But it’s not the full experience. That’s fine for listening while cooking or driving, but not for system calibration, and not for an old-fashion listening session. This is where hi-res streaming enters the conversation. Now you don’t have to choose: You can have the convenience of streaming, as well the quality of lossless CD audio and higher, using one of two services.

High-Resolution Streaming

You’re probably familiar with Tidal: the streaming company that made a splash in the audio community in 2014 when it brought lossless CD-quality streaming to the US, UK, and Canada. Enthusiasts were again pleased when Tidal announced in 2017 that it would begin streaming hi-res audio. But there’s another contender that you might not have heard much about: Qobuz. The Paris, France-based company aims to outclass all the other streaming services on three fronts: sound quality, documentation, and editorial content.

I recently chatted with Dan Mackta, Managing Director of Qobuz US. On the company’s history, Mackta said, “Qobuz was started in France in 2007 as a hi-res download store by classical music fanatics. They felt that serious music fans were not being addressed in the online music space.” And in the intervening years, “it evolved into a full-service, all-genre streaming service.”

Though it was founded a full seven years before Tidal, Qobuz may not have reached your ears because it was initially focused on Europe. But that changes in 2019 with an expansion to North American shores. Some consider this a dangerous move: German company HighResAudio said that it considered expanding to the US, but opted not to because of music licensing fees. “None of the exciting streaming service[s] are profitable ... it’s a huge loss. So, why would anyone try to enter the US market, especially operating it from Europe?” HighResAudio is not wrong.

Spotify has never had a profitable year since it was founded in 2006. And Tidal, the only hi-res streaming service in the US until Qobuz’s 2019 launch, is in a pattern of losing tens of millions each year.

I spoke at length about this with David Solomon, the Chief Hi-Res Music Evangelist of Qobuz. Solomon said, ”Our big plan is we’re going to augment our profitability with downloads promoting the audio industry, which will promote us back, and then promoting artists who will promote back. [We’re] doing a whole bunch of stuff now that’s never been done before.” It should be noted that the US has never had a hi-res streaming service primarily marketed to audiophiles.

And Qobuz has plans to outdo Tidal. When I asked Mackta about what makes Qobuz different, he reiterated the three advertised strengths of Qobuz: “The largest available library of streaming hi-res music, focus on quality of metadata, and context.”

The Qobuz Difference

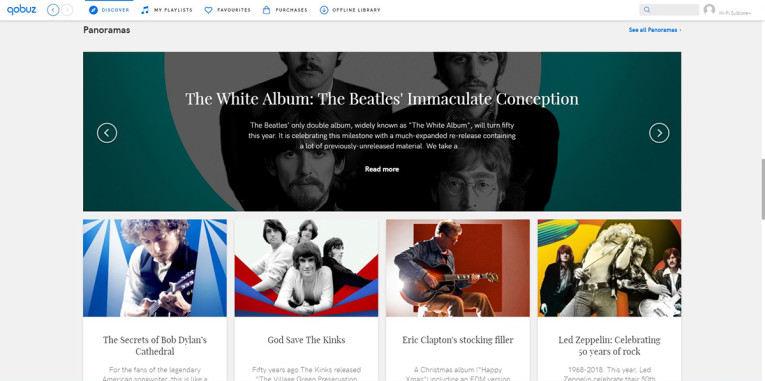

Let’s briefly explore those three areas of improved service. For sound quality, Qobuz believes in delivering music to your ears in the highest resolution possible. For much music, that is CD quality at 44.1 kHz/16-bit. Beyond CD quality, you can find 24-bit music in its catalog, including higher sample rates of 96 kHz and 192 kHz, as heard in the studio. Qobuz emphasizes discovering and cleaning up metadata, and filling in the story of how a piece of music came to be and which people made it happen. Additionally, Qobuz includes digital booklets for millions of albums in its catalog, showcasing lyrics and additional art, as carefully created by the artist. And for editorial content, the staff at Qobuz puts together articles dubbed Panoramas as an exploration into artists fundamental to shaping their genres (see Figure 1).

The first Panorama was published in late 2016, exploring the music and cultural significance of The Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds. Since then, new Qobuz Panoramas have appeared almost weekly, delving into the history of legendary conductors, the fusion of afrobeat, the shaping of 90’s British shoegaze rock, and the telling of film compositions in the making. Panoramas generally include music videos and mini-documentaries, and a handpicked list of songs that demonstrate the styles and forms laid out in the article. As compelling as these benefits seem, Qobuz is certainly in a crowded marketplace.

Let’s take a look at the other players.

The Competition

The typical streaming services are difficult to differentiate: Spotify, Google Music, and Apple Music all offer individual plans for playing unlimited, ad-free music for $9.99/month and family accounts for $14.99/month. Streamed music is typically 320 kbps, considered high quality for lossy streaming. These services each have catalogs with more than 40 million songs, each offer algorithm-generated radio stations off of artists and playlists, and each offer downloads for offline listening.

Deezer offers similar features and solo/family plans with the addition of Deezer HiFi, its $19.99/month service to stream full CD-quality music in a lossless format. Qobuz matches Deezer’s service tiers and pricing, and then some, with Qobuz Premium providing 320 kbps MP3 for $9.99/month, Qobuz Hi-Fi offering 44.1 kHz/16-bit FLAC streaming for $19.99/month, and Qobuz Studio unlocking hi-res FLAC streaming up to 192 kHz/24-bit for $24.99/month. Each tier can be purchased annually at the cost of 10 months instead of 12. And the final tier, titled Qobuz Sublime+ at $299.99/year, includes the 192 kHz streaming of the Studio tier as well as discounts in its download store, reportedly 40% to 60% off.

Qobuz streaming is available via its web player and dedicated apps for Windows, macOS, iOS, Android, and Kindle. For those in the US, the only option for hi-res streaming above 44.1 kHz has been Tidal, stepping up from its lossy 320 kbps AAC streaming at $9.99/month to Tidal HiFi at $19.99/month. This service tier includes music at higher sample rates and bit depths delivered via an MQA stream.

Opting Out of MQA

MQA is short for Master Quality Authenticated, a sort of assurance to the listener that the content being delivered is the highest quality available. MQA is able to “fold” higher sample rate audio, significantly cutting down on file size. The result is a file that can be unfolded to a higher-res file by the right software and hardware. MQA is technically lossless compression that some experts believe comes with audible consequences, and many in the audio industry are hesitant to opt-in, viewing the licensing of MQA as giving too much power to one company, causing the cost of all music and audio equipment to increase.

For better or worse, Qobuz does not rely on MQA. I probed on this point: a man of few words, Mackta simply stated, “If customers demand it, we will consider it.” Solomon added, “I have zero issues with MQA. I think it sounds good. [But FLAC] is just the way it’s always been done. It’s easy. You don’t have to go through any steps to unfold this or fold that.”

Forgoing MQA, the Qobuz approach to hi-res is about transparency and quantity. With Tidal, each hi-res album is merely branded “Master,” and whether Master in each particular case means a purist 192 kHz/24-bit or a paltry 44.1 kHz/24-bit, there’s no way to be sure. Qobuz, on the other hand, marks the sample rate and bit depth of every album. As for quantity, Qobuz already has double Tidal’s number of hi-res tracks, and that number increases almost daily. Qobuz also makes it easier to stream hi-res music. You can stream 192 kHz through the Qobuz desktop app, the mobile app, and even the web player with no additional hardware or software required. Meanwhile, Tidal restricts its streams to 96 kHz using the desktop and Android apps, with a 44.1 kHz limit for iOS and the Tidal web player. The only way to get 192 kHz out of Tidal is through the use of an MQA-capable DAC.

The Bandwidth of High Resolution

You pay heavily for the convenience of Qobuz with bandwidth, however. Streaming an album at 192 kHz uses about 42 megabytes of bandwidth per minute of audio. And halving the sample rate to 96 kHz still requires 23 megabytes per minute.

Qobuz Data Tier Bandwidth per Minute:

192 kHz/24-bit — FLAC — 41.9 MB

96 kHz/24-bit — FLAC — 23.4 MB

44.1 kHz/16-bit — FLAC — 8.0 MB

320 Kbps — MP3 — 2.5 MB

Total Bandwidth per minute by Quality Tier:

Master — MQA — 12.9 MB

44.1 kHz FLAC 6.8 MB

320 KBPS — AAC — 2.6 MB

96 Kbps — AAC+ — 0.8 MB

The numbers are intimidating. Streaming 192 kHz audio on 4G LTE, I’d chew through my monthly 2 gigabyte data bucket in less than an hour. And with daily hi-res streaming added into a month’s worth of downloads, cloud backups, and a whole household’s video streaming: data overage charges could become a regular occurrence even at home. But Qobuz is looking to the future: “Space is getting cheaper and bandwidth is just absolutely multiplying,” Solomon said. “Bandwidth is wide enough that nobody has any problems streaming stuff. 5G is coming in about 10 minutes. A gig up, a gig down, that’s gonna be the basic plan that’s selling for $30/month.”

Judging Streaming Services

We’ve looked at sample rates and bandwidth, but how does Qobuz sound? In a word, excellent. Listening on my powerful home system in a treated room, I’m very pleased with the sound. To be fair, Tidal also sounds excellent. Can one differentiate between sample rates? I believe yes, and it’s easiest when looking for specific cues in the audio. But these are small differences for the enthusiast, not the casual listener.

However, there’s more to like or dislike about a streaming service than the raw quality of its files. App functionality and ease of use are important. Music discovery plays a big role to many. And we haven’t yet explored Qobuz’s claim to improved metadata. I would traditionally include depth of catalog in any streaming service review, but the good folks at Qobuz thoroughly stressed that Qobuz US was still lacking a significant portion of its catalog in the beta version I reviewed. Eric Benoit, the Marketing and Operations Manager at Qobuz US, assured me that many missing albums were still being populated. Qobuz in Europe offers more than 40 million songs in its catalog, and I would expect nothing less from Qobuz US now that the beta status has officially been lifted.

The Desktop Interface

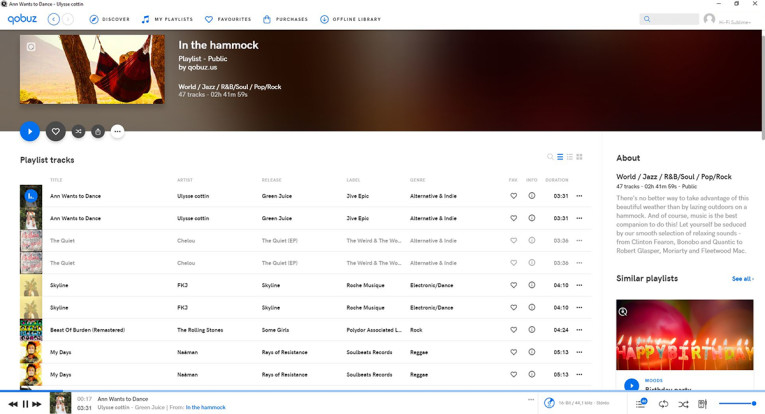

The Qobuz interface for desktop and web player is laid out in four tabs: Discover, My Playlists, Favorites, and Purchases. Discover consists of a genre filter, music newly added to Qobuz, curated playlists, and Panoramas (see Figure 2). My Playlists functions as you’d expect. And Favorites houses all the music for which you’ve clicked the heart icon.

The Qobuz desktop app adds a fifth tab for Offline Library. Any music throughout the Qobuz catalog can be downloaded, a convenient feature for those traveling. While expected for mobile, Qobuz is unique in offering downloads on the desktop. It’s worth noting a few Frenchisms that remain in the Qobuz interface at the time of review. For example, Qobuz metadata lists the “Composeur” of each album, and the quality of a current stream may be listed as “16-Bit/44,1 kHz - Stéréo”. Also, the application measures used storage in Mo and Go, not MB and GB.

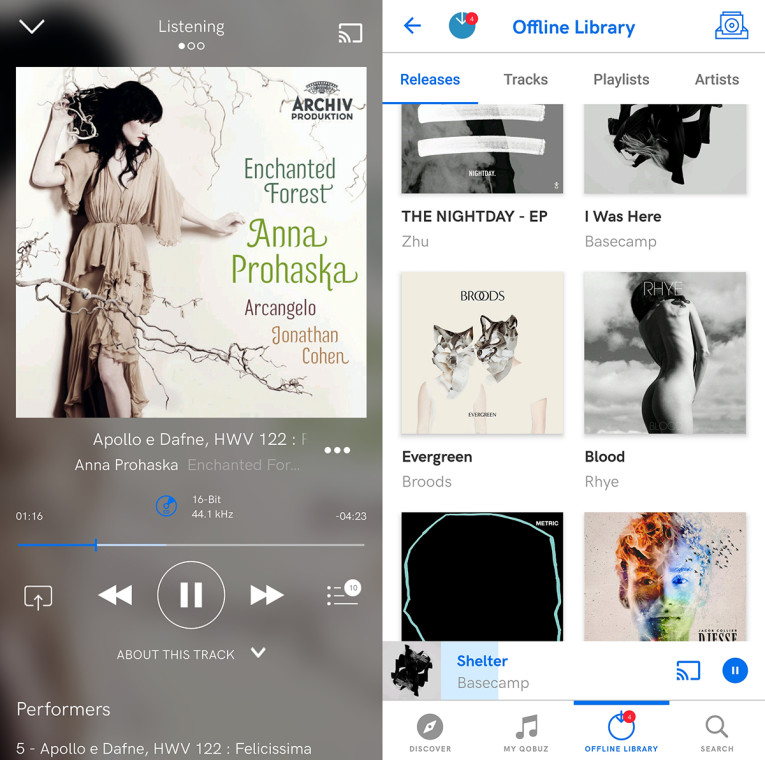

The Mobile Interface

The mobile app has a lovely simplicity to it. The bottom always-visible menu has four tabs for Discovery, My Qobuz, Offline Library, and Search. Discovery is laid out just as on the desktop app, and My Qobuz contains subpages for My Playlists, Favorites, Purchases, and the app settings. And the Offline Library tab has a download animation while downloads are active, as well as a number indicating how many remaining tracks are queued to be downloaded. I especially like the interface for showing what’s currently playing: a tab called Listening with album cover art, file quality, playback controls, and track metadata. A quick swipe to the left shows all tracks queued to play, and another swipe left shows a history of tracks played regardless of play queue (see Figure 3).

The Nitty Gritty

Playback quality is governed by the maximum you choose (see Figure 4). On mobile, you have the ability to set separate quality caps for streaming on Wi-Fi and mobile networks. In the desktop app settings, you have the option to take exclusive control of the selected audio device. Using exclusive control, I watched my DAC display its automatic switch to different sample rates as I played different tracks, barring Windows Core Audio from resampling my Qobuz stream. The mobile app does not cache audio more than a handful of seconds in advance, but the desktop app caches the entire track at once.

The caching is a nice feature because it visibly builds your offline library if you check an option in the app’s settings, adding all cached tracks to the offline library. You’d be right to be concerned about Qobuz monopolizing your storage space as it automatically caches all music played. Under music playback settings, you can set the maximum cache size from 500 MB to 100 GB. As a bonus to those with multiple hard drives, Qobuz allows you to set a new location for cached music to reside. The music download location can also be changed in the settings, and you can monitor how much space it is using.

Qobuz also supports linking to Facebook and Last FM, in case you want the world to know which music and Qobuz articles have been occupying your time. Qobuz lists keyboard shortcuts to better navigate the interface, control playback, and adjust streaming quality on the fly. And there’s even the option to route your stream through a proxy.

Third-Party Support

In addition to its native software apps, Qobuz has partnered with a number of other companies to make its streaming available to more devices in more homes. By my count, 39 different hardware manufacturers from consumer to hi-fi support Qobuz hi-res streaming. Also, Qobuz supports software streaming through specialized playback programs, including Amarra Luxe, Audirvana Plus, and Roon. I asked Solomon about the benefit of these programs, and he said, “You can make almost anything play bit-perfect if you really know what you’re doing, if you disable all the Windows crap that happens in between the signal and your DAC; all the Mac crap that happens in between the signal and your DAC. All of that is removed with the use of [these] specialized programs.”

I explored Qobuz through Audirvana Plus with good results. Hi-res albums are marked in the interface, and I found album reviews by Qobuz staff and even my favorite albums marked in Audirvana (see Figure 5). However, Qobuz’s extra metadata was not visible. I also explored Qobuz through Roon. Roon has a lot of unique features it adds beyond acting as a portal to Qobuz: It has a unified search for music that shows both Qobuz and Tidal results together, and songs from both services can exist in the same playlist. Additionally, it acts as a music hub for your other stereos and devices. At $119 annually, Roon adds a lot of functionality to Qobuz that might be considered irrelevant to some and mandatory for others. Qobuz streamed just fine to my Chromecast Audio up to 96 kHz. In addition to Google Cast, Qobuz supports MusicCast, AirPlay, and Bluetooth.

Usability

Both the desktop and mobile Qobuz apps have excellent ease of use. Features are laid out intelligently, and extended metadata is easy to access. I compared latency streaming 320 kbps as an even benchmark across services. Loading a new track in Qobuz takes on average 1,25 to 1,5 seconds. This feels noticeably latent compared to other services, with Tidal and Google Music consistently loading new tracks in one quarter to half a second. The latency is also felt in the interface, where it typically takes three full seconds to load an artist page. Mackta said, “Right now, AWS (Amazon Web Services) hosts and serves Qobuz to consumers around the world.”

Whether the fault lies in hosting or optimization, at least for now, Qobuz feels more latent than Tidal and Google Music. The search functionality in Qobuz is generally robust, though there are a few hiccups. When searching for “Clapton,” Qobuz first recommends the artist Clapton with 0 albums and a description matching Eric Clapton. The second result is for the artist Eric Clapton with 172 albums and a different description of the same man. Tidal and Google Music don’t have this confusion. The Qobuz search is intelligent enough to show the artist P!nk when searching for “pink,” listed before Pink Floyd, yet after the artist White Noise Meditation, Pink Noise, Zen Meditation, and Natural White Noise and New Age Deep Massage. Neither Tidal nor Google Music get hung up on the meditation “artist.”

Art and Metadata

In Qobuz, album art is always 600 × 600 pixels. This feels small compared to Tidal’s 1280 × 1280 pixel album art, but fine in comparison to Google Music at 512 × 512 pixels. Depending on the album, Tidal has the obvious advantage of resolution. But for other albums, Qobuz or even Google Music appear sharpest. After all, the largest stored image means nothing if it was scaled up from the smallest source. Overall, there is no clear winner for album art quality (see Figure 6).

Qobuz and Tidal both have pretty deep liner notes for each and every song. However, Tidal also includes liner notes per album, which Qobuz doesn’t. Further, Tidal includes links to featured musicians’ artist pages, making it easy to tell when a guest horn player on a song is also an artist in his own right with albums of music to explore. Tidal and Qobuz sometimes have a review next to an album, sometimes not. The presence of a review on both can be hit or miss, even on major releases. Both Qobuz and Tidal can be subject to the same minor metadata mistakes, perhaps missing one of several backup singers in a song. Both Tidal and Qobuz seem beholden to the same sometimes-obscured information (e.g., guitarist vs. participant). Google Music’s approach, by comparison, offers generally more complete and accurate information by relying on the crowd-sourced input of Wikipedia, visible with a single additional click.

Qobuz seems subject to additional metadata mistakes, however. For example, though Qobuz has deep liner notes for Evanescence’s album Synthesis Live, the name for each song is followed by “(Live) (Live)”. Google Music and Tidal don’t share this redundancy. Similarly, for the new album “boygenius,” Qobuz lists each track with “[HD]” after the name, though the music is standard CD quality. Again, Tidal and Google Music display the song names without the tag. And artist Sara K., though listed properly in Google Music and Tidal, shows as K. Sara in Qobuz.

In my testing, I didn’t notice any examples of Qobuz having more accurate song titles than the competition. Mackta of Qobuz shared, “The metadata is initially delivered along with the music and artwork by the record label or rights-holder. When errors are brought to our attention, we can manually make fixes. In addition, we are partnered with several third-parties to enhance the metadata and information we are able to provide.”

As for digital booklets, Qobuz claims there are millions in its catalog. Yet, despite opening some 300 albums in Qobuz, less than 10 had digital booklets. When pressed on this topic by a user in a “Hello Qobuz!” Q&A session, Qobuz responded: “It has been 6 years now that we have fought, there is no other word for it, with publishers and distributors to ensure that [digital booklets] are delivered to us. But if many are still missing, this is not our fault. If you only knew the time that we spend chasing this up!”

And that was back in 2015. Judging by its press release claims over time, Qobuz is having success in finding and adding booklets. But it comes across more as a pleasant surprise for some albums than a feature across most albums (see Figure 7). Overall, Qobuz comes up short in metadata, especially considering Tidal prides itself on exclusive releases and music videos, not metadata. But this trend may reverse given more time.

Music Discovery

In addition to the superb Panoramas I described earlier, Qobuz leverages its Ideal Discography and Qobuzissime awards to draw attention to significant historical albums and unique albums by emerging artists. Qobuz awarded albums are recognized in a special place, and most have original reviews by Qobuz staff. If you’re after an education in musical history, Qobuz has a lot to share.

However, there’s also the dark side of artist discovery on Qobuz: There’s no form of algorithm-generated radio whatsoever. And this is important because, for many listeners, algorithm-generated radio is the single best way to find new artists. Broad categories are fine for those merely after “classical” or “blues,” but it doesn’t offer much for those after more specific or obscure genres. My personal listening tastes continue to evolve to more niche subgenres, guided by Google Music’s superb radio algorithm. This just isn’t possible in Qobuz.

Tidal offers limited algorithm-generated radio with mixed results, but Qobuz’s complete lack of radio feels even more claustrophobic: Sure, the catalog is large, but it’s lost to you if you don’t know specifically what to search for. Fortunately, Qobuz has confirmed that algorithm-generated radio is “on the roadmap,” but there’s no telling of when it will be released or how effective it will be. Furthering the artist discovery problem, recommended artists in Qobuz are weak, and recommended albums are worse. Some of the suggestions couldn’t be more wrong, tying Fleetwood Mac and a choral album as recommended listening to the electro-pop artist Broods. And when listening to an album by pop star P!nk, my first two suggestions are for a German folk/orchestral cross-over album and a jazz crooner singing Christmas songs.

Beyond custom radio, Google Music has well over a thousand pre-made stations spanning diverse subgenres, allowing you to dial into specific styles even if you’ve never heard of them before, and each playlist feels bottomless. By comparison, Qobuz includes a few curated playlists, but the playlists are short, sound scattered, and seem entirely dependent on a listener’s tastes. I’m left with the distinct impression that Qobuz is not currently fit for assisting in artist discovery. It hasn’t bridged me to a single new artist that I’m interested in exploring (see Figure 8).

Analysis of Files

Qobuz assured me that the quality of its stream is identical to the quality of its purchased downloads. I put that to the test with a 192 kHz file from the Qobuz download store and the same file streamed and captured at 192 kHz. MusicScope by Xivero, an excellent tool for learning more about your audio files, confirmed that both files contained the full 24-bits of data, and that there is high-frequency content north of 45 kHz that wouldn’t exist in a file upscaled from a CD-quality source. A null test confirmed that the Qobuz download and stream sound the same (see Figure 9).

The State of High-Resolution Streaming

Let’s take a step back. Tidal has more than 1 million hi-res tracks available for streaming, but it masks what hi-res means for each track. And we have Qobuz with more than 2 million hi-res tracks, though many are barely hi-res at 44.1 kHz/24-bit. And the vast majority of each’s catalog remains CD quality.

One might come to the conclusion that hi-res music just isn’t that available. I’ve heard speculation that music license holders fear unlocking the possibility for hi-res music piracy. No one can deny that capturing the audio output of a computer is easy, but Qobuz isn’t concerned. “If you look at piracy numbers, say 10 years ago and now, they’re almost at zero,” Solomon said. “It’s still going on — I’m not naive. But the numbers suggest that people almost totally lost interest, at least in music piracy, because [music is] so available.” Tidal has many hi-res albums that Qobuz doesn’t, and Qobuz has many hi-res albums that Tidal doesn’t. But overall, hi-res availability is growing.

Solomon added, “It’s all about ingestion. If you look at our site now, and then you look at it in a month, there will be another 25,000 cuts on there. Yesterday, we just signed a deal with Channel Classics, and now we’ve got the whole Channel Classics collection in hi-res on Qobuz that we didn’t have the day before.” I asked Solomon if Qobuz is working harder than Tidal at growing its hi-res library. He said, “We’ve got two million and they’ve got one million, and we’re just starting. If you’re only going to have one service and you’re truly into hi-res, we’re the only game in town. You’ll never be able to catch up with us because we just keep adding whole catalogs. We’re about to add Blue Coast [Records]. Nobody’s got Blue Coast. The only way you’ve ever been able to get Blue Coast is to buy them, and we’re gonna be streaming them.”

The Value Proposition

We’ve explored the positives and the negatives of Qobuz. Its metadata needs work, the interface feels sluggish, and Qobuz has dubious skill in pointing you to new music. But where Qobuz excels is sound quality, hosting the largest hi-res streaming library available, and the added bonus of a music history curriculum for those who choose to explore it. I see one target audience that values these features above others: the audiophile. Fortunately, Qobuz already has this group in its sights. When I asked about Qobuz’s future plans, Mackta said the goal is to “gain widespread adoption of the streaming service by the audiophile community in the US and grow from there.“

I don’t see Qobuz offering value with its $9.99/month service tier. It lacks the algorithm-generated radio of its competitors, and it offers no fringe benefits, like Google Music’s ad-free YouTube inclusion, or Spotify’s Hulu inclusion. Qobuz’s $19.99 plan merely ties Deezer with audio quality, and for the same price, Tidal offers hi-res. It isn’t until the $24.99/month Qobuz Studio tier that the value begins to make sense. This service offers twice as many hi-res tracks as Tidal, and these tracks are delivered to more devices, with transparency on the files being streamed. This is exactly what hi-res streaming has been missing. Given time, I expect its metadata to improve and its curated playlists to expand.

Properly implemented algorithm-generated radio could completely overturn Qobuz’s music discovery limitations. And the company has demonstrated a thirst for collecting hi-res music as Qobuz aims to set itself apart from Tidal. Even in its current state, I believe Qobuz to be the best option for the audiophile who knows what he wants to listen to and cares more for playback quality than any other aspect a streaming service offers. aX

This article was originally published in audioXpress, April 2019.

Resources

www.qobuz.com

J. Martins, “Master Quality Authenticated (MQA): Redefining the Source for Music,” audioXpress, June 2016, https://www.audioxpress.com/article/master-quality-authenticated-mqa-redefining-the-source-for-music

About the Author

Luke McCready is a technical writer, an audio engineer, and a music lover based out of Boulder, CO. He graduated with a degree in audio engineering from North Central University with a passion for audio and a fascination for speaker setup and acoustic treatment.