The following is an overview of the aptX audio codec technology, and my personal journey, now that after 28 years I have decided it was time to move on. However, before diving into the details, I must explain how aptX became interlinked with my professional career.

Having graduated from the University of Ulster at Jordanstown, Belfast, in 1986, I joined Dolby Laboratories in London and worked on the Dolby SR (Spectral Recording) noise reduction format and cinema products. I did two stints with Dolby between 1987 and 1992, which were interspersed with time in Australia and working with Ericsson on analog Cellular Base Stations.

In 1993, before the Peace Agreement in Northern Ireland, I wanted to move back to Ireland. It is a superb country and the outbreak of peace offered hope to the diaspora to return home. Audio Processing Technology (APT), Ltd., headquartered in Belfast, offered me a job in customer support and that started the aptX journey. I moved into sales in 1994 and relocated to the Los Angeles, CA, office, then became the commercial director in 2000, and later in 2005, with Noel McKenna, became a co-owner via a managment buyout (MBO).

Data Compression

The history of digital audio data compression goes back to the mid-1980s. At that time, digital was taking over from more traditional analog storage, playout, and transport mechanisms and once digital music became available, there was an obvious need to reduce storage space and data rates due to cost and space implications. Back then, only a handful of technical pioneers were capable of developing audio compression algorithms, namely James D. Johnston (Bell Labs, AT&T, and Microsoft) and Stephen Smyth along with places, such as the Fraunhofer Institute in Germany and Sony Corp. in Japan. Also making a significant impact were Peter Craven and Malcolm Law of Algol Applications, Ltd. Essentially, all original and innovative thinking on audio compression/decompression (codec) techniques date back to these names.

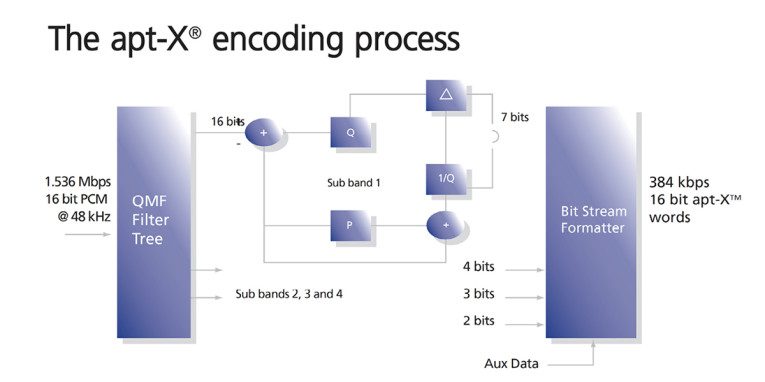

Codec architecture had three schools of thought: Adaptive Differential Pulse-Code Modulation (ADPCM), perceptual, and fractal/wavelet-based. There are five key metrics for a codec, namely compression ratio equating to bit rate or storage space, audio quality, latency, power (MIPs/Memory) and robustness (although this can be addressed via additional forward error correction - FEC - techniques). Most commercially successful codecs will generally have addressed at least three of these demands. The original aptX Codec, which used ADPCM, addressed latency, audio quality, and robustness. Although a little heavy on MIPs, it was light on memory (RAM) requirements.

There was also an over-dependency on data rates, which can be seen as a tradeoff for latency and real-time applications. Conversely, MP2 (MPEG-1 Audio Layer II using Perceptual coding techniques), which was the emerging codec from Fraunhofer at the time (before MP3 or MPEG-1 Audio Layer III), offered exceptional bit rate and MIP efficiencies but fell down on latency and audio quality. However, the value of being able to cram more music into a smaller space had its own attractions, regardless of the consequences. Elsewhere, Sony was forging ahead with ATRAC and Algol with Meridian Lossless, which ultimately became Dolby Lossless/TrueHD.

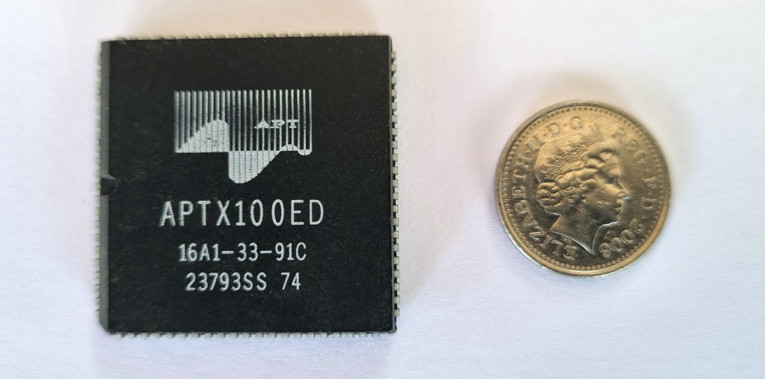

As stated, my own journey started with APT in Belfast in May 1993, almost a full week after Stephen Smyth left to join DTS, where he later developed the Coherent Acoustics algorithm. Stephen, along with his brother Mike and colleague Paul Smith, had already set up APT, Ltd. in 1988 using seed funding from QUBIS (the commercialization arm of Queen’s University, Belfast) and Solid State Logic (SSL). Stephen received his PhD in digital audio data compression, which partially looked at G.722 as a two sub-band, 14-bit voice algorithm and moved that to a 16-bit, four sub-band music codec (aptX100). This investment in APT allowed the founding team to tape out a chip known as the APTX100ED using a masked ROM from AT&T.

Stephen took his team over to California and was at the epicenter of DTS’ march into consumer electronics. The legacy was DTS’ continued use of the APTX100ED chip for its cinema products, due primarily to the low latency of accessing stored content, which ensured synchronization between audio and film. DTS and aptX100ED were given a huge boost when Steven Spielberg decided to use this format for his movies, most notably the Jurassic Park franchise and Saving Private Ryan.

Meanwhile back at APT, in Belfast, a range of products servicing the needs of the radio and voice over/ADR/stereo mix approval industries were being developed. In addition, selling the APTX100ED chips to a range of OEMs in the radio broadcast industry was progressing very well. The chip was also incorporated onto a PC sound card, which was sold to radio automation playout system providers. At the time, the company had around 30 employees, was turning over approximately £3 million per annum, and had just won the Queen’s Award for Export. The legacy of Stephen Smyth and his cohort guided APT for another five years before a lack of innovation started to cause some pressure.

Toward the end of the 1990s, the pressures built further when AT&T/Lucent issued an “end of life” for the APTX100ED chip along with the diminishing cost of storage space as Moore’s Law became apparent. The lack of a viable alternative to a chip combined with a saturated VO/ADR market and the radio automation system moving to Linear PCM, meant that the future was not very bright. Corporate activity with SSL and a consistent lack of ability to produce stable, cost-effective products for the radio industry were also factors in the scaling back of the company. It all came to a head in 2004 when SSL went into receivership. APT was bought out from the receivers in an MBO using VC’s funds from Crescent Capital in Belfast and Trinity Venture Capital in Dublin. We began management buyout negotiations with SSL in January 2005. APT Licensing, Ltd. was incorporated in March 2005.

From Broadcast to Bluetooth

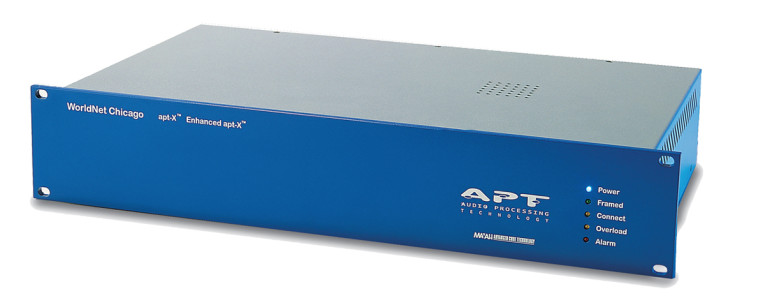

APT was always profitable and, under new management, the three key objectives were to build hardware devices that addressed the needs of the broadcast market, develop licensing, and freshen the roadmap for new audio codecs. Given that the primary usage in the radio industry was for mission critical applications (e.g., studio to transmitter links, station networking and remotes as well as outside broadcasts), a bulletproof, highly redundant range of products that ensured “dead air” never occurred was of the utmost importance.

Getting this correct while at the same time embracing the migration from synchronous to IP networks, allowed APT to get back on the road to recovery. The winning of a tender by the European Broadcasting Union (EBU) for the networking of all EU Public Service Broadcasters for stereo and 5.1 content opened the flood gates and the company was back in the game and making a competitive comeback.

At the same time, the licensing business was being developed but wholly focused on professional applications. Sennheiser (which was familiar with aptX from digital wireless microphone applications) tabled an interesting opportunity from its Consumer Electronic Business Unit. Sennheiser asked APT to look at the emerging Bluetooth market as they believed the incumbent low-complexity subband codec (i.e., SBC) was not fit for the purpose. In 2008, Sennheiser launched its first Bluetooth device at CES and APT won the “Best of Bluetooth” award from the CES Committee.

With approximately 60 employees in 2009, a turnover of £6 million and numerous awards for innovation and growth, the expansion/development of the company was clear to see. APT had been split into two companies—APT Hardware Limited and APT Licensing, Ltd. In 2009, APT Hardware was sold to the French company Audemat (today part of WorldCast Group) and the proceeds were returned back to the initial investors.

APT Licensing, Ltd. went on to win deals with Apple, Motorola, Nokia, and Microsoft and in 2010 Cambridge Silicon Radio (CSR PLC) swooped in to acquire the company. CSR was a pioneer of the integrated Bluetooth and processing platforms. Their approach boosted the roll out of Bluetooth initially for voice and later for music.

In 2015, CSR was then acquired by Qualcomm, which wanted to pursue a strategy of joining up handsets to earbuds to ensure an optimum experience for music, video, and gaming through an integrated approach known as Q2Q (Qualcomm to Qualcomm). This furthered the roadmap of aptX with the launch in 2018 of aptX Adaptive supporting 24-bit/96kHz and along with aptX Voice for super-wideband voice quality to complement VoLTE on 4G and 5G.

aptX Adaptive was designed to be dynamically adjustable, combining the features of low-latency aptX, aptX (Classic), or aptX HD, depending on the content and the connectivity.

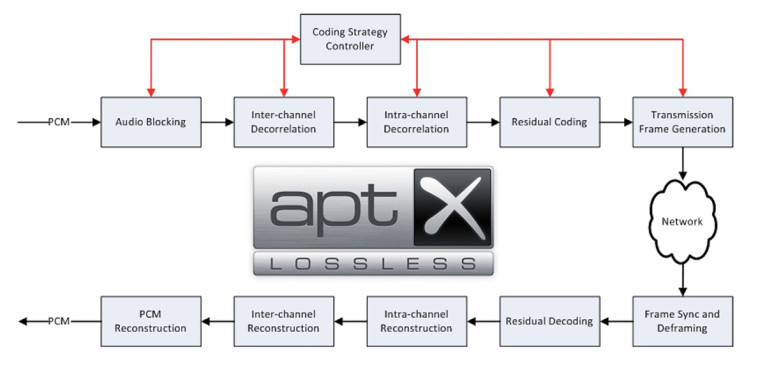

The culmination of this technical journey was the ability to deliver Lossless CD quality via aptX Lossless, which is a function of improved data throughput that’s the result of combining Qualcomm High Speed (QHS) and the scalability of aptX Adaptive. Introduced in 2021, aptX CD Lossless technology delivers bit for bit exactness when compared to the original Linear PCM, expanding the options available for Bluetooth wireless audio, combining codec, wireless link, and RF optimizations. Bluetooth is now fit for the purpose for music.

Nobody at the Table Went Hungry

The end of my professional journey culminated in aptX being subsumed into Snapdragon Sound, which addresses audio quality, latency, and robustness by marrying the aptX Codec with QHS Link modulation. Between aptX and Snapdragon Sound there have been more than 1,000 license agreements signed and aptX is used in more than 12 billion devices across handsets, PCs (both Microsoft and Mac), headsets, earbuds, speakers, soundbars, TVs, cars, and happily LP record players.

There are even metal and water leak detectors using aptX over Bluetooth. Adding in the professional applications for radio and voice over, with digital wireless microphones and a successful entry into the security sector, the story of the aptX brand is writ large.

Having said all that, and for the sake of balance, it is worth noting that there may be headwinds. The Bluetooth SIG works slowly, but there is a strong probability that the Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) solution with LC3 will address low latency use cases and it should be a much better codec than Bluetooth’s classic SBC codec from an audio reproduction perspective.

Fraunhofer will augment the audio experience with LC3+ for higher quality again. If you add in LDAC and LHDC codecs, then this period could be considered the golden era of audio coding in terms of choice. What will need to be addressed, and what Qualcomm is achieving, is the Interop testing to ensure a consistency of experience across the three performance pillars of audio quality, latency, and robustness. This takes time and investment but will be well worth the effort in terms of underwriting brand value.

I hope that my own personal journey in the future will be as interesting, varied, and successful as the past 28 years. Having worked in audio networking for radio before becoming involved in delivery via Bluetooth, the last piece of the jigsaw is content generation and acquisition. Considering the challenge around RF connectivity, simply because of the sheer volume of devices in the 2.4GHz space, there could be value in improving the antenna design, especially given the reduced form factor in earbuds, which will ultimately result in body blocking and range issues. Merging knowledge around codecs and RF could help in digital wireless microphone for news reporting, music, and talent use cases. If you’ve made it to the end of this article, many thanks for persisting. Better still, if the last few lines resonate, please feel to get in contact via my LinkedIn profile. aX

This article was originally published in audioXpress, October 2022

About the Author

About the AuthorJonny McClintock has worked in the audio industry for more than 30 years, the majority of that time he was been involved in the marketing and selling of aptX. He has recently left Qualcomm and is currently the Commercial Director for AntennaWare | Wearable Antenna Technology | Made To Wear and he has a consulting role with Sonical.ai. His passion is driving start-ups.