In the development process leading to the company's new VR headset, Valve has made significant progress not only in the display, lens, and field of view aspect of VR goggles, but certainly - and the reason why I decided to highlight the story this week - on the aural side.

Detailing the R&D process leading to the design of the Valve Index Headset, Emily Ridgway, audio researcher at Valve Software, describes the company's take on what they call "off-ear headphones" or "ear-speakers." The interesting concept, akin to a lot of research done by companies such as Sennheiser, JBL, and Bose, intends to create a personal audio field that doesn't necessarily rest on the users ears, particularly while enjoying entertainment and interactive experiences (e.g., gaming).

But while those mentioned companies have explored the unsuccessful concept of around-the-neck (collar-like) sound emitting systems (read more about it here), Valve has opted to explore transducers that radiate directly at the ear, suspended on the VR headset structure, but not touching the user's ears (supra-aural). The motivation, as Ridgway details, was to optimize for the "specific experiential goals of virtual reality," leading the team to diverge in interesting ways from that of typical consumer headphones.

Valve's research led the company to explore how VR sound content, as processed by game engines, can reach the ear in different ways. They explored binaural simulations and the effects of head-related transfer function (HRTF) to better convey the position of a sound source and explore the sense of reality in the different frequencies. And even though the team recognizes that traditional headphones "provide more direct spatial sound information," and can excel in areas such as sound isolation, power efficiency, and noise cancelling, they do not contribute effectively to the "audio immersion" effect Valve was looking for with VR content.

Because headphones and earbuds need to make contact or surround the ear in order to achieve their goals optimally, they sound different (inside the head) from the "natural listening process caused by ear and head interacting with real sound waves," the company describes. Also important for the application, headphones can cause ear pressure that gets painful and uncomfortable after periods of time.

As a result of those considerations, Valve decided to explore the supra-aural approach, including testing beam-forming and immersive speaker setups, which were discarded for its field restrictions for accurate spatial playback and on freedom of movement. Instead, the solution they agreed upon explores "a pair of ultra near-field, full-range, off-ear (extra-aural) headphones. Close enough to the ear to mimic player-relative stereo headphones and support the output format of current VR content, but far enough away to allow the ears and head to imprint their own tonal coloration onto the sound, while also addressing comfort and pressure issues."

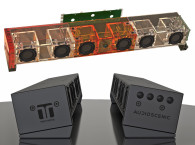

The team developed different prototypes, starting with adding desktop speakers to the outside of a helmet, and testing large-size headphones (including custom planar drivers from Audeze), only to realize that the results always had limited bass response. Any variations in speaker positions caused by putting on the helmet differently or moving around in VR caused the volume, frequency response, and sound balance to shift significantly. And more importantly, the tested contraptions where too heavy and caused huge sound leakage. Valve also explored using actual headphone drivers instead of speaker drivers but found out they couldn't deliver enough volume when held away from the ear in free-air.

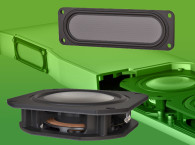

The Valve team finally selected a pair of Balanced Mode Radiator (BMR) drivers from Tectonic, which were found in early tests to reduce coloration due to speaker mispositioning, had lower weight, great frequency response in high-mid ranges (important for binaural simulations), and were much thinner than traditional speaker drivers.

When the final form factor for the Valve Index Headset system was set, a 3D printed prototype of the ear-speaker headphones was created allowing further measurements. For the final off-ear speaker product, Valve worked with Tectonic to design a 37.5 mm custom driver, which is detailed as having a 40 Hz to 24 kHz frequency response and being able to reach 96 dB SPL at 1 cm.

Further field tests with prototypes provided positive feedback on the benefits of not having anything touching the ear. Users reported an increased sense of sound immersion, and no complaints about external sound coming in and/or internal sound leaking out. As Ridgway details, after further measurements on a dummy head, the design was found to have a very low crosstalk, comparable to open-back headphones. The combination of EQ tuning, the use of DSP, and the cooperation with Tectonic, which worked to improve the bass mechanically by optimizing the speaker driver itself, allowed the team to achieve and exceed the desired sound quality and bass response goals.

As Ridgway explains: "By using BMR drivers, we are able to ensure consistent sound quality, without coloration, even if the speakers are slightly mispositioned on the side of the head. This is due to the unique way that BMRs radiate sound. (...) Basically, ensuring that your ears always receive the full sound information - even if they are not perfectly aligned with the BMR speakers."

Additionally, the team was also able to explore the "self-baffling" features of the BMR drivers to mechanically minimize sound leakage with an open back design, preventing sound below 3 kHz from bothering people nearby. "The listener wearing the headset has the ears so close to the drive unit (near-field) that the cancellation is not perceived as the pressure from the front side is RELATIVELY so much closer to the ear than the rear side," adds Tim Whitwell, from Tectonic.

"All this research, iteration and feedback leads us to believe that the Valve Index ear speaker design is as close to an optimal balance of trade-offs and features specifically designed for audio playback in room-scale VR as currently possible. We're really pleased with how the audio experience played out and, that said, there is still much more to learn and more improvements we can make," she concludes.

Now, the question that Valve needs to ask (as well as all the VR companies) is, do we really need to place a blind-fold on people's heads and stick screens in front of our eyes to play a game, just so we have an illusion of a different reality? My take on this interesting development is that this should be experimented with as an audio-only solution for gaming with external displays as well.

www.valvesoftware.com