the ear using a light sensor, which is easy to fool with a tiny wad of poster adhesive. But the IQbuds2 MAX also have another sensor, perhaps an orientation sensor or a way to sense the proximity of the other earpiece.

The only way I could figure out to defeat the second sensor was to hold the ear simulator up next to my ear and transfer the earphone gently from my ear into the ear simulator. To say the least, this complicated my measurements even further. I started with the most basic of measurements for earphones: frequency response.

In this case, I measured the IQbuds2 MAX 1/12-octave-smoothed frequency response with Ear ID off, so I’d be measuring the “native” response of the driver and whatever DSP tuning Nuheara provides as a default. You can see in Figure 5, which compares the IQbuds2 MAX with two conventional true wireless earphones (the JBL Club Pro+ and the Status Audio Between Pro), that there’s nothing unusual about the acoustical design of the IQbuds2 MAX. So that suggests these should be pretty good earphones for listening to music, with or without Ear ID.

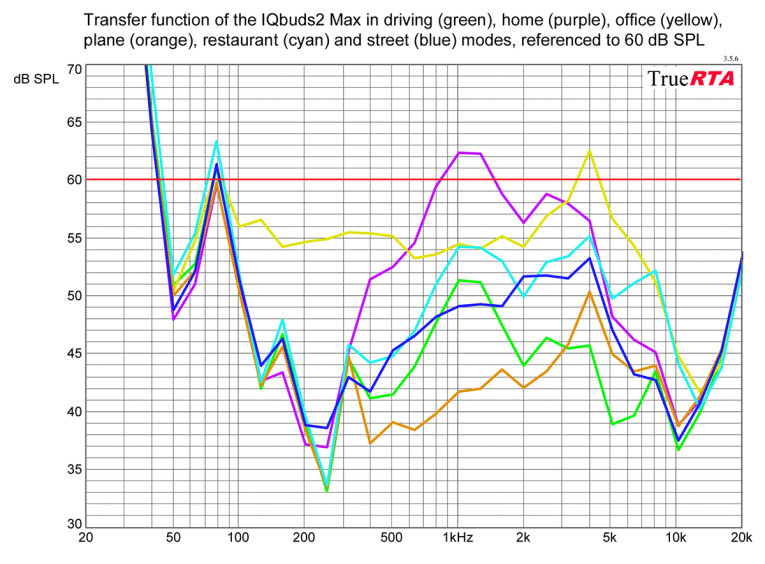

To test the hearing-assistance functions, I used an array of six Dayton Audio B652 speakers mounted around my lab plus a Sunfire True Subwoofer Jr., all playing uncorrelated pink noise at 60dBC. This is the same procedure I use to test noise cancelling in headphones and earphones, but at a noise level 25dB lower. Figure 6 shows how the different hearing-assistance modes filter the sound. The 60dB baseline (corrected for the response of the speakers, room and ear/cheek simulator) is shown in red. (Note that TrueRTA displays traces in only six different colors, so I had to leave out the Workout mode.)

The Office, Plane, and Street modes emphasize 4kHz (presumably to improve speech recognition), while the home and driving modes emphasize 1kHz (for reasons I can’t guess). Restaurant mode is more of a broadband boost between 1kHz and 5kHz. Of course, most of these modes are just an estimation of what kind of emphasis you might need in these environments, because from an ambient noise standpoint, offices, restaurants, and streets, for example, can differ quite a bit. But at least the user has a variety of emphasis profiles easily available.

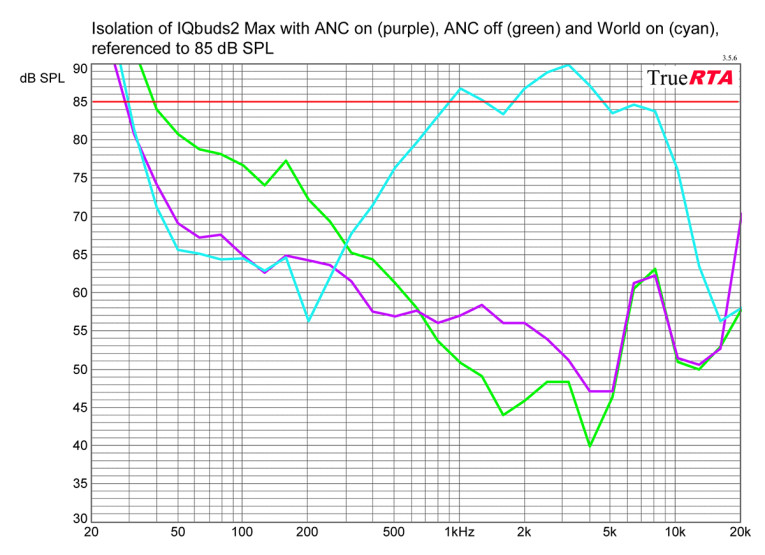

I also measured the effects of the noise cancelling feature, which you can see in Figure 7. I measured these curves the same way I did for the previously mentioned modes, but at my usual baseline of 85dBC pink noise for noise-cancelling measurements. I used the switch on the screen from Figure 1, flicking among the ANC on, ANC off, and World modes (with World EQ centered).

The noise cancelling is fairly effective, reducing low-frequency sounds (where most jet airliner cabin noise resides) by about -20dB. The World mode, with the EQ centered, admits a broad band of sound between about 700Hz and 9kHz, which should be plenty to permit good speech comprehension.

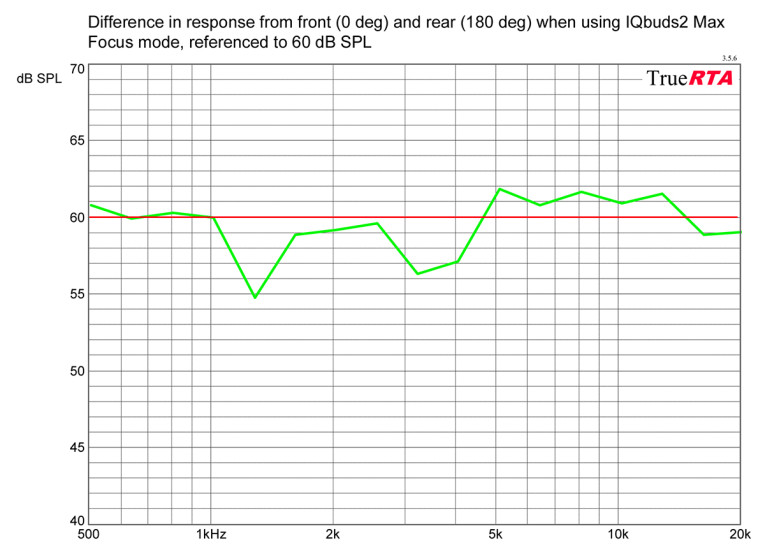

Measuring the effect of the Focus control was complicated for the reasons cited earlier. I employed much the same method I did when testing the directional function of the Widex Moment hearing aids, with the earphones positioned between one Audioengine HD3 speaker in front and another one in back. But I had to sit between the speakers and hold the ear simulator up to my ear. Regardless, it did seem to work. I ran measurements of the differences in response from front and rear with the Focus mode turned on and off, subtracted the rear response from the front response in both cases, and then subtracted the difference with Focus on from the difference with Focus off. You can see the results in Figure 8.

Focus mode does seem to reduce the response from the rear by -1dB to -5dB in a band between 1kHz and 4kHz, which is where the strongest directional cues occur. This mirrored my results when using the IQbuds2 MAX. I found that Focus mode had an audible but mild effect, probably enough to make a modest difference when conversing in a loud restaurant.

Subjective Testing

As I wrote this, the coronavirus pandemic was starting to wind down, but I wasn’t yet traveling or interacting with people face-to-face on a regular basis. However, I was able to use the IQbuds2 MAX when shopping, walking the dog, and for music listening and TV watching. The app made it easy for me to try evaluating the sound in different environments and hear the effects on speech and ambient sounds.

Despite the bulky design, I found the IQbuds2 MAX earphones easy to fit into my ears, and comfortable to wear. It helps that they come with six different sets of eartips: three sizes each in foam and silicone (Photo 5).

With the Ear ID correction activated, I heard a slight high-frequency boost that, to my ears, improved the sound of music and podcasts just a bit. The earphones still sounded good without Ear ID, although I’d describe their native, non-Ear ID tuning as slightly on the soft side, with a somewhat mellow treble. I did most of my listening with Ear ID on, which is a good sign — I’ve tried some hearing test and augmentation apps that made the sound excessively shrill and unenjoyable. Overall, I’d say that with Ear ID on, the IQbuds2 MAX are competitive with typical good-quality earphones priced in the low three figures.

While I didn’t have access to places that would be suitable for testing the office, restaurant, and plane sound enhancement modes, I was able to try the various modes in my wanderings around Los Angeles, CA — from going to the grocery store and the music store, to walking my dog, to chatting with socially distanced neighbors at the park. Being able to preset four modes for quick access was a big help. I often started out my journeys fussing with the controls in the app, but lost interest because usually I could get the response I wanted simply by selecting the most suitable mode by tapping the right-side earpiece.

This is an important point — many of the people within the demographics who most often experience hearing loss are not inclined to open a smartphone app to do much of anything, much less fuss with a bunch of settings for their earphones. The way the IQbuds2 MAX setup works, a tech-savvy relative can help the wearer set up the earphones, and all the wearer really needs to do after that is touch the right-side earpiece to access the different modes.

I found that initially the enhancement modes could sound unnatural because they tended to amplify and exaggerate certain sounds — for example, walking through the parking lot to the grocery store, I was bothered by a “whooshing” sound I’d never noticed before, which I later realized was road noise from the nearby freeway that my brain had long ago learned to tune out from my non-augmented ears.

When I went into the store, the whooshing disappeared, but I had heightened awareness of all the little sounds around me, such as people crinkling plastic bags, grocery cart wheels squeaking, and all the little bleeps and bloops that the various machines in the store emit. But after about 10 minutes of shopping, I realized I’d completely forgotten I was wearing the earphones.

The IQbuds2 MAX did a great job of amplifying not only voices, but alert sounds. The best example I can cite is that when in Driving mode, the IQbuds2 MAX seemed to make the clicking sound of the turn signal about 6dB louder, to the point where there was no way I could forget the signal was on. If the IQbuds2 MAX can deter even just a few drivers from obliviously leaving their blinker on as they drive down the road, Nuheara will have made the world a better place.

The only time the IQbuds2 MAX disappointed me was when I kept hearing a distorted, crackling sound in my left ear as I was driving. I thought perhaps a feedback or feed-forward circuit in the earphones’ active noise cancelling was being driven into clipping, as often happens in a jet airliner during takeoff when the engines are running at full rated power and cabin noise is at its max.

But I later realized the problem was wind noise caused by the air current from my car’s ventilation system. If possible, it’d be nice to add a wind noise cancellation algorithm to these earphones, like the algorithm used in my Jabra Elite Sport 65t earphones.

Conclusion

According to the World Health Organization, hearing loss sufferers are expected to nearly double in number by 2050. Yet the average $2,300 per ear that one has to spend on traditional hearing aids purchased through an audiologist is clearly out of reach for many people. While people with severe hearing loss obviously need to consult health professionals for solutions tailored to their problem, people who just have difficulty understanding conversation in noisy restaurants would benefit from a less costly solution like the IQbuds2 MAX.

From my experience with the IQbuds2 MAX, I think it has the power to provide a significant and welcome improvement in speech comprehension, and it’s a good-sounding set of noise-cancelling earphones to boot. People who have a mild but troublesome degree of hearing loss can pick these up (at a discount) from online merchants, spend half an hour figuring out how they work and taking the Ear ID test, and potentially get a significant quality-of-life improvement. Even if they don’t, they’ll still have a nice set of noise-cancelling earphones, at only a small price premium compared to what they’d pay for noise-cancelling earphones from the big consumer brands.

I’ve already started telling my friends who have hearing loss about the IQbuds2 MAX; they’re all intrigued, and I expect several will buy a set. Clearly, this is a product that fills an all-too-common need. aX

This article was originally published in audioXpress, July 2021

About the Author

About the AuthorBrent Butterworth has worked as an audio journalist and technical consultant since 1989. He currently writes for Wirecutter, SoundStage, and JazzTimes, and has published speaker, headphone, and amplifier measurements in audioXpress, Sound & Vision, Home Theater, Home Theater Review, and many other publications. He has also served as a consultant on measurement, design, and tuning of audio products, with a special focus on active speakers and DSP tuning.