Enter The (Tiny) Dragon

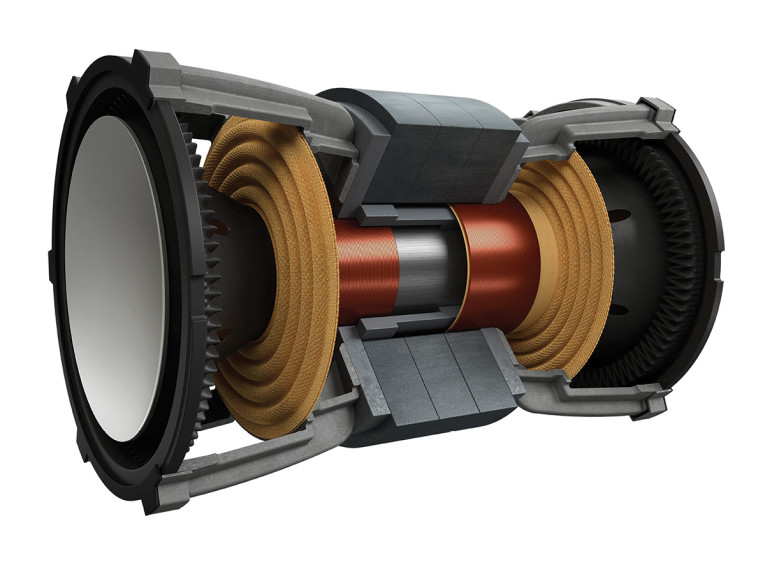

Herald the KC62 microsub, which is shorthand for KEF Compact 6” x 2. Unlike most of the competition, the KC62 is not ported. Also unlike the competition, the KC62 has dual drivers. Actually, there is very little that the KC62 has in common with other small subwoofers. This little cube goes one better than the traditional force cancelling, opposing woofer configuration. To save space, and my goodness does it ever, designer Jack Starkey and his team at KEF designed “Uni-Core,” a novel coaxial voice coil approach (Photo 1). Coaxial loudspeakers are not unusual and, when designed right, can provide point–source imaging. KEF is known for its widely respected and refined coaxial designs. Usually, those quotidian coax driver designs are a tweeter surrounded by a mid-woofer, and are both configured to launch their sound in the same direction.

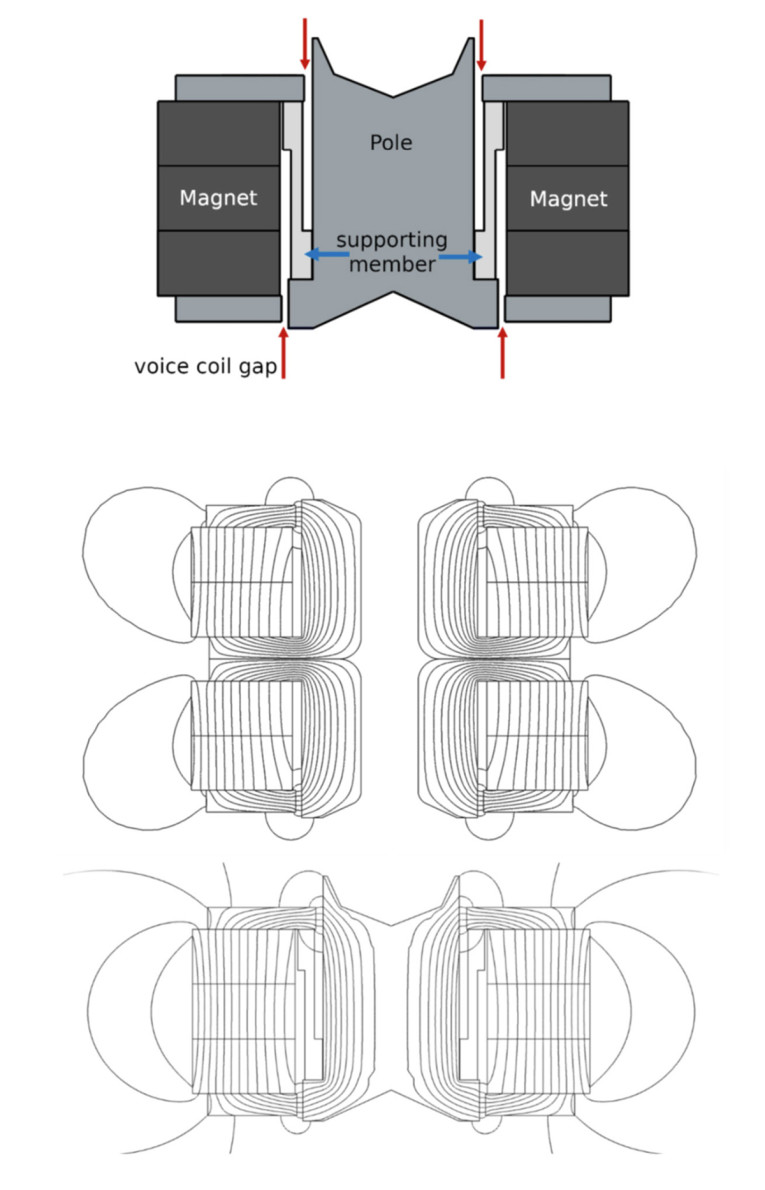

In an attempt to game the immutable pas de trois of loudspeaker physics — cabinet volume plus low-frequency extension and efficiency — Starkey fused two force-cancelling, opposing low-frequency drivers by devising a common motor. The two voice coils each have different diameters, allowing one to be nestled concentrically within the other. This arrangement allows the voice coils to “…travel within their own gap without colliding.” Two drivers mean more surface area, while the Uni-Core arrangement saves space. Utilizing the same constituents as 2019’s larger and more conventional KF92 sub, the cones are of a laminated aluminum-over-paper construction.

The KC62 is an active, acoustic suspension design for outstanding transient behavior and flatter frequency response. However, a sealed cabinet incurs higher internal pressure and higher temperatures for both the voice coils and the two 500W Class-D amplifiers. To address those obstacles, an extruded aluminum enclosure was chosen, clad in either an all–black or all–white finish. A metal housing plus 1000W of power amplification allows the product to cleanly play louder without resonant coloration, and go a good 10Hz to 25Hz lower than other micro subs. The little devil is spec’d at 11Hz to 200Hz ±3dB. You may ask, just how small is a “micro” sub (Photo 2)? In this case, we are talking a munchkin–sized 246mm × 256mm × 248mm (9.68” × 10.07” × 9.76”). What it lacks in size is made up for in bulk, weighing in at a surprisingly hefty 14kg (30.9lb). Hiding inside that little fatty is one KEF custom power supply for the electronics, supplying low voltage bits such as the CPU and DSP, and another PSU for the amps themselves.

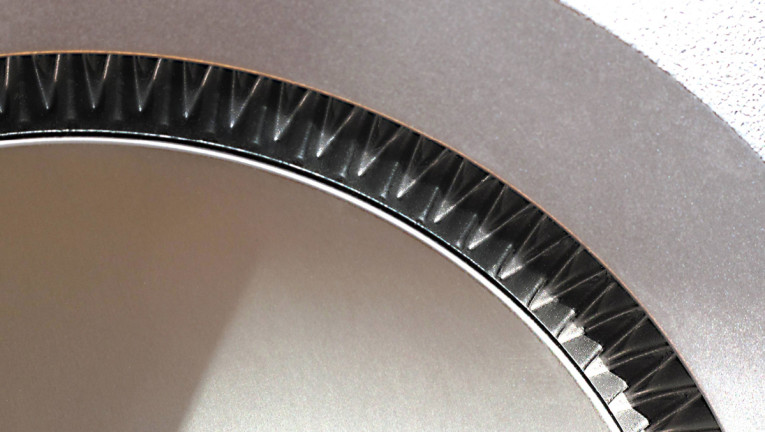

Not only is the design active, it’s largely digital, with DSP for flat and extended response, while offering a range of boundary compensation and other accommodations for placement and environment. Given the design, one would expect long throw drivers, and KEF addresses that challenge with a novel folded surround rather than the more easily distorted half-roll approach. Its patented “P-Flex” surround is a pressure-resistant, pleated design (Photo 3).

According to KEF, the shape is optimized “…to resist the deformation caused by the changing internal air pressure of the cabinet, whilst allowing extended, linear movement” of the drivers (Figure 1). As an added extra, the signal processing incorporates “Smart Distortion Control Technology” (SDCT), a hybrid system combining DSP pre-correction with indirect cone motion sensing and feedback.

A Different Stripe

Although the KC62 has a subwoofer mode along with a Low Frequency Effects (LFE) mode, most folks think of subwoofers—when they think of them at all—as the LFE part of a home-theater setup. That is a decidedly old school slant right there, y’all. It’s true that subs entered the common lexicon through consumer acceptance of Dolby Surround and its 5.1 setups in homes, but modern subwoofers are far more capable than those one note wonders of the 1980s. Granted, the subs included in home-theaters-in-a-box, the kind you find for $200 to $600 at your local big box store, are only good at vaguely approximating explosions and the like. They are not meant for or capable of providing satisfying musical enhancement.

The KC62 is a whole other animal. It provides a visually inconspicuous, aurally subtle but essential foundation for musical enjoyment. It unobtrusively “pressurizes” the room, filling in an octave-and-a-half that you may not know you’re missing. During the review period, I only had stand mounters in the house and, in all cases, I found the midrange felt more realistic and complete when I added that tiny bit of extremely low-frequency energy.

Without the sub, the music was pointier, subjectively more mid–dominant regardless of which speaker I was using at the time. Bringing the sub into the equation made for a more enveloping and complete sense of pretty much everything I listened to. The KC62 provides a solid foundation on which to build a convincing sonic portrait.

Obviously, some material has little or no bottom two octaves, but that’s the exception. That said, a few notes of caution are indicated…If you like it really loud, the KC62 isn’t a good fit. When KEF makes a Uni-Core big sister, then that would be the model to check out. In the meantime, the beefier and more traditional KF92 (“maximum output,” 110dB versus the KC62’s 105dB) might be a better choice. If you have open baffle main speakers, likewise the KC62 is most definitely not the droid you’re looking for. Open baffle speakers want open baffle subs. Madisound has a nice Linkwitz-style, open baffle Z sub kit that’s inexpensive and looks easy to build.

True Confessions

Now I must confess to a totally un-audiophile indulgence. With friends over to our house for entertaining, I routinely dial up a moderate loudness curve that boosts both top and bottom while aggressively high-pass filtering below 20Hz to prevent excess excursion. This allows us to easily hold a conversation while still blanketing the house in background music. I found that goosing the sub gain past its “normal” amplitude setting gives the loudness a substantial increase in impact and fun factor without interfering with speech intelligibility. Since the rotary controls on the KC62 are detented, it’s easy to return thing to “normal” after fiddling.

Control Freak

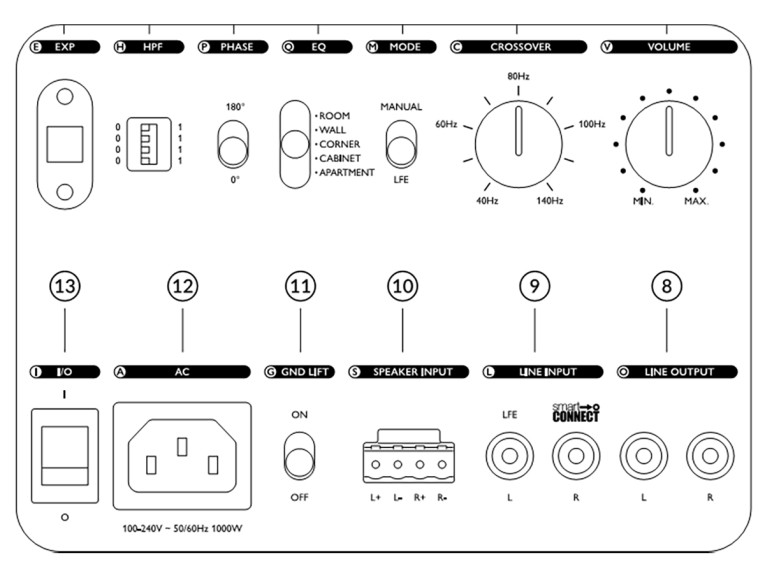

Let’s talk about those controls… There’s no plethora of slightly discombobulating knobs and switches as you’d find on the typical plate amp-based sub of yore. The controls that KEF provides are quite straightforward — the classic crossover frequency and volume knobs, along with a five position EQ switch for room gain compensation. A polarity invert slide switch, suspiciously marked “PHASE,” and a Mode switch round out the grouping (Photo 4).

When I asked Sharkey about an alternative POLARITY label, he corrected me by saying that, since they only switch phase 180°, “…then yes in a sense it is a polarity switch but that wouldn’t be the proper way to describe it: It’s a phase adjustment.” Mode is a two-position slider — the MANUAL setting is for use with a stereo line level input, while the LFE mode is for when the KC62 is being fed by the mono LFE output of the A/V Receiver (AVR). When using an upstream device, like an AVR, you can set the crossover via the LFE channel on your amp/processor, sending the desired frequencies to the subwoofer. When using an LFE from the AVR, setting the sub to LFE defeats the internal subwoofer crossover in favor of the AVR’s crossover. If you are not using an upstream device to set the crossover, then you’d set the switch to Manual, which engages the subwoofer’s own on-board crossover. Being able to manually control it prevents contention problems between the on-board crossover and the amp/processor’s own crossover.

All processing is performed in the digital domain, and the EQ settings inform the embedded DSP. Choices are Room, Wall, Corner, Cabinet, and Apartment. The first three are self-explanatory, with each of the settings shelving the low frequencies differently. Wall is somewhat less steep, Corner is a little steeper, “…Cabinet is very steep, while Apartment is kind of shallow then gets very steep below around 50Hz” to attenuate structural-borne vibration traveling through walls and floors. Sharkey mentioned that all of the EQ settings, “…start around 200Hz or lower and then vary according to the setting to compensate for Boundary Gain.”

I tested the KC62 in our living room, which serves the dual purpose of listening room as well. It is a decidedly typical space, not ideal for high-fidelity pursuits but that’s what many folks are faced with. Due to furniture placement, I had only four locations that would work, and three of them resulted in extreme and intolerable room node excitation, with huge dips and nulls as one moved about the space. The fourth position turned out to be quite ideal. Without applying any active room acoustics compensation, my favorite being Dirac, the low end was fairly consistent regardless of seating position.

My test configuration included the $200 KW1 wireless transmitter kit. This optional add-on is essential for optimal placement as it frees you from interconnect length constraints. It operates in the 5GHz radio band, delivering audio at up to 24-bit/48kHz. The KW1 works with five different KEF sub models, and two $100 KW1 receivers (also sold separately) accommodate two simultaneous subs for more even low-frequency coverage. I fed the USB-powered transmitter from Parasound’s JC 5 convenient parallel RCA aux outs, while the easily installed miniature receiver plugged directly into a pin grid block on the KC62’s control panel. The receiver also sports an LED that acts as a reassuring idiot light when properly paired.

To set the controls, I decided to use what most consumers have on hand — their ears and a phone. I started by selecting the appropriate boundary compensation, and twisting the gain knob and crossover frequency to minimum. After that, it was a simple matter of playing some test material‡ while progressively increasing the crossover frequency until I closed the gap between speakers and sub. For objective verification, I employed Fabien Lefebvre’s outstanding SPLnFFT measurement app for iOS. Since the KC62 is DSP-driven, it wasn’t ideal to turn it off and on to bypass the sub, so I visually made a mental note of the volume knob position, and dialed the gain down then back to the reference setting to bring the sub in or out.

After about 15 minutes of futzing around, I arrived at a very pleasing group of parameters. The sub was not obvious unto itself, but when disabled suddenly produced a major letdown. “Where’d that bedrock go?” Over the course of a few hours of listening with a wide variety of music, I arrived at a default setting that I could easily veer off from when I wanted dance floor low end, and instantly arrive right back at my reference when the booty shaking had been satisfied.

I can find little fault in the KC62. My time with the product was illuminating in a variety of ways. A well-behaved sub, the KC62 is certainly that, contributes the appealing low-frequency underpinning that most speakers cannot provide or that one cannot afford. It places the midrange in proper perspective, psychoacoustically completing what one doesn’t know one needs until it’s missing. When properly set up, a sub will not call attention to itself. Instead, it plays the vital role of aural fundament, on which your speakers invisibly rest.

Despite its size, the KC62 handily competes with units both larger and more costly, failing only when stomach-churning levels of bottom octave are needed. You pay more for performance, and this little dragon delivers. Speaking of size, the KC62’s extra-small form factor and curvaceous good looks combine to provide a very high spousal approval factor.

The team at KEF have followed its award-winning LS50 Meta with the perfect low-frequency complement. (Read my audioXpress June 2021 review) Together is better. The reasonably priced stand mounters and sub occupy a tiny amount of floor space, yet dish out heaping oodles of wonderfully high fidelity sound. If you’re considering a quality sub purchase, I suggest you try to include some time with a KC62 in your schedule. aX

Author’s Note: ‡ I used the AudioTest application from Katsura Shareware, setting up a 10Hz to 80Hz slow sweep.

About the Author

About the AuthorOliver A. Masciarotte has spent more than 40 years immersed in the tech space, working on manufacturing, marketing, and product development for many pro and CE audio manufacturers including dbx, a/d/s, Lexicon, Sonic Solutions, and Minnetonka Audio. His client roster is as diverse as Apple, Harper Collins, NASA Johnson, NPR, and Universal. His writings include a book covering file-based music for the home and more than 100 articles for sundry trade publications. A member of the Audio Engineering Society (AES), Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers (SMPTE), Project Management Institute (PMI), and Digital Cinema Society (DCS), he is currently co–founder and CMO of MAAT Inc., a digital audio software manufacturer.

Inside the Mind of Jack Sharkey, Senior Technical Engineer at GP Acoustics International

Inside the Mind of Jack Sharkey, Senior Technical Engineer at GP Acoustics InternationalOliver Masciarotte: What was the design brief? To create the world’s heaviest sub in the world’s smallest footprint?

Jach Sharkey: The world’s “smallest footprint” is spot-on, and the necessary result of doing that the right way was the weight!

Masciarotte: What were the design challenges and how were they overcome?

Sharkey: Obviously the biggest design challenge was to create an enclosure for a large subwoofer in a very small package. The challenge was to create a “small” subwoofer that didn’t compromise on performance but was able to compete with much larger subwoofers in a super consumer-friendly package for the way people are setting up their listening spaces today.

Masciarotte: As with the LS50 Meta, you chose a novel approach to the problem; the concentric voice coils. Why the expense embodied in extra R&D, tooling, extended lead time, etc., when you could have gone the “easy” route of low profile, opposing drivers?

Sharkey: Since 1961 we’ve been about engineering solutions instead of just making something that might enhance performance. We think outside of the current tech box and seek ways to solve problems without regard for the cost or time involved. Blade and KC62 are prime examples. Using opposing drivers would not have saved as much space as we wanted as the concentric voice coils did, but doing concentric voice coils that perform at a very high level required a lot of other design and research efforts. It’s the typical design journey—one thing leads to another, and there are tons of compromises along the way; the key is picking and choosing what compromises to live with. The weight of the KC62 is a perfect example of that: In order to perform at the level we wanted KC62 to perform at, the box was going to be necessarily heavy. We’ve never been about doing things the “easy” way—you can’t really innovate and cut corners at the same time. The extended lead time is really just a result of the pandemic and all of the surrounding supply chain issues that all of us are confronting at the moment. Under normal circumstances KC62 would have been readily available and shipping without delay.

Masciarotte: Tell me about the enclosure…why aluminum instead of resin/composite or something else?

Sharkey: In a cabinet housing this powerful of a system, there would be serious (pressure) equalization forces on the cabinet walls. This would cause intolerable vibrations that would color the sound as well as force us to put in so much bracing that the internal air volume would be decreased, hence decreasing the low-frequency response of the subwoofer (compromised internal volume leads to decreased performance). To overcome this, an extruded aluminum cabinet was used. Aluminum has a higher elasticity than wood for a given thickness, so the use of a thinner wall was possible, allowing for a larger internal volume. Curved surfaces are also significantly more rigid than flat surfaces. The aluminum extrusion is a curved shell forming a monocoque or structural skin…This structure ensures there are no stress points, which might compromise cabinet integrity causing distortion. We could therefore reduce internal bracing and not have to worry about the strength of the enclosure when responding to the internal air pressure force.

Masciarotte: Is this product manufactured in China to your specifications?

Sharkey: We are a Tier One manufacturer, which means we control every aspect of production from concept to packaging as the product leaves the factory. We have a totally owned, and internally designed by our industrial and engineering teams, factory in Huizhou China. But as a Tier One manufacturer, we don’t use contract labor, contract factories, sub-assembly factories, or any of the like — it’s all done by our employees to our standards, which is a bit of a rarity in our industry today.

Masciarotte: Why did you go the “old fashioned” way of manual controls?

Sharkey: We did both, so the end-user has a choice on how to control and operate the sub. You can either use the manual controls or if you are using the KEF Connect app with an LS50 Wireless II for example, most of the subwoofer functions can be controlled via the app. As far as embedded software and DSP for the sub, because of the above and how subs are generally thought of for high-end audio, we opt more for the “straight-wire-with-gain” mindset—less is ultimately more when it comes to sonic fidelity.

KEF KC62 Subwoofer: The Measurements

The KEF KC62 subwoofer was measured at Warkwyn’s facility using the Klippel Near Field Scanning system (NFS) in combination with Klippel’s In-Situ Compensation module (ISC) to examine distortion, compression, and frequency response curves in the different “Mode” settings.

By Kent Peterson

The KEF KC62 subwoofer was measured at Warkwyn’s facility using the Klippel Near Field Scanning system (NFS). The NFS delivers a 360° acoustical radiation balloon allowing for an examination of the radiation pattern, on/off-axis frequency response at any angle or distance. Of course, for this examination, it would be rather ridiculous to examine subwoofer radiation balloons as they are mainly omni-directional, and we all know what those balloons would look like. So, we also employed Klippel’s In-Situ Compensation module (ISC) to examine distortion and compression of the KC62. The ISC, in conjunction with the NFS software, allows a user to make certain measurements including CTA-2010A and B after using Klippel’s signature room removal abilities.

For the measurements of the KC62, we used a calibrated ACO Pacific free-field microphone with the 4048 pre-amp and a 7052E capsule (Photo 1). Measurement points around the speaker totaled 2000 and were processed with a resolution of 18 points per octave and from 20Hz to 20kHz. The length of the stimulus was 0.68 seconds with an averaging of 4.

Frequency Response and Various Settings

The KC62 has some great flexibility incorporated into its amp section, which enables users to tailor the sub to various listening locations in their homes. These are “Room/Wall/Corner/Cabinet/Apartment” settings that apply various filter options, as well as a 4-dip switch option, which adjusts various high-pass filters from 40Hz through 100Hz.

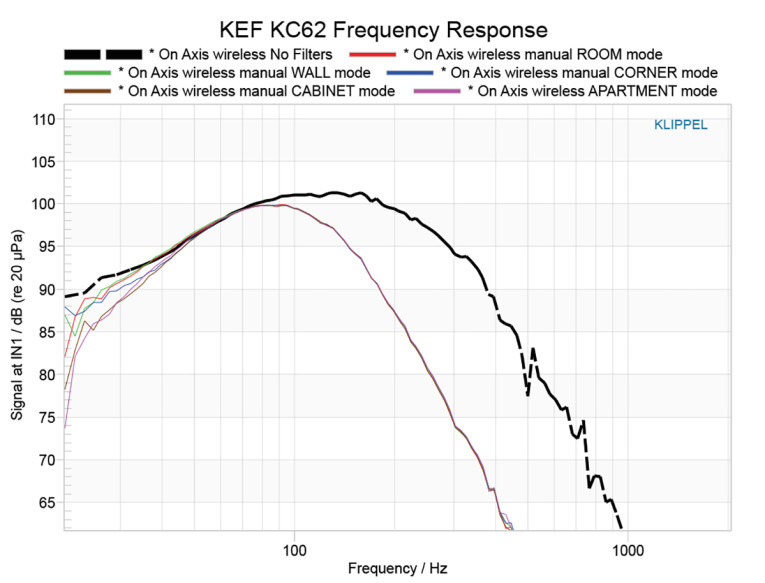

A detented, rotational crossover knob that adjusts from 40Hz to 140Hz. For the purposes of our analysis, all dip switches were set to 0/bypass, the mode set to “Manual” and the crossover was rotated completely to the 140Hz setting to allow the sub to play its complete range. Volume for the system was set at the maximum position. As shown in later portions of this analysis, various voltages were then injected into the sub to analyze system compression (Figure 1).

Figure 2 illustrates the frequency response of the KC62 while bypassing all filter options, with the high-pass filters set to its maximum (140Hz), and then for each of the EQ setting available for room optimization.

Leaving you to your own devices (or by using the LFE mode), the system response is centered around 150Hz and extends up to 400Hz and as low as 20Hz, 10dB down (we did not measure below 20Hz as output at that point was nominal). Inserting your own crossover filter in this mode may allow the user greater flexibility by shifting the crossover point higher and delivering greater output between 100Hz and 200Hz.

With the various EQ settings engaged, the center frequency is lowered to between 80/90Hz and applies a low-pass filter with a 10dB down point at 180Hz. Where the EQ seems most effective is lower in frequency, between 20Hz and 50Hz. Of these modes, the Wall mode and the Room mode exhibited the greatest output down to 20Hz, with the Room mode exhibiting a small 1dB bump at 22Hz.

The Apartment mode and the Cabinet mode have the greatest amount of attenuation down to 20Hz, with a 10dB difference between those and Room and Wall modes. Either way, these differences are very low in frequency and 5dB to 10dB lower than no filtering whatsoever. Though probably effective in keeping the drink coasters from rattling in your neighbor’s apartment, they are subtle changes to be sure.

Compression and Maximum Output

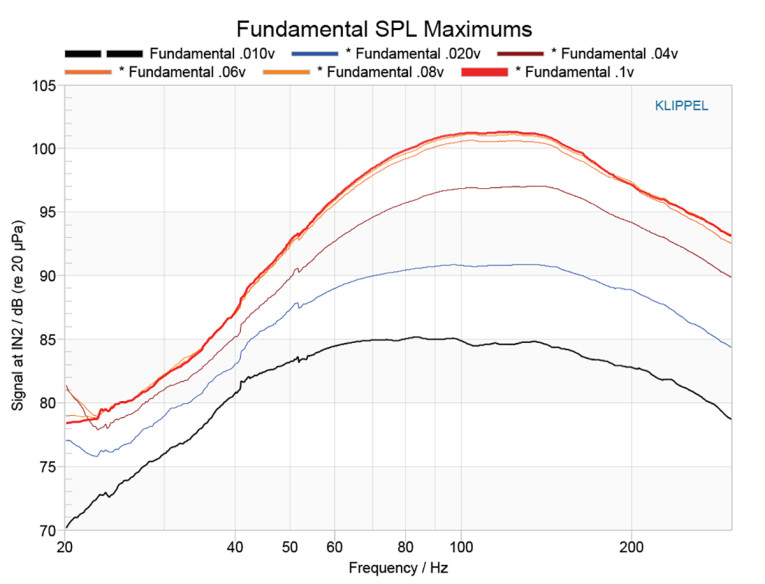

In pondering what measurements would be most beneficial to the casual listener and reader, maximum output is certainly one of them, especially when examining a subwoofer that has little to discuss in terms of radiation pattern and very wide frequency response. First, we decided to examine when and where any DSP compression would begin to flatten frequency response and curtail SPL.

Beginning with 0.01V, we swept the sub while increasing voltage by 0.01, and then in subsequent steps of 0.02 until output had maxed, and no further output could be had at 0.1V. Keep in mind that we tested a powered system here with the volume knob positioned at maximum. So, it’s important to note that the voltage levels are ratios and, depending on where your volume level is, your voltages are going to vary radically if you are one of those people who want to set up a meter to monitor your sub input. The main take-away here is maximum decibel output and how that affects your frequency response. Your easiest measurement tools here are a good mic, a calibrated analyzer, and about 1 meter.

At 0.01V, there appears to be very little compression, however, even a small increase in voltage (0.01V) appears to engage compression below 50Hz. Subsequent steps to 0.1V only result in an increase of 6dB to 10dB in the lowest frequencies. Remembering our human association with the decibel; a 3dB change can be considered human threshold, a 6dB increase can be considered “clearly noticeable,” and a 10dB change a doubling (or halving) of apparent loudness. Turning up this sub to its maximum from 0.01V should result in an apparent doubling of output in the lowest frequencies until a point where compression limits max output at 80dB to 85dB (consideration of A-weighting here, which is valid, will make your lower frequencies measure far less over the lower spectrum of course).

Compression between 60Hz and 200Hz is less than that of the lower frequencies and results in a 6dB increase in output until 0.04V is reached. At 0.06V the real clampdown happens before capping at 0.1V, where no further output could be measured above 101dB and at 100Hz (Figure 3).

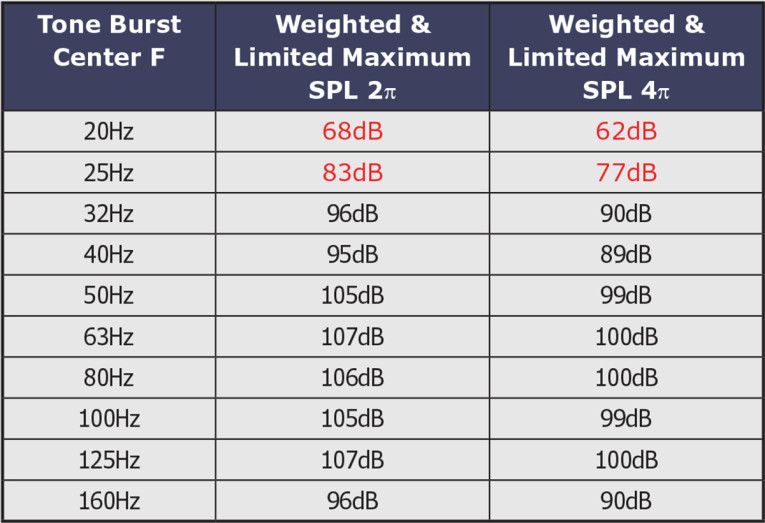

Tone Burst Measurement/CTA-2010B

Finally, a tone burst measurement was performed to quickly examine how the KC62 might fare against the current CTA-2010B standard. For reporting, we detailed the last decibel reading encountered before distortion failures are registered (Table 1). Center frequency reporting for 2010B is listed with corresponding decibel levels and for two scenarios; 4π (full space, or how we performed the measurements), and 2π (half space, which is more applicable to “real-world” conditions). However even with 2π measurements, your results may even be higher by a decibel or two due to placement near walls.

The values reported in Table 1 represent the last pressure level that “passed” the 20210B landmarks before distortion failures were encountered in each band. As per the red type, for the center frequencies of 20Hz and 25Hz, at no time during the tone burst measurement was there a result of “pass.” There just wasn’t enough acoustic output way down low to overcome the distortion values. Though to be completely fair, the chamber we used for this measurement is closer in the building to HVAC so it may be that the measurement this low in frequency is compromised by the noise floor. Nevertheless, the values listed in Table 1 very closely mimic our frequency response measurements and those of compression; in the lowest frequencies compression came on almost immediately, which is another factor for consideration. Finally, no voltages are listed here as we simply turned the volume all the way up as it is a powered sub.

Final Thoughts

I did have a chance to do some spot listening of the KC62 during the time I had to work with it. Though, sadly, not paired with the KEF LS50 Meta cabinets we examined a few months ago. But when I did have the chance to listen, I was very impressed with how they sit in a mix and am obviously impressed with the product line; well-thought-out and very well manufactured. Are they the loudest/lowest sub out there? No. But that’s not where I think this sub sits in the marketplace—it is a refined little subwoofer, made with quality materials and sophisticated engineering and will work great in your library, office, or living room and deliver just the oomph you might be missing. aX

This article was originally published in audioXpress, March 2022.

About the Author

About the AuthorKent Peterson is sneaking up on 30 years in the Pro Audio and Acoustics field. Having designed hundreds of audio systems for professional install and approximately 100 miles of noise walls, Peterson now spreads sawdust on employee “accidents” managing Warkwyn in Saint Paul, MN.