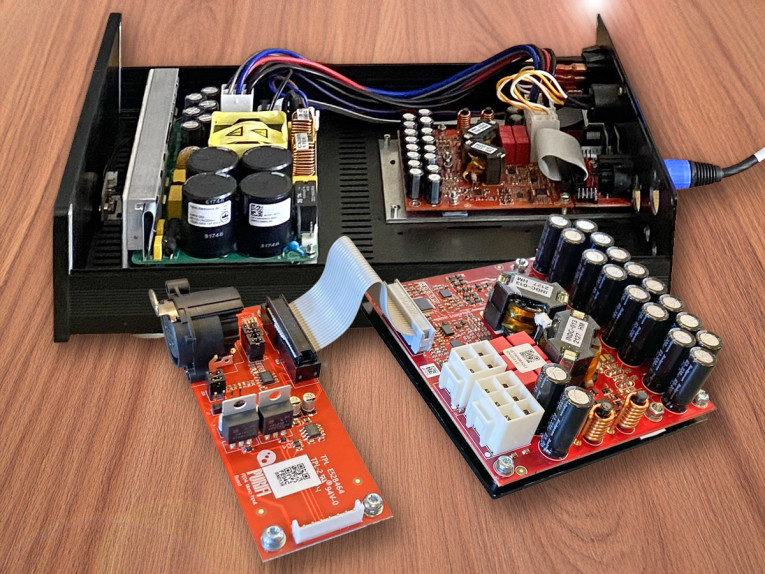

Just prior to commercial availability, Bruno Putzeys, Purifi Audio’s co-founder, co-owner — and CTO and the designer of the Eigentakt amplifier series—kindly loaned us a pair of 1ET9040BA modules mounted in simple black boxes (Photo 1). For this review, Audio Precision’s parent corporation Axiometrix Solutions provided an APx555B analyzer to complement our existing test bench, following Putzeys’ own recommendations. Still, the very high linearity and very low distortion of the Purifi amp made it unexpectedly difficult to measure.

The 1ET9040BA is a balanced, bridge-tied-load (BTL) amplifier, and the second product in the company’s Eigentakt range, following the 1ET400A module, which has been available for some time and was reviewed by audioXpress in July 2020 [1]. The test amplifier set we received consisted of two monoblocs each with their own switched-mode power supply (SMPS) — a high-power Hypex unit. As is often the case with Purifi amplifiers, these are the basic power amplifier section, and most users would precede them by a buffer/gain stage so they can be driven by a low-level audio source.

Purifi has such a product available for those who don’t want to roll their own. The power amplifier itself can be set to different gains with some jumpers. Since the APx555B has enough output voltage, we tested the amplifiers without an input/gain stage. For the measurements, we set the amp to a gain of 14.4dB. Of note is the preferred connection between the amplifier output and the speaker load. Purifi uses a four-wire SpeakOn connector on the amp side, with two pairs connecting the amp to the speaker.

Harmonic Distortion

We were expecting very low distortion values from this amplifier so we started by doing a loopback test on the APx to make sure we could reach the unit’s low distortion limit. That was a small project in itself, and it was only after we used the dedicated AP test kit XLR test cables that we could reach the full potential. These test cables didn’t look any different from our own cables, using the same Neutrik connectors and similar cables (Mogami Neglex 2534) as we did. We had often wondered in the past why the AP cables were relatively expensive — now we know! We did all measurements through an AP AUX-0025 25kHz passive low-pass Class-D measurement filter (top of the stack in Photo 1) to make sure that the auto ranging and tuning circuits were not impacted by any amplifier switching components. The amplifier (Photo 2) without the input buffer stage has a fairly low input impedance. All testing was performed with a balanced source signal with an output impedance of 40Ω.

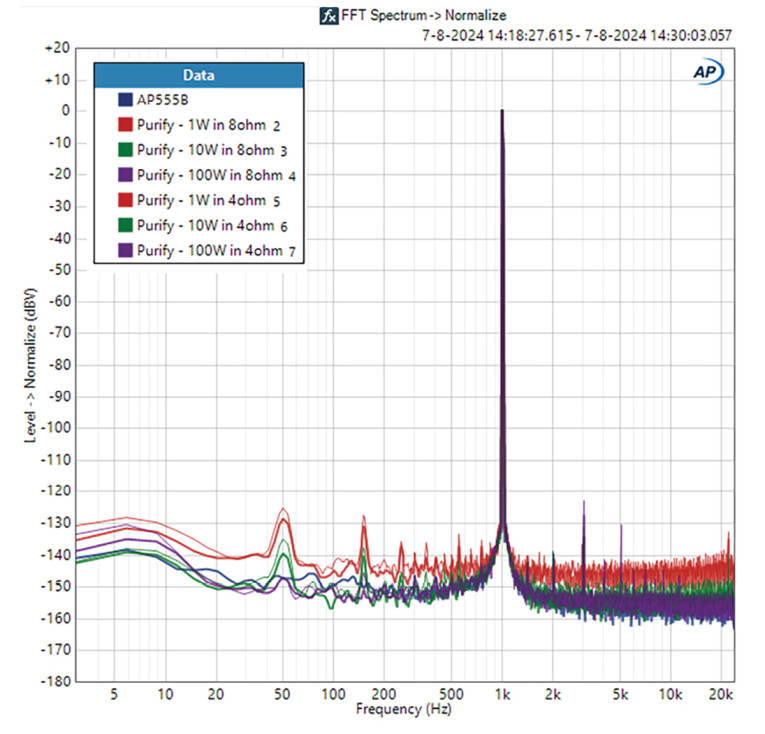

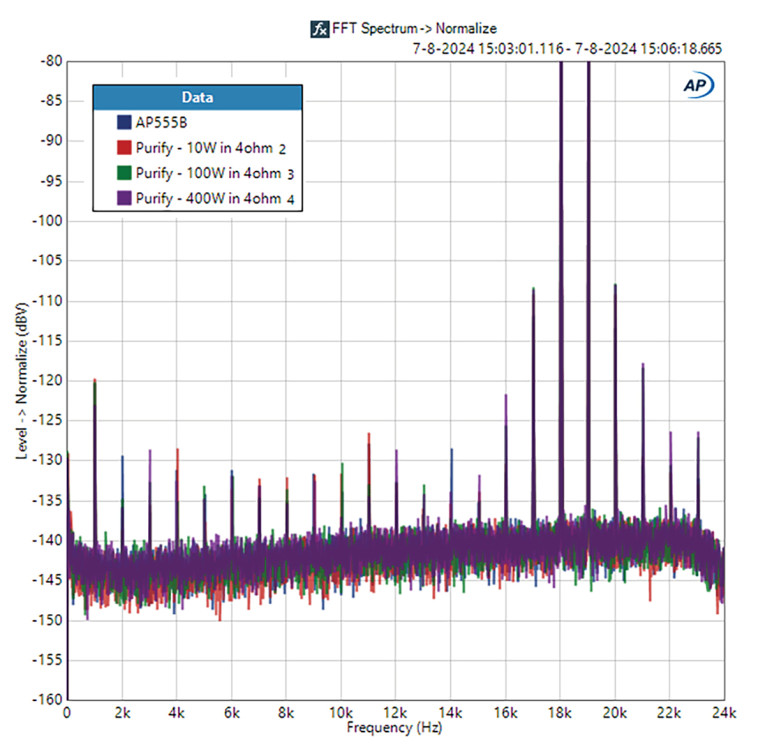

We started with the usual 1kHz FFT to see what the distortion spectrum looks like (Figure 1). We tested at 1W, 10W, and 100W, both in 4Ω and 8Ω loads. That makes the graph in Figure 1 a bit busy, but the conclusion is clear: in all these conditions, harmonic distortion is below 1ppm (-120dB), and in many cases significantly lower than that. Impressive.

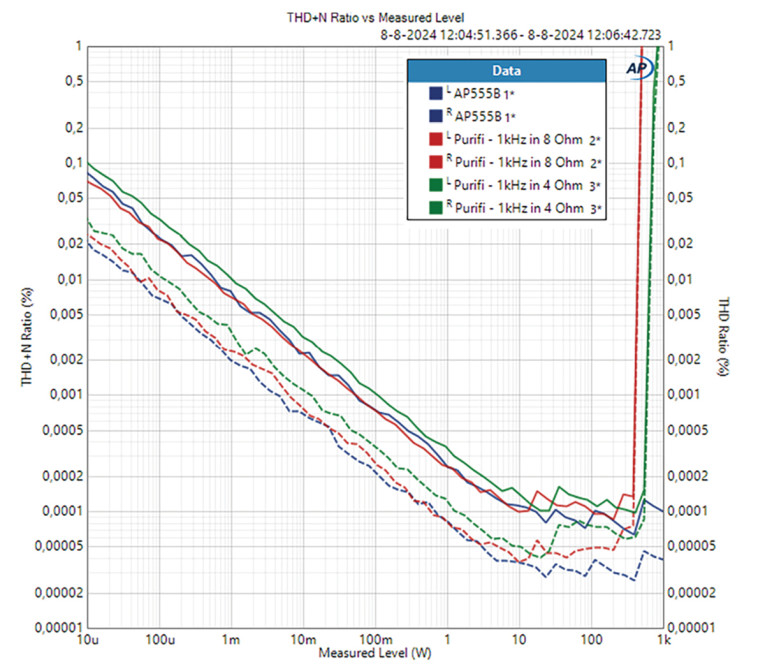

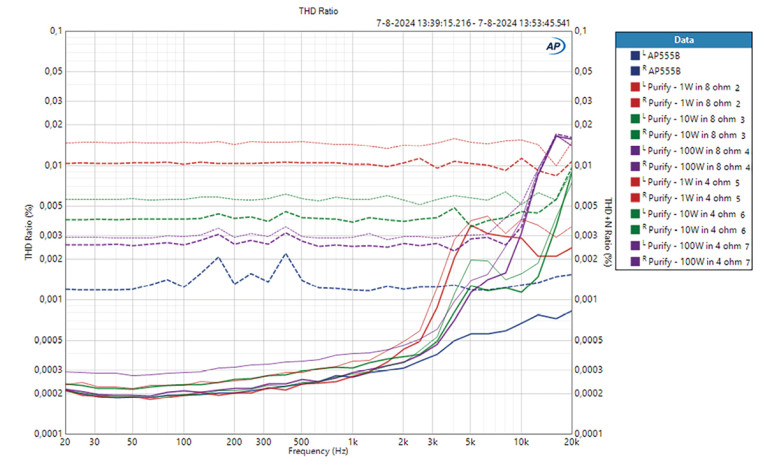

Figure 2 shows the distortion versus power. That is one of the graphs where we needed the AP test cables to reach as low as is shown. The amplifier distortion basically follows the APx555B residual distortion lines, and only above 10W or so does it climb above that. A boring graph: that amplifier adds nothing or very little to what the APx does. Distortion versus frequency (Figure 3) is very similar. Only above 2kHz or so does it show anything above the APx555B residual. In this graph, the right axis shows the THD+N ratio and the noise level of the amplifier is higher than that of the APx.

Intermodulation

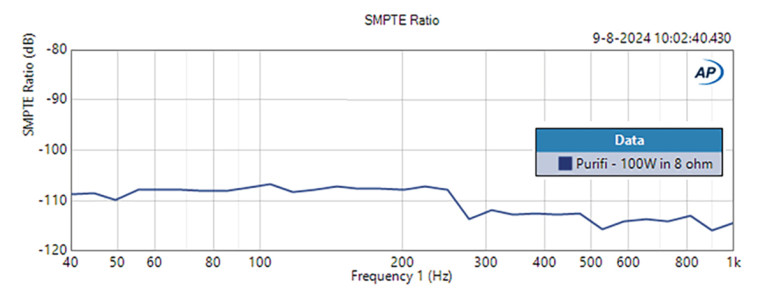

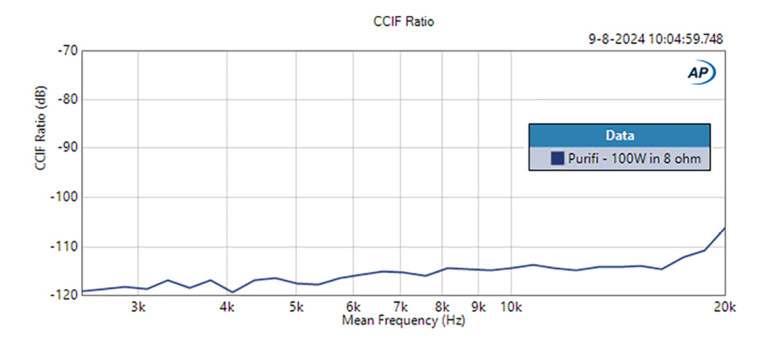

Next, we did some intermodulation tests. The rationale for such tests is that they give a better view of how the amplifier would perform when fed with multiple frequency signals, which are more music like than a single frequency sine wave. It should be noted however that both a total harmonic distortion (THD) and an intermodulation distortion (IMD) test exercises the same nonlinearity in the amplifier, so wildly different results should not be expected in a competently designed amplifier. For comparison, we did all three usual IMD tests: SMPTE, CCIF, and Multitone.

Figure 4 shows the result for the customary 18kHz + 19kHz intermodulation test. We deliberately set the Y-axis to a maximum value of -80dBV to be able to zoom in on the low-level intermodulation products. The test was done with 10W, 100W, and 400W all into 4Ω load. The 1kHz difference frequency is at about -108dBV at the highest power level. In most cases, the intermodulation spurs are below -120dBV. But the APx can also show IMD over frequency by keeping one of the frequencies constant and sweeping the other one. That gives us Figure 5 and Figure 6. In Figure 5, the fixed frequency signal is held at 7kHz while the other is swept from 1kHz to 40Hz. In Figure 6, two signals are swept from 2.5kHz to 20kHz, with a difference frequency of 80Hz. Exemplary performance again.

Multitone

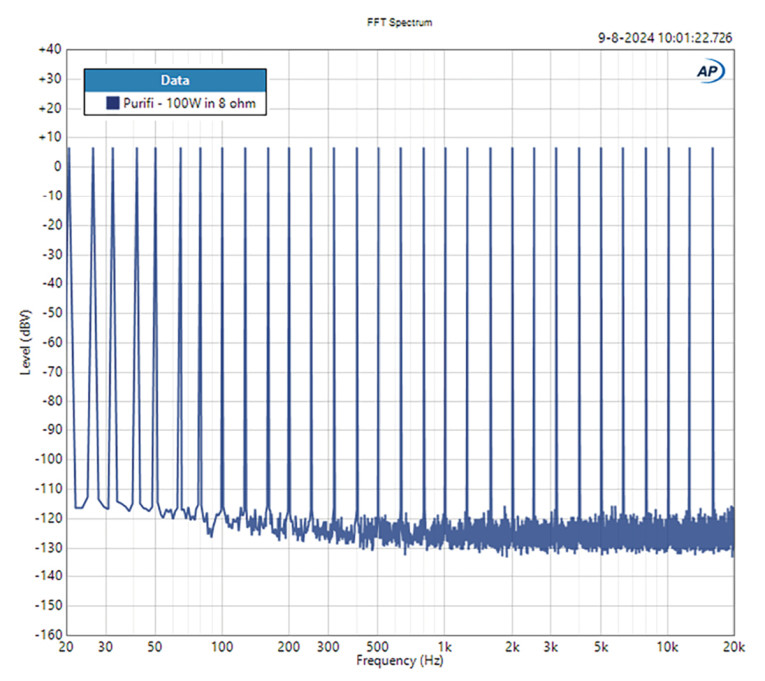

A third way to look at intermodulation with a complex signal is by using a Multitone stimulus. AP has pioneered this test method from the early days, and there is now an IEC Multitone Test defined with an excitation signal containing 31 frequencies over the audio band. The levels of the components of the signal are chosen such that the maximum RMS signal level is not exceeded, and the frequencies are chosen in relation to the FFT parameters so that all harmonic components fall in an FFT bin and can be individually measured and displayed. Throwing such a signal at the Purifi module gives us Figure 7, again showing the distortion and noise components at the -120dB level over most of the audio band.

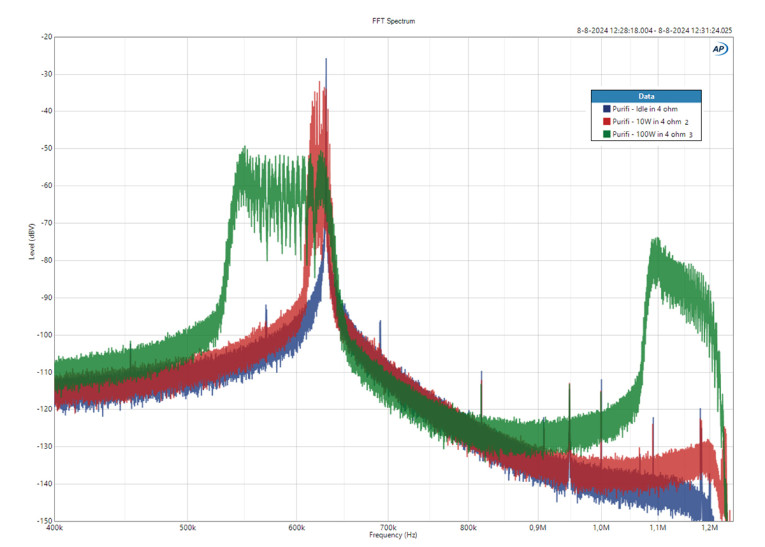

Switching Frequency

Class-D amplifiers always generate frequency components far above the audio spectrum due to their switching nature. In a balanced amplifier like this one this spectrum is common mode and will not impact the audio reproduction. But it can confuse the test equipment and that is why we used a dedicated measurement filter as mentioned at the beginning of the article. Nevertheless, we wanted to get a feel of how that spectrum looked and we show it in Figure 8. The idle switching frequency is just a tad above 600kHz.

You can also see that when the load increases, the switching frequency gets more wideband, spread out down to about 550kHz. These figures are of technical interest but have no bearing on the audio reproduction.

Conclusion

The ET9040BA measured here proves that the old adage “it is either powerful or it is good” is no longer valid. Gobs of power combined with the absolute top in linear performance is here. The performance of this amplifier challenges the best test equipment out there, and all that with dependable and cool-running operation. At a ridiculously low price.

Can it be improved? Yes, technically it always can; for example, distortion still rises with frequency, and we’d rather have that flat. But the performance is beyond the previous state of the art and sets new standards. Well done, Purifi! aX

Afterthoughts

By Jan Didden

So, looking back on the results of the Purifi 1ET9040BA module, what does it tell us? In an earlier review of the single-ended version of this amplifier [1], audioXpress’ regular contributor Stuart Yaniger commented: “Audio power amplifiers are done. Let’s move on.” Putting this amplifier through its paces left us with similar thoughts. Not that I have any doubts that inventive designers will continue to come up with technically even better performing amplifiers. Personally, I doubt that we will be able to hear any audible improvement between an ET9040BA and the next iteration, whether from Purifi or one of its competitors.

I recently got into an exchange on diyaudio.com with a very talented designer who designed yet another Class-AB amplifier. The design had some very clever circuit details to minimize the usual problems with crossover distortion and Gm doubling. I have no doubt that this amplifier will sound clean and transparent, on a par with the very best out there. Its designer commented that his amp would be a “Class-D killer,” and that is where we disagreed. My very first Class-D amp was a Sony TA-N88 from the mid-1970s. It didn’t test very well, and it didn’t sound very well. Many issues with designs like that were not well understood at the time. So, folklore developed saying that Class-D has no place in high-end audio reproduction. The problem with folklore being, of course, that it persists long after the underlying reasons have disappeared. But high-end audio manufacturers today embrace Class-D more and more in their top products. I remember, many years ago, becoming aware that a pair of $80,000 Jeff Rowland high-end monoblocs were powered by Ncore Class-D modules. And the trend will continue. Class-D has already cornered the professional performance and installation markets, and no doubt the technology will be embraced even more in high-end audio products and particularly with the trend toward active speakers.

For a century, audio amplifier designers have improved on the basic linear amplifier concept. By going to better devices, from tubes to germanium transistors to silicon, silicon-carbide and what have you; by inventing better and better linear circuit topologies. Class-D is an improvement in concept. And contemporary Class-D is such a step up in performance that many listeners come up with terms such as “clinical” and “lifeless.” They are so used to amplifiers that add “warmth,” artifacts, and harmonics, often subtle, that they think something is missing. But life, warmth, envelopment, and the like is what music brings with it, not what a transparent amplifier does. Linear Class A and AB amplifiers will go the way, not of the dodo, but of tube amplifiers. You’ll still be able to buy them, and they will even sound good, but they will become a niche, if they are not already.

References

[1] S. Yaniger, “A Tale of Two Class-D Amplifiers Orchard Audio Starkrimson and Purifi Audio Eigentakt EVAL1,” audioXpress, July 2020,

[2] J. Martins, “Purifi Audio: A Conversation About Amplifiers and Speakers,”

This article was originally published in audioXpress, January 2025