Sumiko is a company well-known to audiophiles. It’s been a leading manufacturer and importer of high-end audio equipment for more than 40 years. Back in the 1980s, Sumiko imported an excellent line of Grace tonearms, notably the 707 and the 747 models that were praised by the audiophile press. I owned a 747 in the early 1980s and found it to be a very fine arm when used with low-tracking force, high-compliance cartridges. The company has also manufactured phono cartridges, including several incarnations of the Blue Point moving-coil designs that are available in both high- and low-output versions.

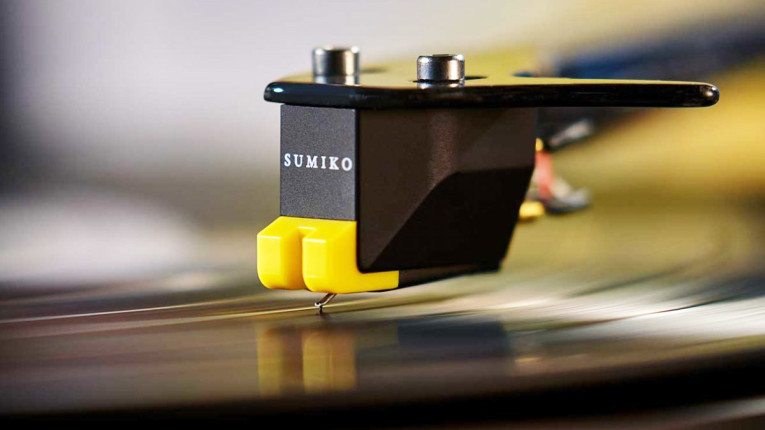

Sumiko also has a line of eight moving-magnet cartridges, all part of its Oyster series. The Oyster series goes back to the first Sumiko phono cartridges, introduced some 40 years ago. It still offers an entry-level Oyster model, a classic design that sells for $79 US. The models reviewed here (Photo 1) are part of a group of four recent designs that feature interchangeable styli. The four cartridges range in price from $79 to $449 US, and also include the Rainier ($149) and Moonstone ($299). Sumiko is now a division of the McIntosh Group.

Traditionally, audiophiles and the high-end press have favored moving-coil cartridge designs over their moving-magnet counterparts. Moving-coil designs generally have much lower internal impedance than moving-magnet types, which results in treble extension an octave or more above 20kHz. The higher moving mass of the stylus and coils often puts the high-frequency resonance point in the upper audible octave, which gives moving coils the sense of “air” that many audiophiles favor, and their low internal impedance makes them immune to the effects of capacitive loading.

In past decades, many reviewers in high-end publications took a negative view toward moving-magnet cartridges, but in recent years that has changed. The resurgence of interest in vinyl has brought with it a renewed interest in moving-magnet cartridges. Moving coil designs still flourish in vinyl circles, but newer moving-magnet designs have earned a renewed respect in the vinyl community.

The cartridge housings (bodies) of the Rainier, Moonstone, Olympia, and Wellfleet models are identical, so upgrades to the next level can be made simply by replacing the stylus. Sumiko notes that the housing has been designed to disperse and dissipate resonances, “making way for effortless, transparent sonics that are enlivened with intimate nuance.” Listeners are said to “experience a diminutive backdrop that bolsters sonic images with a degree of aptitude reminiscent of moving coil designs.”

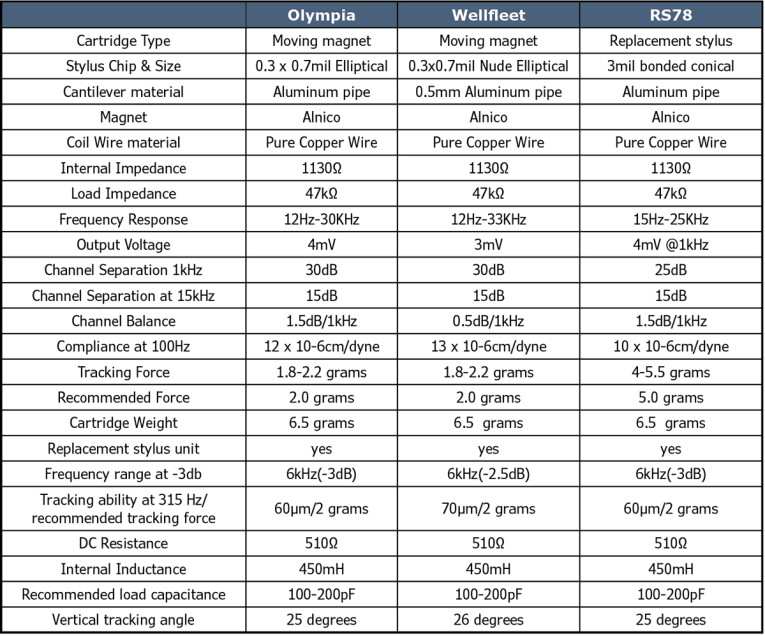

Specifications for the Olympia and Wellfleet phono cartridges, as well as the RS78 stylus, are shown in Table 1. The table gives 6kHz as the -3dB point for the Olympia and RS78; and -2.5 dB for the Wellfleet, which have to be typos. As of this writing, I’ve not been able to get clarification from Sumiko on this specification. I requested frequency response graphs for both models; strangely, Sumiko was unable to supply them. Both models have an elliptical stylus, 0.3 × 0.7 mils.

The main difference between the two models is in the cantilever and the bonding of the stylus. The Olympia has a cylindrical aluminum cantilever with a conventional bonded stylus. With conventional mounting, the diamond tip is bonded to a short metal shank which, in turn, is bonded to the aluminum cantilever. The more expensive Wellfleet has a nude diamond stylus, which means the diamond is bonded directly to the cantilever, without any intervening material. The result is lower mass and improved tracking. This type of mounting is considerably more expensive to manufacture than the type used in the Olympia mounting. The Wellfleet cantilever is a special aluminum pipe designed for improved resonance control. Sumiko claims “a faster, more direct, and more accurate response of the stylus’s movement by the cantilever and magnet. Sonically, this increases speed and focuses central images, pulling them toward the listener with a heightened sense for detail…

Listeners will hear an improvement in surface noise and sense a more distanced backdrop, facilitating a deeply suspended image.” Sumiko also makes an Amethyst model which sells for $599, and looks similar to the other four models. But, the Amethyst stylus is not interchangeable with the others. The cartridge body has a much lower internal impedance and the stylus is a nude, line-contact type. Note that while line-contact styli can deliver superior performance to conventional elliptical styli, they are more sensitive to vertical tracking angle (VTA). Individual VTA adjustment may be required for different records.

The Sumiko models reflect two trends in phono cartridge design that have emerged during the LP revival. First, they’re less sensitive to capacitive loading than their predecessors. It was fairly common in past decades for moving-magnet cartridge manufacturers to give a specific recommendation for the capacitive load, usually between 100pF and 300pF. These days, most moving-magnet cartridges will operate within a fairly wide range of capacitive loads.

The Sumiko models will perform to specification anywhere between 100pF and 200pF, which should accommodate most high-performance tonearm cables and preamp inputs. Second, the recommended tracking forces are higher than cartridges from the 1970s and 1980s. Back then, many moving-magnet cartridge manufacturers placed an emphasis on excellent tracking at very low tracking forces, with typical manufacturer recommendations in the range of 1 gram to 1.5 grams. The legendary Shure V15 series led the pack in this area. But, many audiophiles and high-end reviewers found that ultra-low tracking forces came with a price — two-dimensional soundstage reproduction, flat dynamics, and a lack of high-frequency extension and air.

These days, one look at the specifications for most moving-magnet cartridges shows that priorities have shifted. Tracking forces for most audiophile-quality moving-magnet cartridges are typically in the range of 1.5 grams to 2.5 grams, comparable to many moving-coil designs. All four Sumiko models with interchangeable styli are rated from 1.8 grams to 2.2 grams, with 2.0 being optimum. The trade off has paid dividends, resulting in greater acceptance of moving-magnet designs in the audiophile community. Today’s moving-magnet designs generally have soundstage reproduction, dynamics, detail, and high-frequency extension that are much improved over their predecessors. They also work well in many of the same medium-mass tonearms compatible with moving-coil designs. The general view in the audio industry is that tracking forces around 2 grams do not cause excessive record wear.

78 rpm Stylus

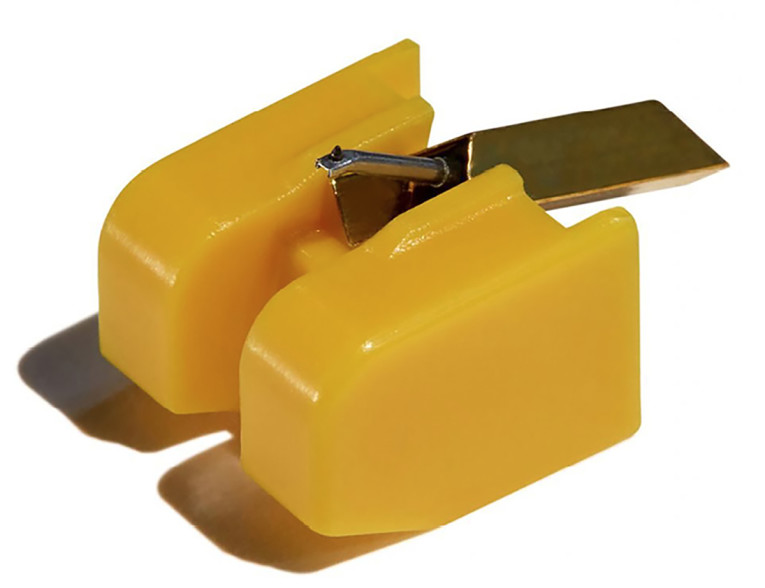

The most recent addition to the Sumiko line of replacement styli is the RS78, a stylus made especially for 78 rpm records (Photo 2). The RS78 features a bonded, spherical (conical) 3.0 mil diamond stylus and a cylindrical aluminum cantilever. Normally, 78 rpm records require higher tracking forces than vinyl LPs, and the RS78 is rated from 4.0 grams to 5.5 grams, with 5.0 grams recommended. The RS78 fits all four models in this line, and the stylus is available only as a separate purchase. You’ll need to buy one of the four cartridges with an LP stylus in order to use it.

The description of the RS78 on the Sumiko website has a one statement that might confuse the reader. In the first paragraph the company notes that the RS78 has a spherical diamond stylus. But, in the next section it states that it’s “not advisable to play 78rpm records with a diamond stylus.” What they mean is “diamond LP stylus,” and Sumiko later clarifies matters by correctly stating that the microgroove styli made for 33-1/3 and 45 rpm records will sound poor and can cause damage to 78 rpm records. Sumiko notes that since the four Oyster cartridges meant to be used with the RS78 are stereo, the RS78 will still yield a two-channel output. But, since 78s are mono, the same information will be heard in both channels.

Mono vs. Stereo Cartridges

There’s a school of thought that monaural records sound best played with a monaural cartridge. Some cartridge manufacturers are making mono cartridges specifically for playing mono LPs. In a perfect world, I might agree with this. But, the two groove walls of a monaural record are often not absolutely identical. This is as true for 78s as it is for mono LPs. There are mechanical limitations in the cutting and the pressing process that often prevent the groove walls from being absolutely identical, and wear patterns on older records are often dissimilar in the two groove walls.

Beginning in the early 1970s, many monaural records were being mastered on stereo cutters. This virtually ensures that the two groove walls won’t be identical. Most preamps made for archival use have a mono mix control — sometimes called a canting control—that allows the optimum mix of the two groove walls. Most audio transfer and restoration engineers prefer to do a stereo transfer to digital, followed by digital azimuth correction and mono sum. In short, I agree with Sumiko’s decision to make the RS78 function as a stereo pickup.

My main musical interest has been classical since I began collecting recordings in junior high school. Although I am an audiophile with a serious interest in high-end reproduction of stereophonic recordings, much of my collecting and listening has always been focused on historical, pre-LP material, the era in which many of my favorite artists performed and recorded. I’ve been playing 78s, and building better mouse traps to get the most from them, since I was a kid. Like most 78 collectors, for many years I used a one-size-fits-all 78 rpm stylus, usually conical types with sizes in the 2.7 mil to 3.0 mil range.

Around 1980, as I become more serious about getting the most out of my vintage records, I began using truncated conical and elliptical styli in various sizes sold by Owl Audio Products, custom made for them Stanton Magnetics for their 500AL cartridge. Owl is long out of business, but at one time it stocked more than a dozen truncated styli in various sizes ranging from 2.0 mil to 6.0 mil, to accommodate vintage commercial records dating from the turn of the last century through the end of the 78 era in the early 1950s, as well as broadcast transcriptions and various “instantaneous” recordings.

Many more stylus sizes were available on special order. Truncated styli aren’t rounded on the bottom like conventional styli. Instead, they’re squared off at the bottom, with rounded and polished corners. The truncation prevents the stylus from dragging the bottom of the record groove, which always increases noise. They allow precise matching of the playback stylus to the groove size. Record groove sizes varied during the 78 era. The earliest 78s have a much wider groove than those made in the 1940s. I often use styli in the 3.3 mil to 3.8 mil range for records made before 1920, yet post World War II discs often play best with a 2.5 mil stylus. Having a variety of truncated styli also allows you to pick a size that plays above or below the wear area, if the record is worn. Since the demise of Owl, high-quality truncated styli have been increasingly difficult to find.

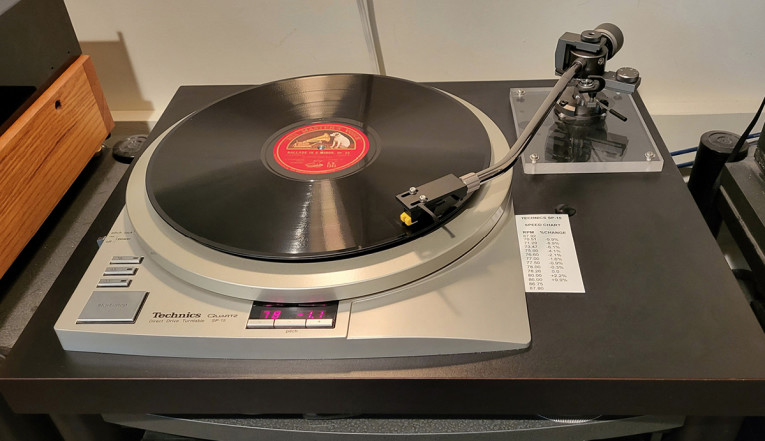

For many collectors, there’s still a need for a high-quality, one-size-for-all 78 rpm stylus, with 3.0 mil usually providing a good compromise that will accommodate most records. Sumiko initially sent me an Olympia LP cartridge, so I evaluated the RS78 stylus in that cartridge body. I used my archival turntable for the evaluations, a Technics SP-15 on a custom base fitted with a Jelco SA-750L tonearm (Photo 3).

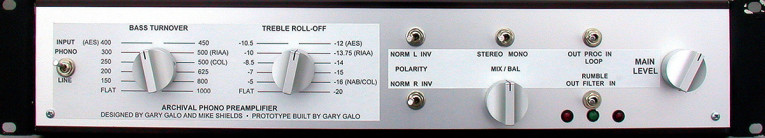

The preamp I used for archival work is my own custom-built Archival Phono Preamp (Photo 4), jointly designed by myself and D. Michael Shields, an engineer based in Minneapolis, MN. I described this preamp in an article I wrote for Linear Audio back in 2012 [1]. The preamp has separate bass and treble phono equalization adjustments to accommodate the myriad equalization curves found on records made before the RIAA curve became the industry standard. There are 12 bass turnover and 12 treble roll-off settings, including flat positions for playing acoustical recordings. Polarity can be inverted in either channel, which is required to switch between laterally- and vertically-cut records. A mix/balance control allows adjusting the mix of the two groove walls, and the preamp also includes a 30Hz, 18dB/octave rumble filter and an external processor loop.

Records for Evaluation

I put the RS78 stylus through its paces on a variety of 78 rpm records, and I’ve included a selective list in this review. I’ve indicated the exact speeds used for each record. This is because, prior to the 1930s, “78 rpm” was just a ballpark figure. Before electric motors became standardized in disc recording and playback equipment, record speeds varied, often considerably, from the nominal value of 78 rpm. A variable-speed turntable is essential for the serious 78 collector in order to correctly reproduce the exact pitch at which the original performance was done. Prior to 1925, all records were acoustically recorded. It was a purely mechanical process in which the performers projected into a large horn which collected the sound, feeding it to a vibrating diaphragm that cut the record groove.

Western Electric began its development of electrical recording several years before the system was finally deemed ready for commercial use. It was a natural extension of their ongoing research on telephone transmission [2]. A microphone turned the sound vibrations into alternating current which, in turn, was amplified by a vacuum tube and fed to a magnetic cutter head. By 1925, the system had improved enough to be marketed commercially, and by the following year nearly all record companies had converted to the electrical process. I have noted which process was used for each of the recordings I list.

The vast majority of acoustical disc records were laterally cut but a few labels, notably Edison and Pathé, made vertically-cut discs (both companies also made cylinders, which were always vertically cut). In order to play both types of records with modern electrical equipment, a stereo cartridge is essential. For laterally cut records, the left and right channels are summed to mono “in phase” (same polarity, to be technically correct). This sums the lateral musical information and cancels the vertical component, which is primarily noise. For vertically cut records, one channel must be inverted in polarity before summing to mono. This sums the vertical musical information and cancels the lateral component which, again, is mostly noise. Note that vertically-cut records can’t be played with a conventional monaural cartridge, and dedicated vertical cartridges haven’t been available in decades.

RS78 Performance

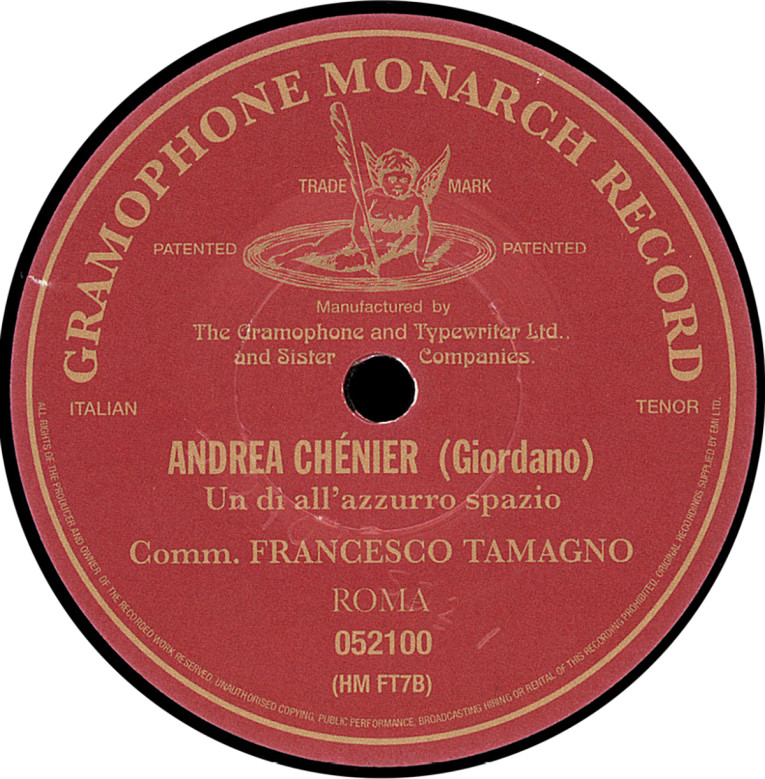

Label scans for a few of the records I used for evaluating the RS78 are shown in Photos 5–8. I found the RS78 to be an excellent all-purpose stylus for 78 rpm records. There’s a school of thought that because 78 rpm records pre-date the high-fidelity era, any magnetic cartridge with an appropriate stylus will be sufficient. Serious collectors and restoration engineers know better! There’s far more information in those vintage record grooves than the original playback equipment could possibly extract. Over the many decades I’ve been playing 78s, I’ve experienced better sound from those records with every improvement in playback equipment, whether the cartridge and styli, the tonearm, the turntable itself, or the preamp.

The Sumiko cartridge fitted with the RS78 stylus shows the benefits of using an audiophile-quality cartridge with 78s. The RS78 offers a level of detail and definition across the frequency range of these records that lesser 78 cartridges fail to offer. Where cheaper 78 cartridge/stylus combinations may sound closed down in the treble region, the RS78 shows that the fault is not always on the records, but in the playback equipment. It’s true that having custom, truncated styli tailored to the myriad groove sized encountered throughout the 78 era will yield the optimum results. But, the RS78 did a fine job on all of the records I auditioned.

Vertically cut discs can present unique problems. Pathé discs have a wide and rather shallow groove have a wide and rather shallow groove, and are notorious for being difficult records to track. The Pathé discs I tried with the RS78 played without problems, but anyone attempting to play these records should pay careful attention to tonearm adjustments. Skipping can often be corrected with careful anti-skate adjustment. Cheap tonearms and cartridges often fall flat with vertically cut Pathé discs. Owl made a special 3.7 mil glass stylus for Edison Diamond Discs (so-named because Edison’s phonographs had a diamond stylus in a floating reproducer to minimize record wear). But, I’ve found that a stock 3.0 mil conical stylus usually works well with these discs, and the RS78 lived up to expectations. The clean treble region of the Sumiko cartridge with RS78 had no difficulty revealing the superiority of Edison’s recording process compared to those of his competitors.

Shellac-based 78 rpm records are often noisy, and much of that noise is caused by the abrasive fillers that were necessary in order to ensure that the record wore the heavy steel “needles” rather than vice versa. The Victor Talking Machine Company’s formula for its record compound in the 1920s was 75% abrasive filler, an equal mix of powdered Pennsylvania slate and Indiana limestone [3]. Shellac was the binder that held it all together, and was only 13.6% of the compound. Fortunately, the metal parts that were used to press shellac records often survive in record company vaults. When they’re in good condition, they can be used to press vinyl records that are far quieter than the original pressings. I have many in my collection and used several in my evaluation of the RS78. The RS78 did an excellent job with these pressings, easily revealing their superiority in overall sound and lower noise, to original shellac pressings of the same recordings.

Collectors are often faced with the difficulties of tracking warped shellac records. I have a couple of badly warped 78 pressings that I keep on hand, to test the ability of tonearms and cartridges to deal these problems. Playback of a warped 78 will usually fail for one of two reasons. First, the warp can throw the arm upward causing the stylus to lose contact with the record groove. This is not the fault of the cartridge or stylus. The inertia of the tonearm causes the arm to continue in the direction it was sent. The Jelco SA-750 arms have fluid damping in the pivot, which helps, but there are limits on to the amount of damping fluid that can be used without compromising the playback of non-warped records. Second, the cartridge will bottom out when the high side of the warp hits the cartridge body — 78 rpm cartridges with a short stylus cantilever are prone to the second problem.

I tried one of my worst warp cases on the RS78 tracking at 5.5 grams, the manufacturer’s upper limit. The stylus lost contact with the record groove once every revolution. As an experiment, I temporarily increased the tracking force to 7 grams. This time, the record played without problems. I don’t recommend exceeding the recommended tracking force, but I wanted to see if the stylus cantilever was long enough to prevent the cartridge from bottoming out. The RS78 passed this test without problems. After this test, I promptly lowered the tracking force to the nominal 5.0 grams. Readers interested purchasing a turntable for 78 rpm playback should visit the web sites of Esoteric Sound, KAB Electro-Acoustics and Nauck’s Vintage Records. A fine entry-level 78 turntable table is the Audio Technica AT-LP140XP. More expensive models are also carried by these dealers.

LP Performance

The editor of audioXpress asked me to tackle this review because of my long-time interest in the playback of vintage records. But, the capabilities of the Olympia and Wellfleet cartridges playing modern stereophonic recordings will be the main reason most music lovers purchase these cartridges. I’ve included a short list of some of my favorite reference LPs. These records reflect a variety of stereophonic recording techniques, from fairly simple to heavily multi-microphone techniques.

David Hancock used four spaced Figure-8 ribbon microphones — a simple but unorthodox approach — on the Dallas recording of the Sergei Rachmaninoff Symphonic Dances, whereas Deutsche Grammophon used a forest of microphones on the Boston recording of Gustav Holst’s The Planets conducted by William Steinberg. Engineer Lewis Layton used three space omni-directional microphones, with a small number of judiciously placed accent mikes, on the RCA Victor Living Stereo recordings with Fritz Reiner and Charles Munch. Decca’s legendary engineer Kenneth Wilkinson used the three-microphone Decca Tree as his main pickup with spot miking that was tastefully accomplished. Articles I wrote some time ago on the Rachmaninoff recording, and stereo microphone techniques in general, provide additional information [4, 5].

A good vinyl playback system should reveal the differences in engineering on these recordings, and the Olympia did an admirable job. Decca’s secret was its ability to use accent microphones while still preserving the perspective of the main “tree” pickup, and maintaining a sense of depth on the accented sections of the orchestra. Deutsche Grammophon’s approach sound much more like the entire soundstage is manufactured rather than natural. RCA Victor Living Stereo recordings reflect Layton’s own skill at maintain a realistic soundstage, albeit with a very different main pickup. David Hancock’s Rachmaninoff LP was made in a very dry venue, but is notable for dynamic, realism of individual instrumental timbres, and a natural soundstage.

The Olympia had no problem revealing the essential qualities of each of these recordings. It gives a realistic hall ambience, and reveals the differences between ambience captured naturally by the main pickup, and ambience created by placing extra microphones out in the hall (Decca and RCA Victor vs. Deutsche Grammophon). The dryness of the Rachmaninoff is a striking contrast to the other venues in which these recordings were made, but the ribbon microphones favored by Hancock have a uniquely rich, full-bodied sonic character that is unlike any condenser microphone used in the other recordings. The differences were ably revealed by the Olympia. The Olympia is surprisingly detailed and articulate for a cartridge in this price range, with a smooth treble region that should provide many hours of musically-satisfying listening.

The Wellfleet takes its virtues of the Olympia several steps further. High-frequency extension and detail are greatly improved, sound staging is more three-dimensional, with the most noticeable improvement being in depth. Bass is better defined and extended. The Wellfleet is a very refined cartridge that reveals subtleties in a recording – and subtle differences between recordings—that less expensive cartridges can’t be expected to match.

There’s a credible sense of high-frequency air that, while not the equal of my Denon DL-103R moving-coil cartridge, gives you a taste without the expense of an outboard step-up device, or the noise that can be introduced by the extra gain required by moving-coil cartridges. Moving from the Olympia to the Wellfleet takes you from affordable high-end vinyl playback to performance that approaches the best that can be achieved with moving-magnet design. Like the Olympia, the Wellfleet provides natural, non-fatiguing sound that should be good for the long haul.

Since my retirement from the Crane School of Music at SUNY Potsdam I’ve been doing volunteer work in its recording archive, transferring vintage Crane performances to digital. Next fall I will begin a series of transfers from some very well-recorded LPs made in the mid-to-late 1960s. I’ve decided to use the Wellfleet for this important project.

Conclusion

Although any of the four cartridges in this series can be converted to 78 rpm playback by removal of the LP stylus and insertion of the RS78, the swap can be a bit tricky. The plastic stylus mount has smooth and rather narrow sides, making a solid grip difficult. I found that the safest way to swap styli is to remove the headshell and place it upside down on a table. By grasping the back edges of the stylus mount, I was able to safely pull the stylus out of the cartridge body. I wish Sumiko would consider selling the cartridge housing bundled with only the RS78 stylus, for those who don’t need an LP stylus.

If you plan to use one of these cartridges for both 78 and LP playback, you might consider purchasing the low-priced Rainier, mounting it in a dedicated headshell for 78s only. The Rainier sells for only $149 (replacement cartridge $89), making it a very affordable solution for a dedicated 78 cartridge, free of the risks and hassles of stylus swaps.

The Sumiko Olympia and Wellfleet cartridges are excellent cartridges in their respective price ranges. The Olympia makes is a cost-effective way to enter the world of high-end vinyl playback, while the Wellfleet offers performance that puts in near the upper end of moving-magnet designs. Fitted with an RS78 stylus, any cartridge in this series will provide fine performance on 78 rpm discs. aX

Sumiko Olympia Phono Cartridge

Wellfleet Phono Cartridge

RS78 78 rpm Stylus

Sumiko

63 95th Ave. N

Maple Grove MN 55369

510-843-4500

sumikophonocartridges.co

service@sumikoaudio.net

Olympia Phono Cartridge: $199.00

Olympia Stylus: $119.00

Wellfleet Phono Cartridge: $449.99

Wellfleet Stylus: $339.00

RS78 Stylus: $129.99

63 95th Ave. N

Maple Grove MN 55369

510-843-4500

sumikophonocartridges.co

service@sumikoaudio.net

Olympia Phono Cartridge: $199.00

Olympia Stylus: $119.00

Wellfleet Phono Cartridge: $449.99

Wellfleet Stylus: $339.00

RS78 Stylus: $129.99

Recordings Used for Evaluation (Selective List)

78 rpm Original Shellac Pressings

Buzzi-Peccia: “Lolita” (Spanish Serenade). Enrico Caruso, tenor. Victor 88120, Recorded in 1908, 76.6 rpm. (Acoustical recording)

Chopin: Ballade in F-minor, Op. 52. Alfred Cortot, pianist. HMV D.B. 1346, Recorded in 1929. 77.5 rpm. (Electrical recording).

Gounod: Roméo et Juliette—“Ah! leve-toi soleil.” Lucien Muratore, tenor. Pathé 64006B, Recorded in 1918, 73.5 rpm (Vertically cut; Acoustical recording).

Prokofiev: Classical Symphony in D, Op. 25. Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Serge Koussevitzky. RCA Victor set DM-1241, Recorded in 1947, 78.26 rpm (Electrical recording).

Wagner: Lohengrin—Prelude to Act I. Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Wilhelm Furtwängler. Polydor 95.408, Recorded in 1930, 78.26 rpm (Electrical recording).

Wagner: Rienzi—“Allmächt’ger Vater.” Jacques Urlus, tenor. Edison Diamond Disc 82269, Recorded in 1922, 77.0 rpm (Vertically cut; Acoustical recording).

Weber: Oberon—Overture. New York Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Willem Mengelberg. Victor 74766 & 74767, Recorded in 1922, 75.00 rpm (Acoustical recording).

78 rpm Vinyl Re-Pressings from Original Metal Matrices

Bach: Fantasia and Fugue in C-minor, BWV 537, arr. Elgar, Op. 86. Royal Albert Hall Orchestra conducted by Sir Edward Elgar. HMV Matrix Nos. CR 346-IIA (previously unpublished) & CR 347-1A. Repressing by Symposium, 1025, 75.0 rpm. (Electrical recording).

Chopin: Ballade in A-flat, Op. 47. Sergei Rachmaninoff, pianist. Victor Matrix Nos. CVE-32510-1 & 32511-1. Recorded in 1925. Vinyl pressing made for transfer to LP and CD releases, previously unpublished, 75.0 rpm. (Electrical recording).

Giordano: Andrea Cheniér—“Un di all’azzuro spazio.” Francesco Tamagno, tenor. Gramophone Monarch 052100, Recorded in 1904. Repressing by Historic Masters HM-FT7B. 73.0 rpm. (Acoustical recording).

Verdi: Aida—“Pur ti riveggo…Fuggiam gli ardori inospiti.” Melanie Kurt, soprano & Jacques Urlus, tenor (sung in German). Grammophon 2138c & 2139c. Recorded in 1911. Repressing by Historic Masters. 80.0 rpm (Acoustical recording).

Stereo LP Records

Dukas: The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (in the album The French Touch). Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Charles Munch. RCA Victor Living stereo LSC-2292. Recorded in 1957, Orchestra Hall, Chicago, IL. Recording Engineer: Lewis Layton, Producer: Richard Mohr. Reissue by Analogue Productions.

Holst: The Planets. Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by William Steinberg. Deutsche Grammophon 2530 102 (Germany). Recorded in 1970, Symphony Hall, Boston, MA. Balance Engineer: Günter Hermanns, Producers: Karl Faust and Thomas Mowrey.

Rachmaninoff: Symphonic Dances, Op. 45. Dallas Symphony Orchestra conducted by Donald Johanos. Turnabout TV 34145S. Recorded in 1967, McFarlin Auditorium, Dallas, TX. Recording Engineer: David Hancock, Producer: Thomas Mowrey. 45 rpm reissue by Analogue Productions (two 12” records).

Rimsky-Korsakoff: Scheherazade, Op. 35. Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Fritz Reiner. RCA Victor Living Stereo LSC-2446. Recorded in 1960, Orchestra Hall, Chicago, IL. Recording Engineer: Lewis Layton, Producer: Richard Mohr. Reissue by Analogue Productions.

Wagner: Die Walküre. Jon Vickers, David Ward, Gré Brouwenstein, George London, Birgit Nilsson, Rita Gorr; London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Erich Leinsdorf. Decca (British) 7BB 125-9 (5 records). Recorded in 1961, Walthamstow Town Hall, London, UK. Recording Engineer: Kenneth Wilkinson, Producer: Eric Smith.

Buzzi-Peccia: “Lolita” (Spanish Serenade). Enrico Caruso, tenor. Victor 88120, Recorded in 1908, 76.6 rpm. (Acoustical recording)

Chopin: Ballade in F-minor, Op. 52. Alfred Cortot, pianist. HMV D.B. 1346, Recorded in 1929. 77.5 rpm. (Electrical recording).

Gounod: Roméo et Juliette—“Ah! leve-toi soleil.” Lucien Muratore, tenor. Pathé 64006B, Recorded in 1918, 73.5 rpm (Vertically cut; Acoustical recording).

Prokofiev: Classical Symphony in D, Op. 25. Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Serge Koussevitzky. RCA Victor set DM-1241, Recorded in 1947, 78.26 rpm (Electrical recording).

Wagner: Lohengrin—Prelude to Act I. Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Wilhelm Furtwängler. Polydor 95.408, Recorded in 1930, 78.26 rpm (Electrical recording).

Wagner: Rienzi—“Allmächt’ger Vater.” Jacques Urlus, tenor. Edison Diamond Disc 82269, Recorded in 1922, 77.0 rpm (Vertically cut; Acoustical recording).

Weber: Oberon—Overture. New York Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Willem Mengelberg. Victor 74766 & 74767, Recorded in 1922, 75.00 rpm (Acoustical recording).

78 rpm Vinyl Re-Pressings from Original Metal Matrices

Bach: Fantasia and Fugue in C-minor, BWV 537, arr. Elgar, Op. 86. Royal Albert Hall Orchestra conducted by Sir Edward Elgar. HMV Matrix Nos. CR 346-IIA (previously unpublished) & CR 347-1A. Repressing by Symposium, 1025, 75.0 rpm. (Electrical recording).

Chopin: Ballade in A-flat, Op. 47. Sergei Rachmaninoff, pianist. Victor Matrix Nos. CVE-32510-1 & 32511-1. Recorded in 1925. Vinyl pressing made for transfer to LP and CD releases, previously unpublished, 75.0 rpm. (Electrical recording).

Giordano: Andrea Cheniér—“Un di all’azzuro spazio.” Francesco Tamagno, tenor. Gramophone Monarch 052100, Recorded in 1904. Repressing by Historic Masters HM-FT7B. 73.0 rpm. (Acoustical recording).

Verdi: Aida—“Pur ti riveggo…Fuggiam gli ardori inospiti.” Melanie Kurt, soprano & Jacques Urlus, tenor (sung in German). Grammophon 2138c & 2139c. Recorded in 1911. Repressing by Historic Masters. 80.0 rpm (Acoustical recording).

Stereo LP Records

Dukas: The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (in the album The French Touch). Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Charles Munch. RCA Victor Living stereo LSC-2292. Recorded in 1957, Orchestra Hall, Chicago, IL. Recording Engineer: Lewis Layton, Producer: Richard Mohr. Reissue by Analogue Productions.

Holst: The Planets. Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by William Steinberg. Deutsche Grammophon 2530 102 (Germany). Recorded in 1970, Symphony Hall, Boston, MA. Balance Engineer: Günter Hermanns, Producers: Karl Faust and Thomas Mowrey.

Rachmaninoff: Symphonic Dances, Op. 45. Dallas Symphony Orchestra conducted by Donald Johanos. Turnabout TV 34145S. Recorded in 1967, McFarlin Auditorium, Dallas, TX. Recording Engineer: David Hancock, Producer: Thomas Mowrey. 45 rpm reissue by Analogue Productions (two 12” records).

Rimsky-Korsakoff: Scheherazade, Op. 35. Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Fritz Reiner. RCA Victor Living Stereo LSC-2446. Recorded in 1960, Orchestra Hall, Chicago, IL. Recording Engineer: Lewis Layton, Producer: Richard Mohr. Reissue by Analogue Productions.

Wagner: Die Walküre. Jon Vickers, David Ward, Gré Brouwenstein, George London, Birgit Nilsson, Rita Gorr; London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Erich Leinsdorf. Decca (British) 7BB 125-9 (5 records). Recorded in 1961, Walthamstow Town Hall, London, UK. Recording Engineer: Kenneth Wilkinson, Producer: Eric Smith.

References

[1] Galo, Gary. “An Archival Phono Preamp,” Linear Audio, Volume 5, 2012, pp. 77-104.

[2] J. P. Maxfield and H. C. Harrison. “Methods of High Quality Recording and Reproducing of Music and Speech based on Telephone Research,” Bell System Technical Journal, Volume 5, No. 3, July 1926, pp 493-523. Available from the Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/bstj5-3-493.

[3] W. R. Isom, “Record Materials, Part II: The Evolution of the Disc Talking Machine,” Journal of the Audio Engineering Society, Special Centennial Issue, Volume 25, No. 11, October/November 1977, p. 719.

[4] G. Galo, “The Legendary Rachmaninoff Symphonic Dances,” audioXpress, December 2012, pp. 24-28.

[5] G. Galo, “Stereophonic Recording: What do Listeners Prefer?” audioXpress, April 2014, pp. 22-28.

Resources

Audio Technica,

www.audio-technica.com/en-us/turntables/type/direct-drive/at-lp140xp

Esoteric Sound, www.esotericsound.com

KAB Electro Acoustics, www.kabusa.com

Nauck’s Vintage Records https://78rpm.com/collections/audio-gear

Sumiko Audio | www.sumikophonocartridges.com

About the Author

About the AuthorGary Galo retired in 2014 after 38 years as Audio Engineer at The Crane School of Music, SUNY at Potsdam, NY. Since then he has worked as a volunteer in the Crane Recording Archive, transferring vintage Crane recordings to digital. He is the author of over 300 articles and reviews in over a dozen publications, and has been writing for audioXpress and its predecessors since the early 1980s. Gary is a long-time active member of the Association for Recorded Sound Collections, a frequent presenter at ARSC conferences and the author of numerous articles and reviews in the ARSC Journal. He is a member of the Boston Audio Society and a Life Member of the Audio Engineering Society.

This article was originally published in audioXpress, October 2022.