However, little attention had been given to halls for jazz performance, partially because jazz was often thought of as dance music, and partially because good acoustics for jazz performances differed little from good acoustics for most types of “serious” music. One exception was the percussive Latin American forms of jazz, which required better clarity and definition in a listening venue.

Rock and pop music began developing a significant concert presence in the 1960s and 1970s, first outdoors, then later in sports arenas and coliseums. The electronic/electroacoustic amplification of rock and pop music added new dimensions to concert acoustics, but for years, these dimensions were ignored, especially in the “sports” venues often used for rock and pop performances, at least in the US.

If an architect or acoustician wanted to design a truly good performance venue for rock and pop concerts, (s)he would have been severely hampered by lack of rigorously determined objectives for early decay time (EDT), reverberation time (RT) in the various octave bands, clarity, definition, intimacy, lateral reflections (LF), room gain (G), bass ratio, warmth, and stage support/ensemble.

Basing a design upon the preferred values of these parameters for other music genres certainly would — and did — result in sub-optimum rock and pop concert experiences. Filling this void in our knowledge of audiences’ acoustical preferences for rock and pop music venues has been the focus of Adelman-Larsen’s work for more than a decade, and hence, is the focus of this book.

Book Overview

This book was first published in 2014. This review covers the second edition, published in 2021, which is available in e-book, softcover, and hard-cover. The Table of Contents of the second edition differs from that of the first edition mainly in the elimination of the “Endorsements” from second edition. Some changes in wording can be found within the chapter text, but the organization and coverage remain as excellent as in the first edition.

In his introduction, the author succinctly summarizes the challenge that his research addressed: “Pop and rock concerts are unique in that they depend heavily on amplification of the sound that the band produces. A significant ingredient in the music is often a highly amplified and well-articulated bass line supported by a more or less syncopated staccato bass drum rhythm. The precise timing of both, down to few hundredths of a second, is what professional orchestras depend on in order to make hard grooving music not only satisfactory to the orchestra itself but also, most notably, to the audience.

Many other instruments are active in the bass frequency domain. The room’s acoustics should enable this message to be transmitted to the audience with a high degree of intelligibility.

It is evident that if a hall allows the bass tones to last for a long time, then this rhythmic backbone of the type of music we are describing is easily lost. The starting and stopping of bass sounds is converted rather into a long, dull, legato continuum that can hardly be identified as “rhythmic” by performers or audience.

What was expected to be a musical experience is transformed into sound with little sense, sometimes close to noise.” [1] The book begins with an introduction to acoustics and hearing. Readers who have learned about acoustics primarily from high-school or undergraduate college courses in general science or physics will gain new insights as Adelman-Larsen addresses the production, characteristics, and radiation of human vocal sound; the human voice usually contributes the most important components to rock and pop music.

Another particularly valuable part of the first chapter is the discussion of absorption by porous, diaphragmatic (membrane), or resonant elements, and by air. Many of my architect clients could benefit from a study of this discussion, as could many people who design their own home studios.

The Mathematics

The concept of critical distance (the distance from the sound source at which the direct and reverberant sound levels are equal) is well known to most sound engineers and acousticians. But musicians, facilities managers, and others reading this book may not be familiar with it.

Yet understanding the parameters that determine critical distance, and its importance in the listener experience in a hall, is of great importance in understanding concert hall acoustics. The author presents this information using enough math to elucidate the concepts, but not so much as to threaten “math-o-phobes.”

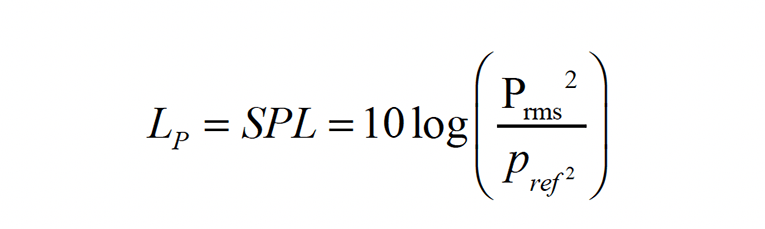

Speaking of math, I should mention a potential source of confusion on page 23 of Chapter 1. The author correctly gives the equation:

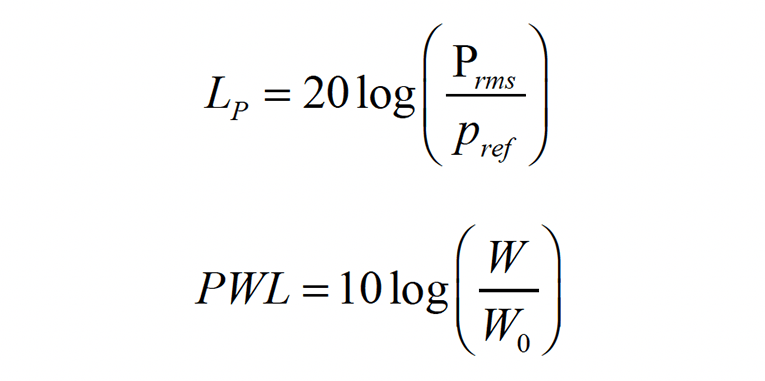

where prms is the effective sound pressure in pascals, and Pref is the reference sound pressure of 20μPa. However, many, if not most acoustics texts give these two equations:

Actually, these equations are equivalent, as you can understand if you know that sound power is proportional to sound pressure squared, which you can infer from the fact that the fraction in the upper equation is squared. Thus, if you double the sound pressure (twice as many pascals: an increase of 3dB) in the upper equation, you’re taking the log of a value four times as large (an increase of 6dB). Often we say that doubling the sound pressure is an increase of 6dB, but doubling the sound power is an increase of 3dB. Without this clarification, the author’s use of “10 log” instead of “20 log” for SPL could confuse casual readers.

Concepts and Terminology

In Chapter 2, the author discusses the concepts and terminology of auditorium acoustics. In addition to RT, he mentions the important but less commonly known parameters of EDT, reverberance, liveliness, clarity definition, early reflections, intimacy, lateral fraction, envelopment, G (strength or room gain), bass ratio, warmth, and ensemble. These are presented clearly and in appropriate detail.

Next comes a presentation of loudspeaker types and their applications to the reinforcement of the music of rock bands. The chapter begins with a characterization of the typical rock-music audio signal. In particular, the author discusses both the levels and the articulation of the bass. In doing so, he lays the groundwork for recommendations presented in later chapters, calling for a different design approach regarding bass ratios.

Leo Beranek defined bass ratio as: BR = (RT125 + RT250)/R(T500 +R T1k)

He considered bass ratio to be the objective parameter corresponding to subjective “warmth.”

Adelman-Larsen redefines the bass ratio: BR = (RT63 + RT125)/(RT500 + RT1k+RT2k)

He finds that this definition corresponds well with subjectively optimum RT for rock/pop venues in the lower versus middle octave bands. In this understanding, BR is more closely associated with “bass intelligibility.”

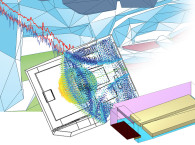

Chapter 3 discusses factors affecting the design of speaker systems for amplified music halls. The author describes the operation and performance of single-point-sources, virtual point sources (clusters, “exploded clusters,” etc.), directional subwoofer arrays, and line arrays. Notably, the treatment of split mono vs. stereo discusses performance issues not always appreciated by system designers.

This chapter will be helpful to musicians, sound technicians, architects, and facilities managers. In 2005, the author made objective measurements and collected subjective data on 20 halls used for rock and pop music. For each of these halls, a photo, a scaled plan drawing, and the data are presented in Chapter 4. In Chapter 5, the author develops recommendations based upon the objective and subjective data.

The February 2023 issue of audioXpress mentioned journal articles in which Adelman-Larsen recommended a substantial decrease in RT in the 63Hz and (most importantly) the 125Hz octave bands for rock/pop halls as compared to more traditional concert halls. On pages 117 and 118, the author summarizes:

Some textbooks on room acoustics recommend that “halls for music” have an increase of reverberation time at frequencies below 250 Hz (despite the fact that many of the very best rated halls for symphonic music don’t show this trait without an audience). Surely, this brings “warmth” to the sound. But this is true only for (unamplified) classical music. For amplified pop/rock music, as shown in this chapter, it is enemy number one!

...

Some consultants have chosen almost anechoic acoustics for amplified music halls, assuming that the only focus point was freeing the audience from undefined reverberant sound. And that hypothesis has in some cases been taken to the extreme, sometimes even without enough focus on absorbing low frequencies. But as shown later, this is not a correct path to pursue. In this chapter, we will see what values of reverberation time are recommended for a given hall volume; it must be relatively short, but not too short, and within limits it can vary with frequency.

The author goes on to discuss his method of investigation and how the results informed his recommendations, which specify optimal RT versus frequency (in octave bands) for halls having cubic volumes ranging from 500m3 to 10,000m3. As indicated earlier in this review, such scientifically-derived recommendations were unavailable in the acoustical literature prior to Adelman-Larsen’s journal articles. [2,3].

Conclusion

The recommendations are augmented by a comprehensive chapter of design principles, making them easier for an acoustician or architect to use. These design principles include a wide range of architectural factors, not only — or even primarily — acoustical parameters. The designer who adheres to these principles will be well on the way to achieving a good music hall design. An extensive gallery of halls used as rock and pop venues, plus four appendices, rounds out this 480-page tome.

I highly recommend Adelman-Larsen’s book to anyone involved in the design of halls used as rock or pop music venues, as well as the musicians and sound technicians who work in these venues. aX

Rock and Pop Venues:

Acoustic and Architectural Design, Edition 2

By Niels Werner Adelman-Larsen

Cham, Switzerland; Springer, 2021

ISBN: 978-3-030-62320-3

References

[1] N. W. Adelman-Larsen, Rock and Pop Venues: Acoustic and Architectural Design, Edition 2, Cham, Switzerland, Springer, 2021, p. viii.

[2] N. Adelson, E. Thompson, and A. Gade, “Suitable Reverberation Times for Rock and Pop Music,” Journal of the Acoustic Society of America (JASA), 127(1) January 2010.

[3] N. Adelson, C-H Cheong, and B. Stofringsdol, “Investigation of Acceptable Reverberation Time at Various Frequency Bands in Halls that Present Amplified Music,” Applied Acoustics, 129 (2018) pp. 104-107.